Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (135 page)

Still without a cadence, still in restless rhythms, the development settles down for a sustained stretch in D minor. From there without warning the recapitulation seems to erupt out of nowhere, assaulting the music with extraordinary effect: a

fortissimo

D-major chord with an F-sharp rather than a D in the bass. Beyond a harmony with an unstable note at its foundation, the D-major chord itself seems vertiginous and disorienting. In D major now, the falling-arpeggio theme breaks out. Here are a major chord and key violent in effect. The moment negates everything a recapitulation and a major chord are supposed to beâa release of tension, a homecoming. Here perhaps for the first time the movement clearly reveals its roots in violence and despair. It is one of the most original, unexpected, hair-raising moments Beethoven had created since the searing development climax and wrong-chord recapitulation in the

Eroica

. There the hero was triumphant. Here he is sowing ruin.

If the effect of the movement so far has been developmental and through-composed, the recapitulation is largely literal, settling down the explosion of the recapitulation. Then begins one of Beethoven's long codas, in length a quarter of the movement. It is a resumption of the development with some of its themes, but now as in the Fifth Symphony first movement, in the coda everything is made more intense, more forward-driving than the development proper.

At the end comes Beethoven's last shock in the movement. In the basses

pianissimo

begins an eerie chromatic moan. Above it the winds enact a striding theme that is unmistakably a funeral marchâin fact, it is derived from the Handel “Dead March” that Beethoven jotted down as he worked on the Ninth. Like the opening of the symphony, the chromatic moan rises, fills up the space until it has virtually taken over the orchestra around the deathly stride of the march, with its relentless dotted rhythms, louder and louder. Abruptly, with a return to the D-minor down-striding theme that has become nothing but death, the movement is over.

Even here, in this web of puzzles and images, Beethoven thought of the technical and emotional and symbolic at the same time. Over the years as he redistributed the weights and balances of the musical forms he inherited, more and more he was interested in end-weighted pieces, especially in the symphonies. As said before, this is a particularly difficult thing to do, to write a weighty and compelling first movement and then top it in the finale. The

Eroica

was surely intended as a step in that direction, but in musical terms as distinct from symbolic, there the finale arguably does not pay off the weight and the implications of the first movement. The Fifth may have been intended to be end-directed as well, and the triumphant finale is splendid, but the first movement still claims most of the attention.

In the Ninth he wanted the choral finale to be the goal and glory of the symphony. To that end, then, he radically destabilized the first movement, kept it unresolved, searching and not finding all the way to its end. By the end of the movement, everything is in flux, unsettled, so a climactic finale becomes indispensable. Here Beethoven definitively solved the problem he had grappled with for decades, making the finale the principal movement.

Like all the late music, the Ninth was not a new direction for Beethoven as much as a continued deepening and expansion of trends that had been in his music all along: bigger pieces, more intense contrasts, more complexity and more simplicity. The instrumentation follows suit. The Ninth and the

Missa solemnis

have the most colorful, variegated, innovative orchestration of his life. The Ninth's massive sound reaches far beyond the modest colors and textures of the eighteenth-century orchestra that Beethoven wielded in the First Symphony. Symphonies of that earlier time were written mainly for private orchestras that might have five or six violins, two or three violas and cellos, one bass. In the Ninth, string lines are often doubled in octaves; there are four horns and, in the second and last movements, trombones. The premiere involved a string section two to four times bigger than that of the usual palace or theater orchestra; the music is geared for that size string section, plus doubled winds. Given Beethoven's evolution of orchestral technique and color since the middle symphonies, it is astounding how innovative and fresh are the orchestral styles of the mass and the Ninth, shaped when their composer was close to stone deaf. That orchestral sound was to be a prime model for the coming Romantic generations of composers. Inevitably, in the symphony there are mistakes and miscalculations that Beethoven was not able to hear and fix in rehearsals. At times, the winds sound thin and unbalanced amid the massive string and brass sonorities. But mostly the sound is powerful and brilliantly variegated.

