The World Was Going Our Way (26 page)

Read The World Was Going Our Way Online

Authors: Christopher Andrew

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #True Accounts, #Espionage, #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #Military, #Intelligence & Espionage, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #Russia, #World

Though Soviet commentators continued to express ‘unswerving solidarity’ with the Nicaraguan people and ‘resolute condemnation’ of US aggression towards them, they failed to include Nicaragua on their list of Third World ‘socialist-oriented states’ - a label which would have implied greater confidence in, and commitment to, the survival of the Sandinista revolution than Moscow was willing to give. Both the Soviet Union and Cuba made clear to Sandinista leaders that they would not defend them against American attack. During Daniel Ortega’s visit to Moscow in March 1983, he was obliged - no doubt reluctantly - to assent to Andropov’s declaration as Soviet leader that ‘the revolutionary government of Nicaragua has all necessary resources to defend the motherland’. It did not, in other words, require further assistance from the Soviet Union to ‘uphold its freedom and independence’.

56

56

Ortega’s visit coincided with the beginning of the tensest period of Soviet-American relations since the Cuban missile crisis. Since May 1981 the KGB and GRU had been collaborating in operation RYAN, a global operation designed to collect intelligence on the presumed (though, in reality, non-existent) plans of the Reagan administration to launch a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union. For the next three years the Kremlin and the Centre were obsessed by what the Soviet ambassador in Washington, Anatoli Dobrynin, called a ‘paranoid interpretation’ of Reagan’s policy. Residencies in Western capitals, Tokyo and some Third World states were required to submit time-consuming fortnightly reports on signs of US and NATO preparations for nuclear attack. Many FCD officers stationed abroad were much less alarmist than the Centre and viewed operation RYAN with scome scepticism. None, however, was willing to put his career at risk by challenging the assumptions behind the operation. RYAN thus created a vicious circle of intelligence collection and assessment. Residencies were, in effect, required to report alarming information even if they were sceptical of it. The Centre was duly alarmed and demanded more. Reagan’s announcement of the SDI (‘Star Wars’) programme in March 1983, coupled with his almost simultaneous denunciation of the Soviet Union as an ‘evil empire’, raised Moscow’s fears to new heights. The American people, Andropov believed, were being psychologically prepared by the Reagan administration for nuclear war. On 28 September, already terminally ill, Andropov issued from his sickbed an apocalyptic denunciation of the ‘outrageous military psychosis’ which, he claimed, had taken hold of the United States: ‘The Reagan administration, in its imperial ambitions, goes so far that one begins to doubt whether Washington has any brakes at all preventing it from crossing the point at which any sober-minded person must stop.’

57

57

The overthrow of the Marxist regime in Grenada a few weeks later appeared to Moscow to provide further evidence of the United States’ ‘imperial ambitions’. In October 1983 a long-standing conflict between Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and his deputy, Bernard Coard, erupted in violence which culminated in the shooting of Bishop, his current lover and some of his leading supporters in front of a mural of Che Guevara. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher disagreed in their interpretation of the killings. The new regime, Mrs Thatcher believed, though it contained more obvious thugs, was not much different from its predecessor. Reagan, like Bill Casey, his DCI, regarded the coup as a serious escalation of the Communist threat to the Caribbean. Grenada, he believed, was ‘a Soviet-Cuban colony, being readied as a major military bastion to export terror and undermine democracy’. Reagan was also concerned at the threat to 800 American medical students in Grenada. On 25 October a US invasion overthrew the regime and rescued the students. The operation further fuelled Soviet paranoia. Vice-President Vasili Kuznetsov accused the Reagan administration of ‘making delirious plans for world domination’ which were ‘pushing mankind to the brink of disaster’. The Soviet press depicted Reagan himself as a ‘madman’. The Sandinistas feared that Nicaragua might be the next target for an American invasion. So did the KGB.

