Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back (33 page)

Read Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back Online

Authors: Liz Owen

Inhaling, lift your trunk slightly and look forward. Exhaling, move more deeply into a forward bend as your hamstrings, hips, and spinal muscles release. As you gaze toward your legs, don't let your head or neck be “pushy”; by that I mean don't let them try to push your trunk into the pose. Repeat this process of mindfully moving for a few breaths, each breath offering an opportunity for your physical body to release into the pose and for your mind and emotions to come into a place of quiet and repose.

Stay in the pose for fifteen to twenty seconds, or longer if you are comfortable. When you are ready to come out, look forward and lift your spine halfway up, then reach your trunk and arms upward into a seated Upward Hand Pose before you release them to the floor.

Before you rest in a well-earned Child's Pose, check in with your lower back. If it feels tired from forward bending, lie down on your back and come into a very gentle

Bridge Pose

for ten seconds or so to return your lower back to its natural alignment, then hug your knees into your chest.

FIG. 4.27

Child's Pose and Deep Relaxation

Rest | Balasana and Shavasana Variation 3

Child's Pose is a great “go-to” pose at the end of any practice, especially when you've worked hard to strengthen, lengthen, and tone your back. And you've done just that! Rest now in

Child's Pose

for a few moments to completely relax your lower back. Visualize your lumbar spine once again as a luminous pearl necklace, now in a gentle upward curve supported by the flow of breath into your abdomen and lower back. Visualize each end of your lumbar spine gently floating down into a subtle upside-down U, one end meeting your sacral spine and the other meeting your thoracic spine. With each inhalation, visualize your breath as the necklace's threads, gently elongating and spreading the pearls apart from each other, and enjoy a

feeling of spaciousness in your lower back. With each exhalation, let the threads of the necklace soften and relax, releasing the pearls down so you can rest in the support of toned muscles and the flow of vital prana.

You may wish to continue to rest in the Shavasana we practiced

earlier

.

5

H

OW OFTEN DO YOU

think about your midsection? Your tummy? Your gut? Your “six-pack”? Your “twelve-pack”? I'm going to guess you spend a few hours each day focused on it without even realizing it.

If you are conscious of your body image, you probably think about your belly first thing in the morning and last thing at nightâlooking at it, judging it, letting it set your mood, and choosing your clothes for the day based on how flat, round, small, or big you think it is. Like with your lower back, you may also have invested in products marketed as quick fixes for your abs.

Your stomach is a highly communicative place in your body, in addition to being the source of body-image insecurity or pride. It prompts you to sit down to eat when you are hungry. It makes itself heard after you eat as well, either with pleasure when it feels full or with regret when you've eaten too much. If you are stressed out or tend toward anxiety, you may be hearing your stomach's call moreâor lessâoften than usual, or you may find yourself addressing stomach acid issues an hour after every meal.

Let's face itâwe are a stomach-obsessed culture, judging ourselves and others based on whether we can pinch more than an inch or have six-pack abs. Regardless of where on that spectrum you fall, it's likely you have a complicated relationship with your midsection.

The ancient yogis and other ancient cultures, though, understood the tremendous power that resides in the abdomen. They celebrated it as a source of creation, sensuality, and self-sustaining heat and energy from which we power ourselves throughout our lives.

You'll be happy to know that especially when seen through the yogic lens, you don't need six-pack abs to have excellent abdominal tone that supports and empowers the rest of your body. (Incidentally, on the topic of six-pack absâthough popular, the practice of “ab crunches” is not a favorite with me because crunches can irritate a sensitive lower back and overtighten psoas muscles. So there's no need to worryâwe won't be doing any crunches in this book.)

The title of this chapter is “Your Abdominal Core,” and I want you to take a moment to contemplate the notion of “core” before we dive in. Everything in your body, remember, is connected. Our work so far has painted a picture of the layers of wellness we're pursuing with our yoga practice: whole health starts with back health; back health starts with sacral health; sacral health requires hip and lumbar health. Now we come to the “core” from which all those other areas draw their strengthâor recruit their weakness.

The core of an apple or pear contains its seeds, its hope for a healthy, “fruitful” future. So too is your abdominal core your innermost wellspring of strength, support, and wellness. Let's explore it together.

T

HROUGH

W

ESTERN

E

YES: THE

P

HYSICAL

V

IEW

Your abdominal cavity is the largest cavity in your body. It includes the entire area from your pelvic floor muscles up to your diaphragm, encompassing the front, sides, and back of your middle body. It contains most of your internal organs, including the liver, spleen, pancreas, gall bladder, stomach, and intestines. Your abdomen isn't a mover or a shaker (well, sometimes it

does

shake . . . ) the way your arms, legs, and spine are, but it affects and is affected by how you engage the rest of your body with movements and posture alike. A toned and engaged abdominal core has plenty of room to hold your internal organs without compressing or stressing them. Very importantly for our purposes, a healthy abdominal core will also contribute to the stability and fluidity of your lower back.

