Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (15 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Familial combined hyperlipidaemia

is associated with obesity or glucose intolerance and may be expressed as type IIa, IIb or IV hyperlipidaemia (see

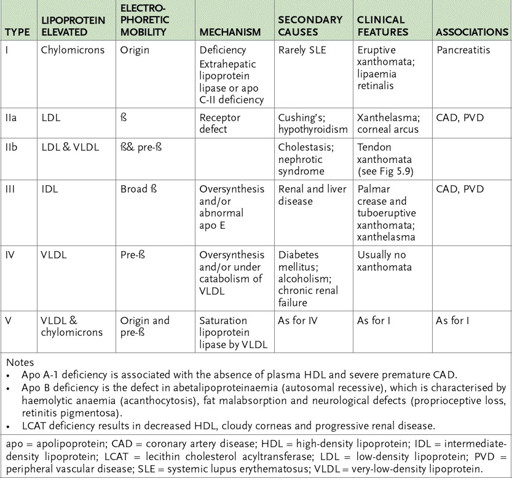

Table 5.3

). This is also an autosomal dominant trait. Patients develop hypercholesterolaemia and often hypertriglyceridaemia in puberty. Once again, there usually is a strong family history of premature coronary artery disease. There is no doubt that an elevated triglyceride level adds to the risk of hypercholesterolaemia.

Table 5.3

Hyperlipoproteinaemias

Familial dysbetalipoproteinaemia

is also associated with coronary artery disease. These patients have elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels and are usually found to have obesity, hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus. Find out whether there is any history of these and whether there has been atheromatous disease or vascular disease involving the internal carotid arteries and the abdominal aorta or its branches. Ask about claudication, which occurs in about one-third of patients.

2.

The patient may be able to tell you his or her cholesterol and triglyceride levels and what they have been in the past. Some patients even know their LDL and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels.

3.

If there is no history of coronary artery disease and the patient either knows the triglyceride level to have been very high or has a history of pancreatitis, the likely diagnosis is

familial hypertriglyceridaemia

. This is also a common autosomal dominant disorder and is associated with obesity, hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinaemia, hypertension and hyperuricaemia. Although there is a slightly increased incidence of atherosclerosis, this is probably related to diabetes mellitus, obesity and hypertension than to the hypertriglyceridaemia itself.

Ask about the patient’s alcohol consumption, any history of hypothyroidism or the ingestion of oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives. Any of these can precipitate a rapid rise in the triglyceride level, which may precipitate pancreatitis or the characteristic eruptive xanthomas. Between attacks, patients have moderate elevations of the plasma triglyceride level.

4.

Next, find out about treatment. In familial hypercholesterolaemia, this will have been aimed at the cholesterol level itself and at any cardiovascular complications that have

occurred. The patient should be well informed about a low saturated fat diet and may be aware of side-effects from medication usage.

5.

The need for drug treatment of hyperlipidaemia depends on the lipid levels and on the patient’s other vascular risk factors. Ask about a family history of premature coronary disease (first-degree relatives under the age of 60), previous vascular disease (coronary, cerebral or peripheral), smoking and diabetes mellitus.

6.

Ask about any history of cutaneous xanthoma. These may have resolved with treatment or been surgically removed.

The examination

1.

Examine the cardiovascular system. There may be evidence of cardiac failure from previous myocardial infarcts or a sternotomy scar from previous coronary surgery. Occasionally one sees the scandalous situation of a patient with untreated hyperlipidaemia presenting with more angina after initially successful coronary surgery.

2.

Look specifically for the interesting skin manifestations of these conditions.

a.

Patients with the heterozygous or homozygous form of familial hypercholesterolaemia may have

tendon xanthomas

. These are nodular swellings that tend to involve the tendons of the knee, elbow and dorsum of the hand and the Achilles tendon. They consist of massive deposits of cholesterol, probably derived from the deposition of LDL particles. They contain both amorphous extracellular deposits and vacuoles within macrophages, and sometimes become inflamed and cause tendonitis.

b.