58

58

The impact of the Grenada invasion in Moscow was heightened by the fact that it immediately preceded the most fraught phase of operation RYAN. During the NATO command-post exercise, Able Archer 83, held from 2 to 11 November to practise nuclear release procedures, paranoia in the Centre reached dangerous levels. For a time the KGB leadership was haunted by the fear that the exercise might be intended as cover for a nuclear first strike. Some FCD officers stationed in the West were by now more concerned by the alarmism of the Centre than by the threat of Western surprise attack. Operation RYAN wound down (though it did not end) during 1984, helped by the death of its two main protagonists, Andropov and Defence Minister Ustinov, and by reassuring signals from London and Washington, both worried by intelligence reports on the rise in Soviet paranoia.

59

59

The period of acute US-Soviet tension which reached its peak late in 1983 left Moscow in no mood to raise the stakes in Central America. The Soviet-Nicaraguan arms treaty of 1981 had provided for the delivery of a squadron of MiG-21s in 1985. Moscow was well aware, however, that the supply of MiG-21s would be strongly opposed by the United States. Early in 1984 Castro began trying to persuade the Sandinista leadership that they should accept a squadron of helicopters instead. Humberto Ortega reacted angrily, telling a meeting of the Sandinista National Directorate: ‘It doesn’t seem at all unlikely to me that the Soviets, lining up their international interests, have asked Castro to persuade us to give up the MiG-21s. But we must never renounce them, nor must we allow Cuba to continue being an intermediary between ourselves and the Soviets.’ The MiG-21s, however, were never delivered.

60

In the mid-1980s Soviet bloc support for the Nicaraguan economy fluctuated between $150 and $400 million a year, all in bilateral trade credits rather than hard-currency loans - a significant drain on Soviet resources but a small fraction of the aid it gave to Cuba.

61

60

In the mid-1980s Soviet bloc support for the Nicaraguan economy fluctuated between $150 and $400 million a year, all in bilateral trade credits rather than hard-currency loans - a significant drain on Soviet resources but a small fraction of the aid it gave to Cuba.

61

For different reasons, Central America turned into a major policy failure for both the United States and the Soviet Union. The disorganized Contras (whose numbers, even on the most optimistic estimate, were never more than one-fifth those of the EPS) had no prospect of defeating the Sandinistas. Their inept guerrilla campaign served chiefly to discredit themselves and their American supporters. On 24 May 1984 the House voted another Boland Amendment, more drastic than the first. Signed into law by Reagan in October, Boland II (as it became known) prohibited military or paramilitary support for the Contras by the CIA, Defense ‘or any other agency or entity involved in intelligence activities’ for the next year. The Deputy Director for Intelligence (and future DCI), Robert Gates, wrote to the DCI, Bill Casey, on 14 December 1984:

The course we have been on (even before the funding cut-off) - as the last two years will testify - will result in further strengthening of the regime and a Communist Nicaragua which, allied with its Soviet and Cuban friends, will serve as the engine for the destabilization of Central America. Even a well-funded Contra movement cannot prevent this; indeed, relying on and supporting the Contras as our only action may actually hasten the ultimate unfortunate outcome.

The only way to bring down the Sandinistas, Gates argued, was overt military assistance to their opponents, coupled with ‘air strikes to destroy a considerable portion of Nicaragua’s military buildup’. Covert action could not do the job. Neither Casey nor Reagan was willing to face up to this uncomfortable truth.

62

62

The attempt to circumvent the congressional veto on aid to the Contras led the White House into the black comedy of ‘Iran-Contra’ - an illegal attempt to divert to the Contras the profits of secret arms sales to Iran, followed by an attempted cover-up. Though the word ‘impeachment’ was probably never uttered either by the President himself or by his advisers in their conversations with him during the Iran-Contra crisis, it was in all their minds after the affair became public knowledge at a press conference on 25 November 1986. White House reporters, Reagan’s chief-of-staff believed, were ‘thinking a single thought: another Presidency was about to destroy itself’. That evening Vice-President George Bush dictated for his diary a series of staccato phrases which summed up the despondency in the White House: ‘The administration is in disarray - foreign policy in disarray - cover-up - Who knew what when?’ US support for the Contras had proved hopelessly counterproductive, handing a propaganda victory to the Sandinistas and reducing the Reagan presidency to its lowest ebb.

