Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (19 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

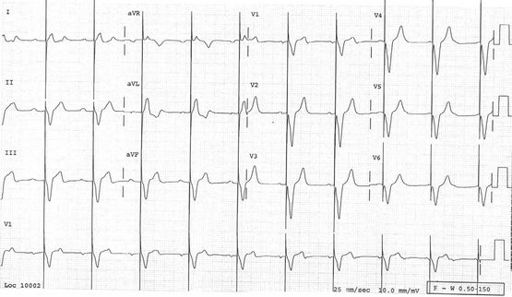

FIGURE 5.16

Sinus rhythm in WPW conduction. The delta waves and overall QRS are directed anteriorly in V1, superficially resembling RBBB. This is type A WPW where the bundle of Kent inserts into the left ventricular myocardium. Where the delta wave is initially isoelectric, the PR interval appears normal. Note also the close resemblance to an inferoposterior infarction.

8.

recent alcoholic binge

9.

pulmonary embolism

10.

thyrotoxicosis.

Ask whether the rhythm has been paroxysmal and self-limiting, persistent and requiring cardioversion, or permanent.

Find out about treatment.

1.

Has the patient required intravenous drugs to control the heart? Have these been by infusion or bolus injection? Intravenous adenosine is now the drug treatment of first choice for SVT. Patients may well remember its use. It causes a brief but distressing sensation of impending death.

2.

Have physical manoeuvres been tried?

3.

What oral drugs have been used in the past and during this admission? Make enquiries about the known side-effects of these drugs.

4.

The investigations the patient has undergone or may be about to undergo can help sort out the diagnosis.

a.

Certain tests, such as electrophysiological studies (EPS), are more memorable than others. An EPS with induction of VT may mean that direct current (DC) cardioversion was required; despite sedation and reduced cardiac output, some memory of this may remain.

b.

A cardiac biopsy may have been performed to look for right ventricular cardiomyopathy (RV dyplasia), a cause of VT.

c.

Cardiac MRI and CT scans are commonly used to look for the patchy changes of cardiac sarcoid or right ventricular (RV) cardiomyopathy (RV dysplasia).

d.

Other procedures may have been entirely therapeutic: for example, DC cardioversion performed electively under general anaesthesia suggests AF or atrial flutter; catheter ablation, often a fairly prolonged procedure, suggests SVT or VT; pacemaker insertion suggests bradycardia; antiarrhythmia surgery suggests VT or, less often now, SVT.

5.

Catheter ablation is now a routine treatment for SVT that does not respond to simple drug treatment. Rarely there may be failure to suppress the arrhythmia, or a complication such as complete heart block or cardiac rupture can occur. Ablation is also very effective for some forms of VT. These include right, and the less common left, ventricular outflow tract tachycardias. These benign forms of VT can cause frequent recurrent episodes of self-limiting VT with a left or right bundle branch block morphology, respectively. They may respond to treatment with verapamil but are otherwise managed with catheter ablation.

6.

Patients with automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (AICDs) can often provide vast amounts of useful information about their devices and about their arrhythmia.

The examination

Examine the cardiovascular system. Is the patient in sinus rhythm clinically? Look for thoracotomy scars, pacemakers and implanted defibrillators. Look for signs of cardiac failure, valvular heart disease and evidence of recent abdominal surgery or thyrotoxicosis.

Investigations

These depend on the actual rhythm problem.

1.

Resting ECG

. Look for:

a.

the current rhythm

b.

evidence of pre-excitation (Wolff-Parkinson-White conduction – see

Fig 5.16

; Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome)

c.

heart block

d.

old infarct

e.

paced rhythm (ventricular-ventricular inhibited (VVI) or dual chamber atrial sensing and ventricular pacing or dual-chamber pacing)

f.

long QT interval (increased risk of polymorphic VT –

torsade de pointes

).

2.

The examiners may produce previous ECGs or parts of 24-hour Holter monitors

. Remember that a broad, complex tachycardia should be considered VT unless there is good reason to consider otherwise. There are a number of ECG criteria for distinguishing VT from SVT with aberrant conduction.

Findings suggestive of VT include:

a.

QRS >0.14 seconds (if a RBBB pattern) or >0.16 seconds (if a LBBB pattern)

b.

left-axis deviation (between −90° and −180°)

c.

atrioventricular (AV) dissociation (with P waves ‘marching through’ the QRS complexes)

d.

changes from the pre-existing QRS morphology in pre-existing bundle branch block (but note, these rules do not apply in SVT with aberration caused by WPW conduction).

The presence of known ischaemic heart disease, or cardiac failure, is particularly useful.

Broad complex tachycardia in a patient with ischaemic heart disease is usually VT

(95%).

3.

EPS

may be used to assess inducibility of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias before and after treatment. It is now used in conjunction with catheter ablation as curative treatment for SVT caused by accessory pathways and for some types of VT. It can also be performed to ablate the AV node or the regions around the four pulmonary veins for patients with intractable and disabling AF. Ablation treatment has an increasing role for the management of ischaemic and non-ischaemic VT, usually in conjunction with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator.

4.