Cholesterol deposits in the soft tissue of the eyelid cause

xanthelasma

and those in the cornea produce

arcus cornea

(previously insensitively called

arcus senilis

).

Xanthelasma occur in about 1% of the population and arcus cornea in 30% of people over 50. When corneal arcus is seen in younger people it is more often associated with hyperlipidaemia. Surveys of people with xanthelasma indicate a slightly higher than average cholesterol level. Tendon xanthomas are diagnostic of familial hypercholesterolaemia, but the other signs are not as specific – only 50% of people affected have hyperlipidaemia.

The majority of patients with the homozygous form have even more interesting signs.

•

Yellow xanthomas may occur at points of trauma and in the webs of the fingers.

•

Cholesterol deposits in the aortic valve may be sufficient to cause aortic stenosis; occasionally mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation can occur for the same reason.

•

Painful swollen joints may also be present. Obesity is uncommon in these patients.

c.

These skin manifestations may or may not resolve with treatment of the cholesterol level. Surgical treatment is sometimes indicated.

d.

Eruptive xanthomas are a sign of hypertriglyceridaemia (levels often over 20 mmol/L). This is type V hyperlipoproteinaemia. Eruptive xanthomas occur on pressure areas, such as the elbows and buttocks, and resolve rapidly with treatment. The association here is with pancreatitis. The problem is often hereditary, but exacerbated with obesity, diabetes and alcohol consumption. It is a less definite risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Palmar xanthomata are a sign of dysbetalipoproteinaemia (type III hyperlipoproteinaemia). They also resolve with treatment.

3.

If the history suggests combined hyperlipidaemia or hypertriglyceridaemia, obesity is likely to be present. Look also for signs of the complications of diabetes mellitus and for signs of hypothyroidism or the nephrotic syndrome (see

Table 11.2

).

4.

In sick patients with hypertriglyceridaemia, there may be signs of acute pancreatitis.

Investigations

1.

A cholesterol level over 8 mmol/L with a normal triglyceride level suggests one of the familial hyperlipidaemias. This diagnosis can be confirmed by an assay of the number of LDL receptors on blood lymphocytes. The diagnosis is more often made from a combination of the lipid pattern, the history and the clinical examination (see

Table 5.3

). The other necessary investigations are those required for coronary artery disease.

2.

Investigation of hypertriglyceridaemia includes tests to exclude possible underlying causes, such as hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus and excessive alcohol intake. In familial hypertriglyceridaemia the plasma triglyceride level tends to be moderately elevated to 3–6 mmol/L (type IV lipoprotein pattern). The cholesterol level is normal. The triglyceride level may rise to values in excess of 12 mmol/L during exacerbations of the condition.

3.

Familial combined hyperlipidaemia produces one of three different lipoprotein patterns – hypercholesterolaemia (type IIa), hypertriglyceridaemia (type IV), or both hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia (type V).

4.

Familial dysbetalipoproteinaemia (type III hyperlipoproteinaemia) results in the accumulation of large lipoprotein particles containing triglycerides and cholesterol. These particles resemble the remnants and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) particles normally produced from the catabolism of chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). These patients are homozygous for the apolipoprotein E2 (apo-E2) allele, which is unable to bind to hepatic lipoprotein receptors, thus

preventing the rapid hepatic uptake of IDL and chylomicrons. The condition is usually expressed only in patients with hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus and tests for these disorders are necessary. Apo-E genotyping may sometimes be useful.

Management

1.

A combination of diet and treatment of the underlying condition is usually required. Underlying diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism must be treated.

2.

Some patients with dysbetalipoproteinaemia respond dramatically to the introduction of thyroxine. Effective management of the condition tends to cause disappearance of the skin signs and improves the prognosis as far as vascular disease goes. Effective treatment of familial hyperlipidaemia from early adult life delays the onset of coronary artery disease.