Can we glimpse what sort of meanings are adumbrated here? The end of the first movement leaves everything unresolved, unsettled, and unsettling. But the unfolding of Beethoven's music over the decades suggests a trajectory of symbol and implication.

The end of the first movement is Beethoven's third and last funeral march. The first two, the op. 26 Piano Sonata's “Funeral March on the Death of a Hero” and the same on a grander scale in the

Eroica

, were high-humanistic, echt-revolutionary evocations written in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, honoring a military hero as the highest exemplar of human achievement. In the Ninth, with his last funeral march, Beethoven buries another hero but in a far different, far more bitter and disillusioned context.

17

Written in the height of the idealism over Napoleon, the

Eroica

first movement depicted the creation of a hero, the other movements the aftermath of his triumph. In the wake of the fall of Napoleon, the destruction of what he once appeared to stand for, came the police states that followed the Congress of Vienna. Across Europe, the age of heroes and benevolent despots was finished. So among its implications, the first movement of the Ninth Symphony depicts that bitter endâthe deconstruction and burial of the heroic ideal, once and for all. That is the “despair” Beethoven wrote of. In the

Eroica

the conquering hero brought peace and happiness. In the Ninth the hero brings despair and death.

18

But within that despair are moments of hope, and it is those moments that prefigure the

Freude

theme.

19

Â

Each movement of the Ninth begins with not exactly an introduction but rather a kind of curtain-raiser. In the first movement it is the whispering emergence from the void. In the second movement it is bold, dancing, down-leaping octaves in strings and winds and, as an impudent interruption, crashing F-to-F octaves in timpani. Beethoven places the scherzo as the second movement instead of the usual third, something not unprecedented but new to his symphonies. Beethoven had stopped calling these movements “scherzo” after the Fourth Symphony, perhaps because he did not like the joking implication of the word, which is irrelevant to the tone of the Fifth Symphony scherzo.

20

All the movements of the Ninth are grounded on D and the scherzo is in D minor, but not a tragic D minor. It is a vivacious, puckish, indefatigable

moto perpetuo

. Those qualities in a minor key give the scherzo a distinctive tone, a tinge of irony. At the same time there is a frenetic quality that recalls Beethoven's sketch years before, imagining “a celebration of Bacchus,” something on the order of a revel, a drunken frenzy in manic counterpoint.

The movement is another of his graftings of fugue and sonata, the scherzo section a fully-worked-out sonata form. At the same time it has the familiar scherzoâtrioâscherzo layout. The gist of the treatment is that the opening tune is both fugue subject and sonata-form first theme, introduced in a fugue and thereafter developed as a theme. This is Beethoven's most complexly contrapuntal scherzoâat the same time, with its kinetic and memorable subject, one of his most crowd-pleasing.

The harmony is far more stable than in the first movement, but from the beginning there is a wild card: the timpani, which is apt to barge in with its Fs in octaves rather than the time's almost unvarying DâA tuning of a movement in D.

21

Besides unsettling the D minor of the theme, in the development the timpani's Fs take the music into F and E-flat major, and they usher in the recapitulation.