63

63

Though the failures of US policy in Central America were eagerly exploited by Soviet active measures, however, Moscow was beginning to lose patience with the Sandinistas. In May 1986, despite the fact that Nicaragua already owed the Soviet Union $1.1 billion, the Politburo was still willing ‘to supply free of charge uniforms, food and medicine to seventy thousand servicemen of the Sandinista army’.

64

By 1987, with economic problems mounting at home, Gorbachev was increasingly reluctant to throw good money after bad in Central America. The Nicaraguan Minister of External Cooperation, Henry Ruiz, ruefully acknowledged that Soviet criticism of the Sandinistas’ chronic economic mismanagement was ‘legitimate’.

65

The economic pressure created by the decline of Soviet bloc support was heightened by a simultaneous US embargo. According to the secretary-general of the Sandinista Foreign Ministry, Alejandro Bendaña, Moscow told Managua bluntly that it was ‘time to achieve a regional settlement of security problems’. After three years of tortuous negotiations, continued conflict and missed deadlines, a peace plan chiefly devised by the Costa Rican President, Oscar Arias Sánchez, finally succeeded. According to Bendaña, ‘It wasn’t the intellectual brilliance of Oscar Arias that did it. It was us grabbing frantically onto any framework that was there, trying to cut our losses.’

66

As part of the peace plan, the Sandinistas agreed to internationally supervised elections in February 1990, and - much to their surprise - lost to a broad-based coalition of opposition parties.

64

By 1987, with economic problems mounting at home, Gorbachev was increasingly reluctant to throw good money after bad in Central America. The Nicaraguan Minister of External Cooperation, Henry Ruiz, ruefully acknowledged that Soviet criticism of the Sandinistas’ chronic economic mismanagement was ‘legitimate’.

65

The economic pressure created by the decline of Soviet bloc support was heightened by a simultaneous US embargo. According to the secretary-general of the Sandinista Foreign Ministry, Alejandro Bendaña, Moscow told Managua bluntly that it was ‘time to achieve a regional settlement of security problems’. After three years of tortuous negotiations, continued conflict and missed deadlines, a peace plan chiefly devised by the Costa Rican President, Oscar Arias Sánchez, finally succeeded. According to Bendaña, ‘It wasn’t the intellectual brilliance of Oscar Arias that did it. It was us grabbing frantically onto any framework that was there, trying to cut our losses.’

66

As part of the peace plan, the Sandinistas agreed to internationally supervised elections in February 1990, and - much to their surprise - lost to a broad-based coalition of opposition parties.

With the demise of the Sandinistas, Cuba was, once again, the only Marxist-Leninist state in Latin America. During the later 1980s, however, there was a curious inversion of the ideological positions of Cuba and the Soviet Union. Twenty years earlier, Castro had been suspected of heresy by Soviet leaders. In the Gorbachev era, by contrast, Castro increasingly saw himself as the defender of ideological orthodoxy against Soviet revisionism. By 1987 the KGB liaison mission in Havana was reporting to the Centre that the DGI was increasingly keeping it at arm’s length. The situation was judged so serious that the KGB Chairman, Viktor Chebrikov, flew to Cuba in an attempt to restore relations. He appears to have had little success.

67

Soon afterwards the Cuban resident in Prague, Florentino Aspillaga Lombard, defected to the United States and publicly revealed that the DGI had begun to target countries of the Soviet bloc. He also claimed, probably correctly, that Castro had a secret Swiss bank account ‘used to finance liberation movements, bribery of leaders and any personal whim of Castro’.

68

At the annual 26 July celebration in 1988 of the start of Castro’s rebellion thirty-five years earlier, the Soviet ambassador was conspicuous by his absence. In his speech Castro criticized Gorbachev publicly for the first time. Gorbachev’s emphasis on

glasnost

and

perestroika

was, he declared, a threat to fundamental socialist principles. Cuba must stand guard over the ideological purity of the revolution. Gorbachev’s visit to Cuba in April 1989 did little to mend fences.

