Enemy on the Euphrates (3 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

Senior political officer responsible for the Dulaym Division in occupied Iraq.

Second in command in Iraq at the time of the uprising. Commander of the Anglo-Indian troops in the key, mid-Euphrates region until his dismissal by Haldane in November 1920.

Self-made businessman with strong government contacts and ambitions to control shipping on the Tigris and Euphrates. One of the two government-appointed directors on the board of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

Catholic Tory landowner and amateur orientalist. Together with Hankey, a member of the De Bunsen Committee. In 1918, author of the Baghdad Declaration and the Anglo-French Declaration, both offering self-rule in Iraq.

Indian Army political officer and acting civil commissioner (head of the occupation administration) in Iraq until October 1920. Later, managing director of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

EMIR ‘ABDALLAH

Second son of Emir Husayn al-Hashimi, Sharif of Mecca. In early 1920 he was the favoured candidate of the nationalists to lead an independent Iraq.

Iraqi-born Ottoman army officer and member of the secret anti-Turkish organisation al-‘Ahd who deserted to the British during the war. Returned to Iraq towards the end of the 1920 revolution to become defence minister in a puppet government controlled by Britain. Brother-in-law of Nuri al-Sa’id.

Former Ottoman official and leading member of the nationalist Haras al-Istiqlal. One of the founders of the Ahliyya public school in Baghdad whose teachers and alumni agitated against the British occupation.

Junior officer from Mosul in the Ottoman army and member of al-‘Ahd, the secret society of (mainly Iraqi) Arab officers opposed to the Turkish dictatorship. Defected to the British during the war. Returned to Iraq towards the end of the 1920 uprising.

Third son of Husayn, Sharif of Mecca. Protégé of Lawrence during and after the Arab Revolt against the Turks. Emir of semi-independent Arab state of Syria (1918–20). In 1921, placed on the throne of Iraq in a move engineered by Churchill, Bell and Lawrence.

Sharif of Mecca and, later, King of the Hejaz. In late 1920 his short-lived kingdom provided sanctuary for some of the leaders of the Iraqi insurrection, including Ja‘far Abu al-Timman, Yusuf Suwaydi and Sayyid Muhsin Abu Tabikh, but avoided providing any material aid to the uprising for fear of losing British political support.

Senior mujtahid of Persian origin based at Najaf who took over leadership of the uprising after the death of Mirza Muhammad Taqi al-Shirazi.

Son of the Grand Mujtahid Mirza Muhammad Taqi al-Shirazi. President of al-Jam‘iyya al-‘Iraqiyya al-‘Arabiyya which stood for Iraqi collaboration with the Turkish nationalist leader Mustafa Kemal and the Bolsheviks. Exiled to Persia by the British in 1920 before the outbreak of the insurrection.

Iraqi-born junior Ottoman army officer and member of the secret anti-Turkish organisation al-‘Ahd who deserted to the British during the war. Returned to Iraq towards the end of the 1920 insurrection after offering his services to the British in crushing the uprising. Brother-in-law of Ja‘far al-‘Askari.

Son of the Kadhimayn mujtahid Sayyid Hasan al-Sadr. Along with ‘Ali al-Bazirgan, one of the founders of the Ahliyya public school in Baghdad, a hotbed of nationalist agitation. Leading member of the nationalist Haras al-Istiqlal and insurgent commander during the insurrection.

Shi‘i Grand Mujtahid of Persian origin and spiritual leader of the 1920 uprising. Died in August 1920 in Karbela’ at the height of the rebellion.

Elderly Baghdad Sunni notable and leading member of the nationalist Haras al-Istiqlal.

Wealthy landowning sayyid and veteran of the jihad against the British invasion in 1914–15. One of the principal leaders of the uprising in the mid-Euphrates region, he was appointed mutasarrif, to govern insurgent-controlled territory.

Baghdad Shi‘i merchant and one of the most important leaders of the nationalist organisation Haras al-Istiqlal. Campaigned for the Shi‘i and Sunni Muslims to unite against the British occupation.