3.

Treatment is almost always begun with hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins, e.g. pravastatin, lovastatin, artorvastatin, rosuvastatin). Except for artorvastatin, these drugs should be taken at night. They are relatively short acting and most cholesterol is manufactured at night. They work by inhibiting the synthesis of cholesterol in the liver by impeding the activity of the rate-limiting enzyme. Patients need to have their liver function checked after about a month. They are effective drugs; total cholesterol levels may be expected to fall at least 30%.

a.

The Four-S trial in Scandinavia was the first of a number of trials to show a definite survival advantage for patients treated with these drugs for secondary prevention (i.e. those patients who have already had an ischaemic event). Secondary prevention trials for high- and intermediate-risk patients have also been positive. It is now clear that patients with existing coronary artery disease or multiple risk factors benefit most from lipid-lowering treatment. Previous concern about an apparent increase in overall mortality associated with lipid lowering seems to have been allayed.

b.

The current indications for drug treatment of cholesterol allow a statin for patients with established symptomatic coronary artery disease at any total cholesterol level.

c.

The most frequent problem with these drugs is the occurrence of myalgias. These are, however, uncommon. The relatively long experience with the statins suggests they are safe in quite large doses and current starting doses are two to four times those used in the past. Artorvastatin and rosuvastatin are the most potent statins and should be the drugs of choice for severe hypercholesterolaemia. All the statins favourably affect the HDL/LDL ratio.

d.

There is controversy about the need to treat levels that are already below 4 mmol/L. There is evidence that there are pleotrophic effects of the statins that reduce coronary risk separately from their effect on cholesterol. This also implies that, for secondary prevention, the use of statins may be beneficial for patients whose total cholesterol is below 4 mmol/L before drug treatment.

4.

Ezetimibe reduces cholesterol absorption from the gut and thus interrupts its enterohepatic circulation. It does not seem to interfere with the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Its effect on cholesterol levels is substantial, although not as great as that of the statins. It is useful for patients who are intolerant of the statins or, when used in combination with a statin, for patients whose cholesterol level is not controlled on a statin alone.

5.

Gemfibrozil increases the activity of lipoprotein lipase and is useful in hypertriglyceridaemia resulting from increased VLDL or IDL levels. Its main use is for patients with elevation of both cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Clofibrate is no longer in common use for lipid control.

6.

A few patients may be taking one of the bile-sequestering resins – cholestyramine or colestipol. These are less often used as initial treatment now that the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are generally available. Some patients may use a statin and a resin in combination. Resins bind bile salts in the gut so that cholesterol is withdrawn from the circulation by the liver to make more. They are not absorbed, but can cause constipation and flatulence and can block the absorption of other drugs. Patients may need to take up to two sachets (8 g) three times daily.

7.

If the cholesterol cannot be brought down to normal levels with diet and a resin, nicotinic acid (which blocks VLDL synthesis) can be added. This is an effective drug and may help block the compensating increase in hepatic cholesterol synthesis that occurs with bile-sequestering resins. It is also used to try to raise HDL levels. Side-effects include flushing, pruritus, abnormal liver function tests, hyperglycaemia and aggravation of peptic ulcer disease. The patient will probably have been begun on a small dose and had this gradually increased as tolerance improved. In practice it is a very difficult drug to use because of its side-effects.

8.

A patient with one of the combined hyperlipidaemias is likely to need to lose weight, as well as to control the cholesterol and saturated fat intake, and with dysbetalipoproteinaemia may require treatment for hypothyroidism. All these patients need to avoid alcohol and oral contraceptives. Diet is the mainstay of treatment for reducing triglyceride levels; gemfibrozil or one of the newer fibrates may be used if diet fails.

9.

The indications for treatment of hyperlipidaemia with drugs on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) are complicated. Total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglyceride levels, as well as the presence of other risk factors, are all part of the formula. Candidates should be familiar with the latest PBS rules.