67

Soon afterwards the Cuban resident in Prague, Florentino Aspillaga Lombard, defected to the United States and publicly revealed that the DGI had begun to target countries of the Soviet bloc. He also claimed, probably correctly, that Castro had a secret Swiss bank account ‘used to finance liberation movements, bribery of leaders and any personal whim of Castro’.

68

At the annual 26 July celebration in 1988 of the start of Castro’s rebellion thirty-five years earlier, the Soviet ambassador was conspicuous by his absence. In his speech Castro criticized Gorbachev publicly for the first time. Gorbachev’s emphasis on

glasnost

and

perestroika

was, he declared, a threat to fundamental socialist principles. Cuba must stand guard over the ideological purity of the revolution. Gorbachev’s visit to Cuba in April 1989 did little to mend fences.

The rapid disintegration of the Soviet bloc during the remainder of the year, so far from persuading Castro of the need for reform, merely reinforced his conviction that liberalization would threaten the survival of his regime. Gorbachev, he declared in May 1991, was responsible for ‘destroying the authority of the [Communist] Party’. News of the hard-line August coup was greeted with euphoria by the Cuban leadership. One Western diplomat reported that he had never seen Castro’s aides so happy. The euphoria, however, quickly gave way to deep dismay as the coup collapsed. The governments of the Russian Federation and the other states which emerged on the former territory of the Soviet Union quickly dismantled their links with Cuba. The rapid decline of Soviet bloc aid and trade had devastating consequences for the Cuban economy. Castro declared in 1992 that the disintegration of the Soviet Union was ‘worse for us than the October [Missile] Crisis’.

69

Never, even in his worst nightmares, had he dreamt that Cuba would be the only Marxist-Leninist one-party state outside Asia to survive into the twenty-first century.

69

Never, even in his worst nightmares, had he dreamt that Cuba would be the only Marxist-Leninist one-party state outside Asia to survive into the twenty-first century.

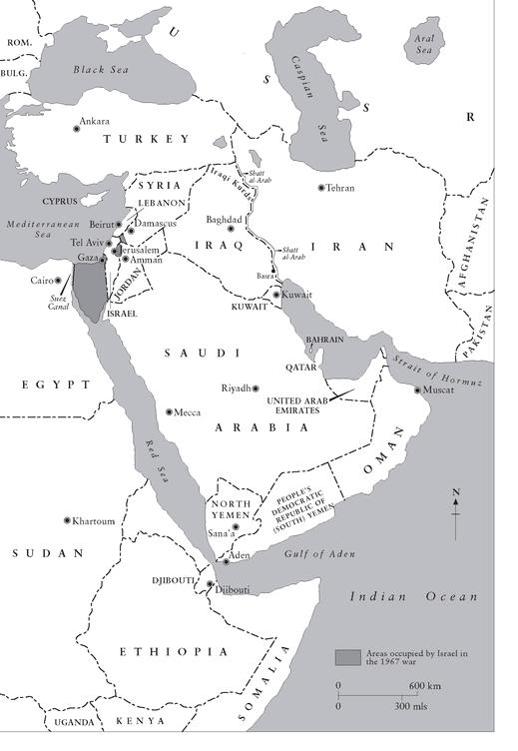

The Middle East

The Middle East in the Later Cold War

Other books

Blackfin Sky by Kat Ellis

The Innocent by Ann H. Gabhart

Uneasy alliances - Thieves World 11 by Robert Asprin, Lynn Abbey

Life After: Episode 4 (A Serial Novel) by Holden, JJ

Company by Max Barry

The Slightly Bruised Glory of Cedar B. Hartley by Martine Murray

Pursuit of a Parcel by Patricia Wentworth

Blood Junction by Caroline Carver

Unbroken by Emma Fawkes

Black Wings: New Tales of Lovecraftian Horror by S.T. Joshi