PART ONE

Invasion, Jihad and Occupation

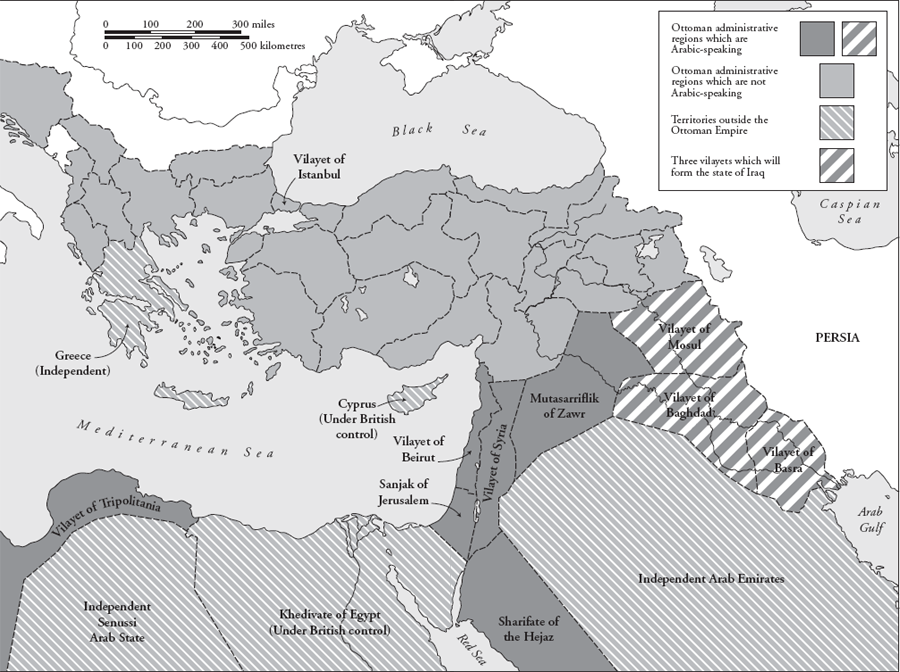

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE C.1900, SHOWING THE PREDOMINANTLY ARABIC-SPEAKING VILAYETS AND OTHER ADMINISTRATIVE REGIONS

Sir Mark Sykes, May 1913

Indications of Oil

One morning sometime in October 1905 – we don’t know precisely when or where – the twenty-six-year-old Sir Mark Sykes, ‘honorary attaché’ at the British embassy in Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Empire, made contact with an employee of a German engineering company surveying the territory of northern Iraq for the planned Berlin to Baghdad Railway. Perhaps they met in one of those ubiquitous Istanbul coffee houses, sipping that dark viscous liquid flavoured with cardamom, chatting and smoking just like any pair of European merchants doing a little business. We do know, however, that at some stage in the proceedings, the German gentleman passed a small package to Sykes which he quickly slipped inside his jacket pocket and in return – so we might reasonably surmise – an equally small package containing a sum of money was passed to the German engineer. Back at the embassy, Sir Mark unwrapped the package and checked the contents of the small notebook which it contained. Satisfied that the material he had been promised was actually there, he telephoned the British ambassador, Sir Nicholas R. O’Conor, to arrange an appointment with him at the ambassador’s earliest convenience.

Sir Mark Sykes was no ordinary junior embassy official. He was the only son of Sir Tatton Sykes, an extremely wealthy landowning grandee with estates in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Over the previous ten years he had travelled widely in the territories of the Ottoman Empire and had gained the reputation of being an expert on ‘the East’. Over the next ten years he would become, successively, the Conservative Member for the parliamentary constituency of Hull Central, the commander of the

Yorkshire Territorial Army Battalion and the personal representative of the war minister, Lord Herbert Horatio Kitchener of Khartoum, in all matters pertaining to British strategic and commercial interests in the Middle East. By 1916 he would be the government advisor whose opinions, ideals and prejudices were the most influential factor shaping the British Empire’s war aims in the struggle against the Ottoman Empire.