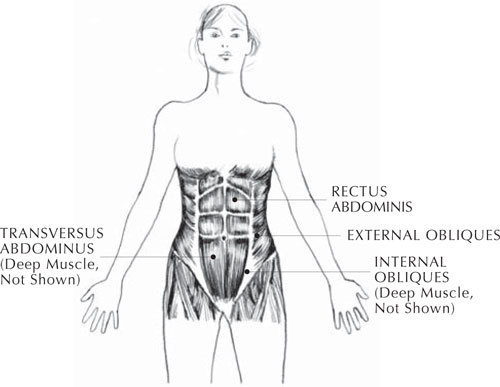

Your abdominal wall consists of four layers of muscles: the rectus abdominis, or the large muscles that run up the front of the abdomen; and the three layers of flat muscles that wrap around the abdomen. These “wrapping” muscles are the external obliques, internal obliques, and transversus abdominis muscles. More on each of those in a moment.

Together, the abdominal muscles act like flexible, woven layers of mesh that support your abdominal organs and lower back. They rotate your torso, help you bend forward and to the sides, and then they help you come back to an upright position. Toned abdominal muscles help protect your lumbar disks by supporting and stabilizing the movements of your spine. They also help you breathe, if you imagine a healthy breath as a three-dimensional action in which the rib cage expands forward, backward, and to the sides while the diaphragm rises and lowers into the abdominal cavity.

1

The term

abdominal core

is now commonplace in the yoga world, not to mention in the fitness and athletic industries. Each discipline has its own interpretation of what makes up your “core.” Sometimes just the innermost layers of abdominal and back muscles are included. Other definitions include the deep hip muscles, and other definitions go further to include the shoulders, hips, and legs. Since our main intention is to create a healthy lower back, we will focus on toning and balancing the musculature that directly affects the sacral and lumbar spines. So when I talk about the “abdominal core,” I'm including your abdominals as described above, plus your psoas muscles, which you explored in chapters 2 and 3, and the muscles of the lower back, which you explored in chapter 4. These three areas are intricately connectedâif the abdominals are weak and the psoas muscles are short, tight, or stronger than the abdominals, your lumbar spine will be pulled forward, straining the lower back and creating a lordosis (excess inward curvature of the lumbar spine). The lordosis in turn will tip your back hip bones forward, causing your lumbar muscles to shorten and tighten up, limiting your lower back's range of motion.

To avoid this dysfunction, this chapter focuses on toning and balancing your abdominal muscles so your abdominals, psoas, and lower back muscles work together with tone and balance. Then your abdominal core can support you and provide you with the mobility and flexibility you need to move through every day with ease and comfort.

Anatomy Lesson: Your Abdominal Muscles

As you continue on your journey toward a healthy lower back, it's worth taking the time to understand the basics of your abdominal muscles and how they help you in your daily life (

illustration 16

).

Let's start with the rectus abdominis, the outermost layer and the most prominent abdominal muscles. These muscles originate at the pubic bone and run along both sides of the linea alba, the flat band of connective tissue that runs along the center of your abdomen from your pubic bone to your breastbone. These are the muscles that are commonly called the “six-pack” because they are segmented into sections that become visible when the muscles are highly developed. The rectus abdominis help the spine and torso bend forward, and they stabilize your hips when you walk. Along with your psoas, they also control the tilt of your pelvic girdle, which is one reason these muscles are so important for your healthy lower back.

Illustration 16. The Muscles of the Abdominal Core

Next let's talk about the obliques. You have two sets of these important muscles. The external obliques are the large, broad muscles that run diagonally down and in from between your upper and middle ribs to the rim of your hip bones and the bottom of your linea alba. The internal obliques lie underneath the external obliques. They begin in the myofascia of the lower back and run up toward the midline of your body, to the upper ribs and the top of your linea alba. The obliques' primary function is in the rotation and side bending of your trunk. Toned internal and external oblique muscles support the lumbar spine during a twist, especially in that important spot between L5 and S1 where the disk is thicker and carries the weight and energy of a lot of movement. As I've said before, strong, healthy obliques maintain healthy pressure on the curve of the lower back, which helps to counteract any tendency of the lumbar spine to go into lordosis.

The deepest layer of muscles is the transversus abdominis. This set of muscles wraps horizontally all the way around your abdomen, starting at the lumbar and thoracic myofascia, passing over the lower ribs and iliac crest, and attaching to the linea alba and pubic bone in front. The transversus abdominis are often overlooked in conversations about your abdominal core because they aren't involved in the movement of your torso. But they are crucially important to your journey into wellness, as they act like a belt that supports the contents of your abdominal cavity.

The Brain-Gut Connection: The Vagus Nerve

Let's step back from muscles for a moment and discuss how your nervous system works in your abdominal core. One might call this the “brain-gut connection.” The most important channel of communication between your brain and the internal organs, including those in your abdominal core, is the vagus nerve. Not to be indelicate, but if you have ever gotten a stomach bug and felt your heart pounding, sweat pouring, and mind racingâeven to the point of passing outâyou are intimately familiar with how powerful the vagus nerve is when it's “upset.” At its best, though, the vagus nerve is an important pathway of relaxation and calm in your body. Yoga practice has a direct effect on the vagus nerve, so understanding it is valuable as we begin to work on your core.

The vagus nerve begins at the base of your brain and runs through your thoracic and abdominal cavities. It connects to and exerts control over most of your internal organs. In addition to conveying electrical impulses to your internal organs, it communicates information about the condition of your organs to your central nervous system. You may remember when I talked about the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) back in

chapter 1

. As part of its role as a liaison between your brain and organs, the vagus nerve controls parasympathetic stimulation of your heart, which can lead to a reduction in heart rate and blood pressure and creates a relaxation response throughout your body.

2