Brain Trust (23 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

Admit it: You’d love to—just once!—do a karaoke version of “Pinball Wizard” while standing on a bar in a sequined cape, codpiece, and oversized sunglasses.

Or is that just me? Anyway.… you can’t. That’s because

it’s no fun to party alone, and the 150 people you know would excommunicate you for the “Pinball” incident. In fact, Robin Dunbar, director of the Institute for Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology at Oxford University, has shown that people in societies around the world tend toward this magic number of 150 as what he calls “the cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom any single person can maintain stable relationships.” It’s true in Tennessee, it’s true in South Africa, and it’s also true on Facebook. “Actually the average number of Facebook friends is between 120 and 130,” says Dunbar, “perhaps because the other 20 or so people include Granny and the like, who aren’t online.”

So your goal is this: to act depraved while minimizing the damage to your 150-person network. The key is to pick just the right friends to party with. “In dense networks, people police the community,” says Dunbar. You see this in the Amish or Hutterites. “If you do something offensive, you offend everyone in your community and become a social outcast.” But Dunbar can show a developing trend toward more splintered networks. “Now, it may be that you’re born in San Francisco, go to school in New York, and get a job in Florida,” he says, meaning that your network is fragmented into perhaps five independent fingers of thirty people each. If you party with just the right, small splinter, the rest of your network need never know.

The trick is remaining hyperaware that whomever you party with will post pictures of you in a codpiece back to their own Facebook accounts, which will then be seen by all their friends. Are there people in your small, potential party splinter who are members of multiple lists? For example, is one of your college friends also on your list of current work buddies? If so, you may not be able to party with college friends for fear of your behavior leaking between groups and generally going viral through your 150-person network.

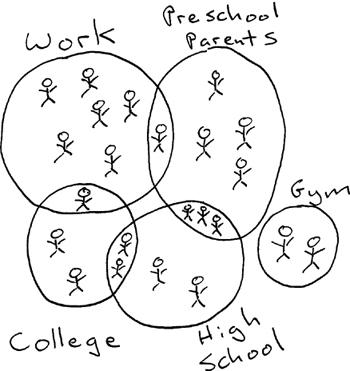

Rewrite your friends lists as a Venn diagram as shown below.

Now look for circles with the least (or no) overlap. If your friend circles are unusually dense, with unavoidable overlap—more Hutterite than modern American—look for the overlap with the shortest reach.

Now read this book’s entry about identity economics to discover how much your depraved behavior is likely to cost you in any given splinter (acting contrary to your expected identity carries a cost in “personal utility”—and you may have different identities in different splinter groups). Imagine the identity cost in any group multiplied by the number of people in the group. How much does your desired brand of depravity cost you?

The splinter with the least cost, gentle reader, is the group with which you should sing “Pinball Wizard.”

Dunbar’s recent work finds that people with

large social networks have distinctly looser emotional ties to most members. And so it’s as if, instead of being bound by the number 150, the size of a social network is bound by a finite amount of emotional energy, which a person can choose to distribute as they see fit.

Puzzle #12:

Friends Add Up

You have friends from grade school, high school, summer camp, college, your first job, grad school, your kids’ friends’ parents, an online fantasy football league, and your current job. If friend groups can only be composed of 13, 15, 17, or 32 individuals and each subsequent friend group (in listed order) has equal to or greater than the number of friends as the previous group, how many friends does each group have in order for your total number of friends to be exactly 150?

“There’s this old question in sociology asking

why your opinions and interests are similar to those of your friends,” says MacArthur genius and Cornell computer scientist John Kleinberg. “Do your friends influence you to become more like them, or do you seek out like-minded friends?” Kleinberg answered this question using Wikipedia, where you can quantifiably see that people who talk have similar editing behavior. Great, you’re like your friends. Only, by downloading the multiterabyte file that holds all of Wikipedia’s history, Kleinberg was able to ask if “similarity in editing behavior started before or after people started talking to each other.” What you see is this: “As people get closer to each other in the network, their editing behaviors become much more similar,” says Kleinberg, “but after they meet, their editing becomes only marginally more similar.” So the answer to sociology’s question is this: You seek out like-minded friends.

In a recent fit of optimism, I joined a gym. And the day I signed up, I noticed a police officer poking around the gym lobby. When I asked the membership agent about it, he told me that the day before, someone had stolen a spinning bike (like the life-sucking machine in

The Princess Bride

). It had been there at the 5:30 p.m. class, but was gone at the 7:00 p.m. class. There’s only one exit that doesn’t set off a fire alarm, and the exit leads through a crowded gym, down the stairs, and past the staffed front desk.