Sykes’s chief, O’Conor, a tall, languid Irish landowner and Britain’s ambassador in Istanbul (which the British persisted in calling Constantinople) since 1898, was rather fond of his earnest young attaché, a fellow Catholic, who seemed happy to relieve him of some of the more tedious diplomatic work. Moreover, in those years before the First World War, O’Conor and Sykes shared a certain affection for the old Ottoman Empire. This once-great multiethnic and multireligious super-state, with a population of 21 million (a third of whom were Arabs) distributed over thirty-three vilayets and stretching from the Balkans to the frontier with Persia, had long since become critically weakened by a combination of war, rebellion, debt and the economic penetration of European capitalism. It was debt in particular that was the Achilles heel of the Ottoman state. Failure to repay immense loans from European banks had resulted in the creation of a European-controlled Ottoman Public Debt Administration which syphoned off the empire’s taxes and customs duties. Britain was part of that organisation, but since the 1850s had also seen the Ottomans as a useful bulwark against tsarist Russia’s attempts to expand south and gain access to the Mediterranean. So in 1905, this affection for Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s ramshackle empire on the part of O’Conor and Sykes was also a reflection of Britain’s longstanding foreign policy.

When Sykes made his telephone call to Sir Nicholas, the ambassador was ensconced aboard his yacht anchored in the Golden Horn, his preferred place of residence. However, in due course he received Sykes’s message and shortly afterwards asked the attaché to join him for dinner. After the meal Sykes was invited to outline the contents of the small notebook he had obtained from the German engineer and which he had

meanwhile written up as a detailed memorandum. The ambassador was impressed and the following day, 15 October 1905, he dispatched Sykes’s document to the Foreign Office, with a covering note of his own and marked ‘SECRET’.

1

Ten days later, Mr Richard P. Maxwell, senior clerk in the Commercial Department of the Foreign Office, selected a dossier from the pile upon his desk and read the following:

SECRET. From H.M. Ambassador in Constantinople. ‘Report on the Petroliferous Districts of the Vilayets of Baghdad, Mosul and Bitlis; prepared by Sir Mark Sykes, Hon. Attaché.

The following accounts of the various Petroleum springs and asphalt deposits have been compiled from a report made to the Imperial Ottoman Government by an Engineer dispatched to the above mentioned Vilayets in 1901. The large map shows the distribution of the springs and deposits, the red Roman Numerals corresponding with the numbers scheduled in the following order. Where obtainable a large scale sketch has been appended to the verbal description showing the nature of the locality described.

2

Maxwell ploughed on,

No. I, Bohtan. 30 Kilometres up the Bohtan river … No. II Sairt … No. III Zakho … No. VI Baba Gurgur … The Petroleum Springs of Baba Gurgur are among the richest and most workable in the Vilayet of Mosul. They are situated in the vicinity of Kirkuk, being about 6 miles from the town at the foot of the Shuan Hills. They cover an area of about half a hectare and owing to the great heat are constantly burning, the petroleum in this zone seems limited to an area of 25 hectares, but still the deposits [are] of great promise.

3

There followed descriptions of a further nine petroleum deposits, at the end of which the author had made the suggestion that they ‘could be worked by means of pipelines leading from the springs to the sea’.

However, in a rather complacent letter to the ambassador of 25 October also classified ‘SECRET’, Maxwell merely commented that

printing the report with or without the maps … ‘was hardly worthwhile, although it might be shown to D’Arcy if he would call to see it’. (William Knox D’Arcy’s company was currently exploring for oil in southern Persia.) Finally, the Foreign Office official added that Sykes ‘might be thanked for the trouble he has taken’.

4

In Istanbul Sir Nicholas must have read the reply with some irritation. This was not the first occasion on which the embassy had informed the Foreign Office about the existence of potentially rich oil deposits in northern Iraq. A year earlier, with rumours circulating that the sultan had recently awarded an oil concession to the German company planning to build the railway to Baghdad, he had sent the foreign secretary, the Marques of Lansdowne, a map of the oil-bearing districts obtained by the embassy secretary, also from German sources.