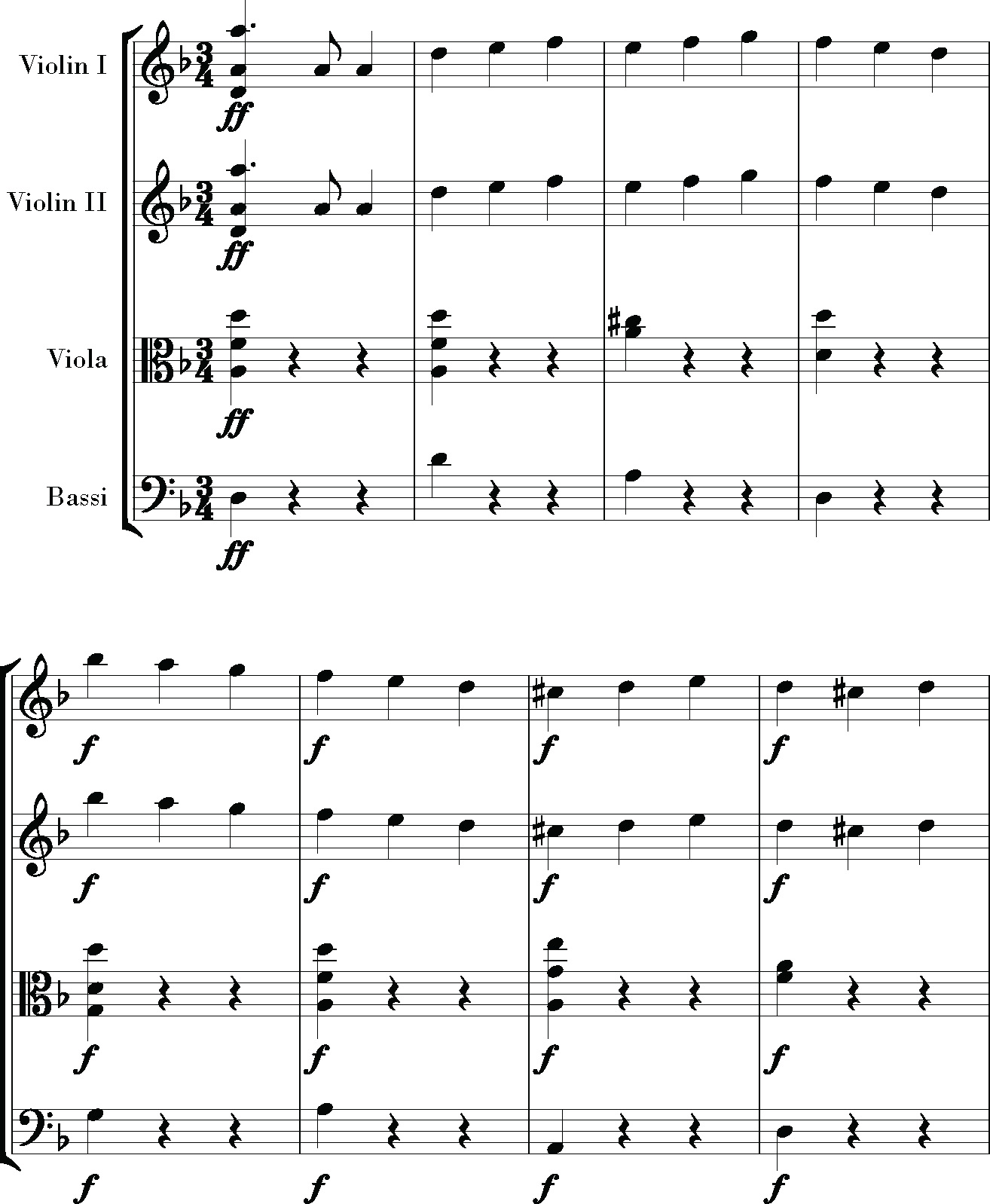

After its short and explosive curtain-raiser, the fugue takes off as if it were already in stretto, the entrances of the subject coming in every four beats. The first-theme section ends with the theme in glory, the fugal treatment left behind in the mad rush:

Â

Â

The second theme arrives as a more lyrical interlude, its lines hinting at the

Freude

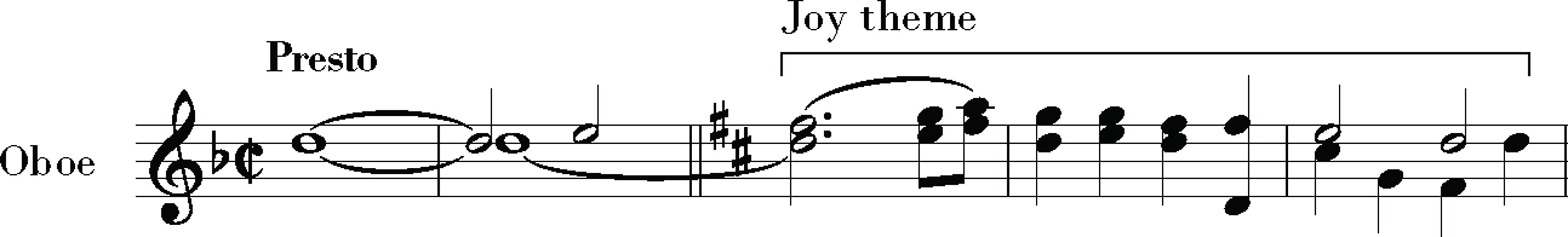

theme. The development begins with a droll harmonic sequence in falling thirds that starts on E-flat and ends when it reaches B major, the twelfth chromatic note in the bass. There follows a protean and indefatigable development section entirely given to the main theme, one part of the treatment being a switch between four-bar and three-bar phrasing of the one-beat meterâa novel effect in those days.

At the trio the D minor shifts to major, triple shifts to duple, complexity gives way to simplicity, and Beethoven commences one of his most delightful and surprising episodes: over a drone, a little wisp of folk song like you'd whistle on a sunny afternoon, growing through swelling repetitions into something hypnotic and monumental. It is recognizable as a musette, named for a droning folk bagpipe, a musical topic going back more than a century and always associated with an ingenuous and pastoral atmosphere. The theme enfolds the opening notes of the

Freude

theme in a different rhythm:

Â

Â

After the return of the scherzo, a largely literal recapitulation, Beethoven makes a feint at repeating the trio and then jokingly jumps into a mocking two-beat for a precipitous end.

So the second movement is made of complexity counterpoised by almost childlike simplicity. It is a striking choice to follow the deathly conclusion of the first movement. To say again, Beethoven has largely left behind the transparent dramatic arcs of his middle years, like the tragic one of the

Appassionata

and the triumphant one of the Fifth Symphony. Certainly the effect of the Ninth's second movement is different from Beethoven's other minor-key scherzo in the symphonies, the one in the Fifth with its touch of his C-minor demonic mood. Call the frenzied quality and the minor key of the Ninth's scherzo a fiercely seized Bacchic gaiety, a desperate forgetting, a mocking riposte to the dark D minor of the first movement. Or call it an echo of the tarantella, in which you dance madly to survive the poison of the tarantula.

Â

Every movement of the

Eroica

lies somewhere between ad hoc in form and a variant of a familiar form. Likewise in the Ninth. A stretch of sublime peace and reverie after the frenzied scherzo, the slow movement in B-flatâthe other harmonic pole of the symphonyâis founded on the idea of double variations, a genre shaped mainly by Haydn. The two themes, call them A and B, alternate and vary as they return. There ends the Haydnesque aspect of these double variations. For one thing, the themes in double variations are usually contrasting, often one in major and the other in minor. Here both themes are in major, the keys change, and the two themes contrast minimally: both have a long-breathed, lyrical beauty, the second more flowing and lilting.

Marked Adagio molto e cantabile, very slow and singing, the movement begins with a sighing curtain-raiser of two bars. The opening A theme in B-flat major is one of Beethoven's broad, ineffably noble melodies whose ancestors include the slow movement of the

Pathétique

. Its texture is intimate like that of a string quartet, the cellos alone on the bass line. In a long-unfolding melody of varying phrasing, without hurry it drifts down from B-flat to D below the staff, then over the next twelve bars slowly wends its way up to B-flat above the staff, then sinks down an octave. It is the kind of theme that in the next generation Wagner would name

unendliche Melodie

, floating free of the regular phrasing of Classical themes. Prophecies of the

Freude

theme are hinted in its three-note rising and falling figures. Also like the

Freude

theme, this one involves internal repeats of phrases, here in call-and-response between strings and winds.