Routine investigations for patients with AF

include echocardiography, thyroid function testing and sometimes exercise testing. Echocardiography may reveal an underlying pathology that is responsible for the AF (e.g. mitral stenosis). It is important in helping quantify embolic risk. Look at the echo for:

a.

valve abnormalities

b.

cardiomyopathy

c.

diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (especially important in hypertensive patients)

d.

left ventricular hypertrophy

e.

atrial size (consider atrial septal defect)

f.

mitral valve disease

g.

segmental wall abnormalities consistent with ischaemic heart disease.

Tests may be needed because of actual or potential drug side-effects (e.g. liver function or thyroid function tests for patients on amiodarone).

5.

Cardiac catheterisation

is often indicated for patients with ventricular arrhythmias, as they may have an ischaemic substrate. Patients whose VT has been stable but becomes unstable (often leading to more activity on the part of their cardioverter defibrillator) may have developed new ischaemia and should have this possibility investigated and treated.

Management

Much depends on the rhythm abnormality.

1.

Arrhythmias that are not life-threatening are usually managed, at least at first, with drugs. Candidates will be expected to have a thorough working knowledge of the common antiarrhythmic drugs, their methods of action, indications and side-effects. Remember that many antiarrhythmic drugs have a potentially dangerous proarrhythmic effect.

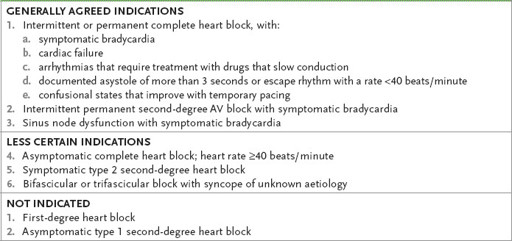

2.

The indications for permanent pacing (

Table 5.9

) and different uses for VVI, VVIR (rate-responsive) and DDD (dual-chamber) pacers (

Figs 5.17

and

5.18

) should be well understood. A basic understanding of antitachycardia devices and indications for their use (see

Table 5.10

) is also important.

Table 5.9

Indications for permanent pacemaker insertion in adults

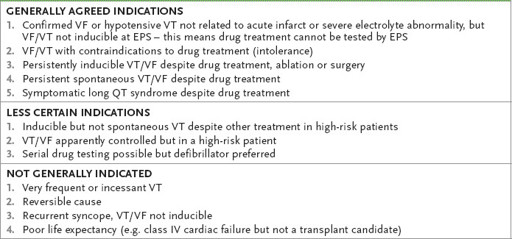

Table 5.10

Indications for implanted cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs)

Note:

Increasingly proven VT or VF in a patient with poor LV function is considered an indication regardless of EPS findings.

VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = ventricular tachycardia; EPS = electrophysical study.

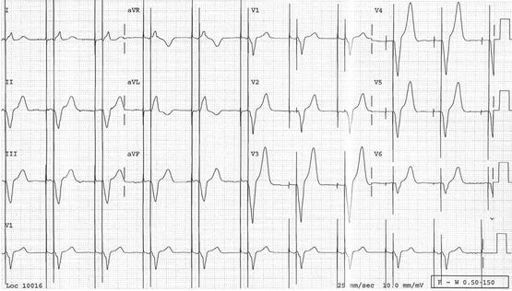

FIGURE 5.17

Atrial sensing and ventricular pacing. This is the ECG of a patient with a dual-chamber pacemaker. Normal P waves are followed by an atrioventricular (PR) interval and then a pacing spike, which precedes a wide QRS complex with a LBBB pattern (pacing is from the right ventricular apex).

FIGURE 5.18

Dual-chamber pacing. Pacing spikes precede both atrial and ventricular complexes.

3.

Automatic implanted cardioverter-defibrillators (AICDs) are increasingly used to manage recurrent VT.

•

They are often used in combination with antiarrhythmic drugs of some sort. They are becoming smaller, cheaper (between $25,000 and $40,000) and more complicated. It is now established that they improve mortality rates in selected patients.

•

They are usually the treatment of choice for hypotensive VT or missed sudden death from VF. Drug treatment of these conditions is not very effective.

•

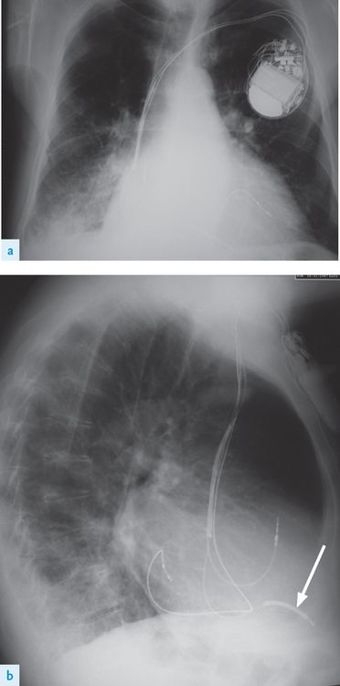

The current models have leads that can be placed intravenously into the vena cava and for pacing purposes into the right ventricle.

•

They are small enough to be implanted like pacemakers in the chest wall, but are still noticeably larger than pacemakers (

Fig 5.19

). Implantation takes place under local anaesthetic in the electrophysiology laboratory.