Brain Trust (21 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

On the personal side, Knutson knows how to change these activation patterns. For example, beware the lure of bargains, which light your brain’s reward pathways irrespective of whether the bargain price is actually low, allowing the reward area of your brain an extra bargaining chip to use against your stodgy prefrontal. But most important, Knutson found that paying with credit lit the nay-saying prefrontal less than paying the same amount with cash—“anesthetizing the money loss,” he says.

If you want to dampen your shopping impulse, pay cash, not credit. And when you hit a bargain, allow your brain that extra second (or day) to think twice—reason overruling impulse—do you really need that battery-operated tie rack, even if it is 50 percent off?

Steve Schlozman, codirector of the Harvard

Medical School psychiatry program says, “The balance between the frontal lobe’s executive function and the amygdala’s base instincts is what makes us human.” And he offers imbalance as the cause of zombiism. In his decidedly tongue-in-cheek scenario, a decayed frontal lobe would leave no check for the anger and lust of the zombie amygdala. Schlozman also points out that the National Institutes of Health’s definition of cerebellar degeneration describes a “wide-base, unsteady, lurching walk, often accompanied by a back and forth tremor in the trunk of the body.” And degeneration of the hypothalamus can result in an insatiable hunger. In Schlozman’s opinion, exactly this damage could be caused by a mutated influenza, which would be especially transmittable, say, by bite. The zombie tide is real, baby. And it’s coming to get you. (For more science-of-the-undead fun, Google “Schlozman zombie podcast.”)

Puzzle #9:

Boomerang v. Zombie

Our hero throws a boomerang in the attempt to decapitate a zombie standing 30 yards away. But two seconds after he releases the ’rang, the zombie charges. The boomerang tracks a perfect circle at 30 mph, and the zombie instantly lurches to a surprisingly speedy 15 mph (no “Romero” zombie is this, apparently). Here’s the question: Should our hero stand his ground and await the return of his weapon, or one second after the zombie charges, should he run at 10 mph toward a tree 8 yards directly behind him that would take him 2 seconds to climb to the height of safety?

Gossip’s bad, right? According to Tim Hallett, social psychologist at Indiana University, it depends on your point of view. “Gossip is a weapon of the weak,” says Hallett. “Like the French Revolution, it’s a way the powerless band together to retake power from authority.”

In his study, the proletariat was composed of middle school teachers, and playing the part of a soon-to-be-noggin-challenged French noble was a new principal with an authoritarian administrative style and awkward social skills. Hallett videotaped these teachers as they went about their business—in conversations, in the teachers’ lounge, and especially in teacher-led formal meetings—generating more than four hundred pages of single-spaced transcripts.

He coded the language of these transcripts and explored the data for insights into the inner workings of gossip.

One thing Hallett found is that “Gossip is a ubiquitous part of everyday life—it’s unrealistic to ban it formally.” If you’re on the monarchy side of the revolution and thus have the goal of squishing gossip, banning it simply makes it more covert and potentially more insidious. Instead, providing a clear channel to voice discontent and clear mechanisms for getting things done in general removes the need for gossip to fill these roles. (Interestingly, elsewhere in this book economist Eli Berman recommends squishing terrorist organizations by increasing government social services, thus removing the population’s need to turn to splinter groups for this help.)

Unfortunately, in the school Hallett studied, neither of these conditions was met and so gossip ran rampant. The task went

from reducing its occurrence to “managing it informally by understanding how it works,” says Hallett.

“First, the best thing to do is have lots of friends,” he says. This seems obvious—if you’re liked and respected, people are less likely to say bad things about you—but it also means that if gossip happens to turn against you, you’re likely to have allies within earshot willing to deflect the damage. Assuming you or a friend is present, here’s how to deflect the course of gossip.

In the early stages, Hallett found that gossipers were tentative, exploring the loyalties of the group in a way that allowed plausible deniability should a group member prove loyal to the monarchy. One way to do this is through sarcasm. “If the gossip gets back to the position of authority, sarcasm allows the gossiper to insist she was being literal, like ‘I

said

you did a really good job!’ ”

Another obfuscation Hallett saw that attempted to infer bad things without saying them outright was something he called “praising the predecessor,” as in a teacher describing conditions under the past administration as “so calm, and you could teach. There was no one constantly looking over your shoulder.” What does this imply about the current administrator? This technique of praise as detraction works in any case of glaringly obvious comparison, as in a wife pointing out to her husband that her ex-boyfriend was such a good cook!

It’s in this early evaluative stage that gossip can most easily be steered or diffused. To combat sarcasm or comparative praise, ask for clarification—force the gossiper to speak literally and thus take responsibility for the true meaning of the comments. Or try a preemptive positive evaluation—follow a loaded opening question (Did you see the boss’s new shoes?) with abject praise (Yeah—Velcro’s back, baby!). If all else fails, switch the gossip to an innocuous target (Dude, that was nothing—did you see the shoes on Steve from accounting?).

Nipping detrimental gossip adroitly in its early stages—before gossipers discover everyone’s loyalties—can allow you to save the target of gossip without putting your head alongside his or hers on the chopping block of the resistance.