In other words, someone had walked out the door with a one-hundred-pound bike in plain view of at least ten and likely fifty

people. Maybe it was under a huge tarp or something, but still … don’t you think you would’ve noticed?

Maybe, maybe not. Check this out.

While both at Harvard, psychologists Dan Simons (now at the University of Illinois) and Christopher Chabris (Union College) filmed six people passing a basketball. Three wore white shirts and three wore black shirts. In the video they jump around while inexpertly bouncing and tossing the ball from one person to the next. Simons and Chabris showed subjects this film and asked them to count the number of passes by one or the other team. After the film they asked subjects if, just maybe, they noticed anything strange or unexpected during the film.

Half didn’t.

This, despite the fact that a woman in a gorilla suit walks obviously into the center of the group, stops to look at the camera, and thumps her chest before continuing off screen.

Again, people failed to notice a lady in a fricking gorilla suit. You can find the video online by searching for “invisible gorilla,” which is also the title of the duo’s very well written, thoroughly researched, and entertaining book.

First, this is potentially the coolest experimental design ever. Second, again—Dude, a gorilla suit! Come on!

But the experiment isn’t a one-hit wonder of coolness. Simons and another collaborator—Daniel Levin—ran a study that starts with a researcher stopping a stranger to ask directions. Great. Then two people carrying a large door walk through the middle of their conversation. And during the short time of obfuscation, the researcher grabs the door and one of the carriers takes his place. When the door passes, this new person picks up the conversation where it left off.

Imagine the mind trip: You’re talking to someone who magically and immediately morphs into an entirely new person. It’s enough to make you infarct something. That is, assuming you

notice at all. Again, as you can see with a quick online video search, half of us don’t.

Granted, these two studies are different—the first explores selective attention, and the second explores change blindness—but they both nicely demonstrate that people can be massively oblivious to even the patently obvious.

So it’s very possible to carry a spinning bike through a crowded gym without anyone’s noticing. Note this is very different from people’s noticing and not intervening—that jumps into the realm of bystander apathy, with the decision to help or not help a victim depending on behavioral economic payoffs like risk, reward, and relatedness (see this book’s entry on altruism). No, here we’re dealing with another thing entirely: The bystanders are completely unaware of the crime.

So … how might you take advantage of this phenomenon?

In a nice twist on the original gorilla experiment (for which the good doctors received an Ig Noble Prize), Simons and Chabris asked subjects not only to count the number of passes on one team or the other, but to keep track of the number that were bounce passes or chest passes. “With a higher cognitive load, people notice the gorilla even less,” says Chabris.

Simons explains, “We have a limited pool of attention. If you’re paying a lot of attention to something, you have less attention available to spend on noticing other things. This helps us focus on important things while filtering out distractions. One consequence of filtering out distractions, though, is that we sometimes filter out things that we might want to see.”

Like a lady in gorilla suit. Or the fact that your conversation partner has shape-shifted. Or someone lugging a spinning bike past the gym’s front desk.

So if you’re trying to do the lugging, do it among people whose brains are otherwise occupied. During the Final Jeopardy round

is ideal. If not, the age-old technique of an accomplice creating a distraction is a good one—and it doesn’t even need to pull attention away from your physical space as long as it takes up bystanders’ mental space. Perhaps your accomplice can aggressively shout brain teasers?

Also, “if a bank robber has a gun, bystanders are less likely to remember his face,” says Simons. Paying well-deserved attention to the gun detracts from the attention available for face recognition. This is similar to the theory of garish invisibility employed by Bill Murray in the underappreciated 1990 movie

Quick Change

, in which Murray flamboyantly navigates an airport in a clown suit while escaping after robbing a bank. While not exactly lab conditions, it’s as if people see the clown suit and not the wearer.

As for the exercise bike, I’m sorry to report the mystery was never solved.

Simons and Chabris also happen to be

freakishly good at chess. (Chabris has been a chess master since 1986, was editor of

Chess Horizons

, and founded the

American Chess Journal

.) Chess is a fertile ground for researchers because there are rankings—you know quantitatively how good people are. And Chabris and Simons used this data to find something cool: Players with lower rankings massively overestimated how good they were, while players with higher rankings were much closer in their estimations of their skill. (See this book’s entry with David Dunning.)

OK, here’s the situation: In the short time your kids are at preschool, you have to deposit a check, buy organic gummy vitamins with iron at the hippie grocery co-op, buy Drano at the nonhippie supermart (while avoiding eye contact with anyone you might’ve seen at the first), pick up dog food, drop off overdue books at the library, and get a bike tire repaired.

Six errands flung to the far corners of town, with a web of connecting roads and a ticking clock. Do you hear the

Mission Impossible

theme music? Go!