In another study, Hallett found a positive

feedback loop for the spread of emotion through a workplace—if a person naturally or intentionally starts broadcasting an emotion, it not only spreads by interaction, but as it spreads the original emotion also amplifies. This, of course, causes more spreading and more amplification until the emotion, in Hallett’s words, “blows up.”

Puzzle #10:

The Gossip Web

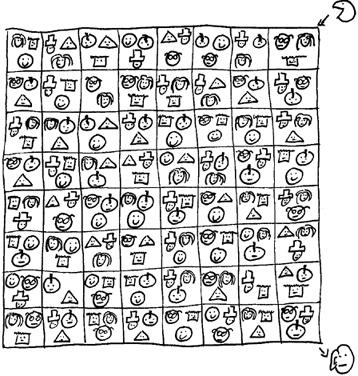

Did you hear that Annabel and Mark told everybody they’d baked the cupcakes for the party, but actually bought them at the bakery in the next town over? Can you guide the important message through the social network on

this page

? The message can only travel between touching boxes (no diagonals), and must be brought into any next box by someone in the first. For example, to get from the starting box to the one below it, you could go guy-with-glasses to guy-with-glasses. Then continuing down the column, you could go top-hat to top-hat.

“Parents want both kids to be happy with the piece of cake they get,” says Eric Maskin, economist at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. A parent can do his or her best to cut the cake evenly, but the problem is, “the kids themselves might not see this as an equal split,” he says. In addition to the perception of size inequality, maybe only one piece has a sugar Batman, or maybe one is slightly more endowed with frosting. These things may matter more than you could possibly imagine—they may have different “utilities” to different kids. So parents

of kids who have reached sharp-knife age use the time-honored trick of divide-and-choose, in which one kid cuts and the other kid picks. “The reason this works,” says Maskin, “is that the kid cutting the cake has an incentive to make the pieces equal.”

In the language of economists and game theorists this clean, simple, elegant cake-dividing procedure is a “mechanism.”

Eric Maskin designs similar mechanisms for things like carbon treaties—he won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for pioneering the field—only in the case of carbon cuts, no country in the world wants to get stuck with the bigger piece of cake. “The goal of mechanism design theory is to come up with the combination of concessions that gives everyone a positive payout,” says Maskin. And just like the cake, this is possible because what’s cheap to you might be dear to me—things like technological assistance, development aid, preferential trade agreements, international or domestic political capital, military assistance, a cleaner environment, etc., can have different utilities for different countries. Maybe giving some amount of technological assistance costs the United States 4 “chits,” but the same assistance is worth 8 chits to Brazil. An efficient treaty would ask Brazil to pay for this assistance with 7.99 chits of carbon reductions, which might be worth more to the United States in political capital than the 4 chits of tech assistance it paid. Because both countries come out ahead, both would sign the treaty. And then we would all stand arm in arm atop a hill drinking Coca-Cola and singing.

This idea of personal, differing utility allows you to amiably divide many things. Think about splitting up household chores—maybe you’d do the dishes and the laundry if your spouse will set a mousetrap in the garage. Or imagine dividing a Sunday’s worth of free time—is it worth six hours of strolling hand in hand on the beach for two hours of uninterrupted viewing of the Chelsea v. Manchester United game?

The variable utility of cutting cake and carbon also allows you

to split the restaurant bill with a group of friends. It’s not fair to split the bill evenly—you’re not going to freeload lobster when all I got was a grilled cheese sandwich! (This is the venerable problem called “the diner’s dilemma,” but that’s another long story.)

So imagine you’re not splitting the bill evenly. Who should pay a bit more and who should be silently allowed to pay a bit less? Well, what’s an extra $10.00 actually worth to you in terms of utility? Like cutting carbon, what somewhat intangible concessions might you get for paying extra? Might you gain the equivalent of $10.01 in goodwill? (The same amount of goodwill might only have $1.50 in utility to your cash-strapped high school buddy who still lives at home.) Does withholding $10.00 from the pot actually cost you $10.01 in the utility of reduced sex appeal due to looking like a cheapskate?

A good mechanism is efficient—everyone maximizes his or her personal utility by giving up what’s cheap to gain what’s dear, thus coming out ahead on aggregate. It might only take a little tricky utility shuffling to make a good deal all around. And at the very least, next time you get stuck paying the extra ten bucks on the tab, you’ll be aware that you got something for it.

Puzzle #11:

Cake Cutting

For whatever reason, you’ve chosen DIY cake cutting over allowing your two kids to divide-and-choose. Now the problem is how to divide the cake evenly. Imagine the small pan is a perfect 10 × 8-inch rectangle, 2 inches deep. On one side sits an undividable sugar Batman, worth exactly 27 in

3

of cake to kid A and 8 in

3

to kid B. But it’s kid B’s birthday and so both see it as fair if kid B’s piece is 1.5 times as big as kid A’s. (What? Isn’t this how it works in your family?) Who should get the sugar Batman, and how much cake should each kid get?