Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (14 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

1.

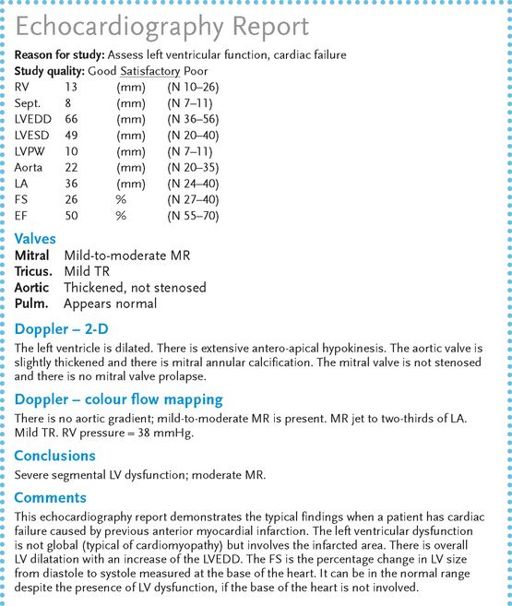

Echocardiography

(

Fig 5.8

). This will show generalised or segmental wall motion abnormalities and reduced fractional shortening. An estimate of the left ventricular ejection fraction can be made. Segmental hypokinesia suggests that ischaemia is the

cause of the cardiac failure. Doppler echocardiography will usually show at least some mitral and tricuspid regurgitation in these patients. The presence of more severe valvular disease suggests a different aetiology for the cardiac failure. Serial echocardiograph measurements of left and right ventricular dimensions can be useful for following the patient’s progress.

FIGURE 5.8

Echocardiography report in a patient with cardiac failure caused by anterior myocardial infarction.

FIGURE 5.9

(a) Achilles tendon xanthoma. (b) Xanthelasma. (c) Palmar xanthoma. (d) Eruptive xanthomas. (a) courtesy A F Lant, J Dequeker, London; (b) M Yanoff, J Duker.

Opthamology

. 3rd edn. Fig 12-9-18. Mosby, Elsevier, 2009, with permission; (c) and (d) courtesy R A Marsden, St George’s Hospital, London.

2.

A gated blood pool scan for the ejection fraction

. The right ventricular ejection fraction is normally >45% and the left ventricular ejection fraction is >50%. The scan will also show whether hypokinesis is global or segmental and to what extent the right ventricle is affected.

3.

Coronary angiography

. This is often necessary to exclude coronary artery disease.

4.

Right ventricular biopsy

. This may help determine the aetiology in selected patients.

Treatment

1.

Remove precipitating causes. Atrial fibrillation and other incessant tachycardias can be a cause of cardiac failure – tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. The prognosis is good if normal heart rate can be restored.

2.

Correct underlying causes if possible (e.g. thrombolysis for an acute infarct or coronary artery bypass grafting or angioplasty for ischaemia) (see

Table 5.2

).

Table 5.2

Causes of ventricular failure

3.

Control the failure.

a.

Decrease physical activity (e.g. bed rest for the acutely ill patient).

b.

Control fluid retention (e.g. by diuretics, low-salt diet, fluid restriction (1000–1500 mL for severe failure)).

•

Patients should be advised to weigh themselves daily. An increase in weight of 2 kg or more over a few days is usually an indication of significant fluid retention. A temporary increase in the diuretic dose will often prevent a deterioration in symptoms.

c.

Oppose inappropriate activation of the renin–angiotensin system.

•

ACE inhibitors are considered to be the drug class of choice for cardiac failure as they prolong life; symptomatic hypotension is the major side-effect in cardiac failure. ACE inhibitors are indicated for all classes of heart failure, even for asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Every effort should be made to titrate the dose up to the maximum tolerated. The usual limitation is symptomatic hypotension.

•

AR blockers are indicated for patients intolerant (usually because of cough) of ACE inhibitors. The most common reason for the cessation of ACE inhibitors or AR blockers is deterioration in renal function (usually in patients with renovascular disease).

•

Renal function may improve again if the ACE inhibitor and diuretic doses are reduced and hypovolaemia is corrected. There is little therapeutic difference between the various ACE inhibitors.

•

Trials have also demonstrated some additional benefit when ACE inhibitors and AR blockers are combined. The treatment of cardiac failure involves polypharmacy. It is probably only the minority of patients who will be prepared to take an AR blocker, as well as all the other drugs usually prescribed. The combination also seems to increase the risk of acute renal failure and is rarely used.

•

Add spironolactone. This aldosterone antagonist improves survival in class III or IV patients. It may be especially useful for the management of ascites and peripheral oedema. Hyperkalaemia may be a problem for patients with renal impairment. Start with 12.5 mg per day. Epleronone is a newer aldosterone antagonist indicated for heart failure occurring soon after myocardial infarction.

•

Asking the patient about the difficulties of adherence with a complicated drug regimen may be useful at this point.

d.

Oppose inappropriate increases in catecholamine drive.

•

Give beta-blockers. Trials with carvedilol, bisoprolol and extended-release metoprolol have shown improvements in symptoms and mortality for this drug used in patients with class II–IV heart failure.

•

The drugs must be introduced at a low dose (e.g. 3.125 or 6.25 mg b.d. of carvedilol or 1.25 mg daily of bisoprolol) and titrated upwards as tolerated to 25 mg b.d. of carvedilol or 10 mg daily of bisoprolol.

e.

Increase myocardial contractility (e.g. with digoxin).

Note:

The use of digoxin in cardiac failure is again controversial. Recent trials have suggested an increase in symptoms if cardiac failure patients who are in sinus rhythm and on treatment with digoxin, diuretics and ACE inhibitors have their digoxin withdrawn. Re-assessment of digoxin mortality trials have suggested a possible increase in mortality. Patients most likely to benefit symptomatically have more severe heart failure, an S3 gallop, impressive cardiomegaly and an ejection fraction <20%.

f.

Intravenous inotropes (e.g. dopamine or dobutamine) may have a place in the short-term treatment of severe cardiac failure. Patients may be admitted for a ‘dobutamine holiday’ (a course of treatment with intravenous dobutamine, usually for about 5 days) and have improved symptoms for some months. Levosimendan is an intravenous drug that works as a calcium channel activator. A 24-hour course may improve symptoms and possibly prognosis. No effective oral inotrope is available.

g.

Control rhythm. Remember, cardiac failure has a poor prognosis. About 50% of these patients die suddenly of a ventricular arrhythmia. The detection of high-grade ventricular arrhythmias is an indication for an

implanted defibrillator

, which is associated with a proven improvement in prognosis. Routine use of these devices in patients with a low ejection fraction has been shown to improve survival, even when ventricular arrhythmias have not been recorded.

h.

Cardiac transplantation may now be offered to certain patients. The reduced availability of donor hearts and the improvement of many patients who would otherwise be suitable for transplant with beta-blockers have reduced the frequency of this procedure.

i.

Biventricular pacing or cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) is helpful for heart failure patients with very wide QRS complexes. The LV pacing wire is placed via the coronary sinus into one of the left ventricular veins. This complicated procedure enables both ventricles to be paced and dyssynchronous contraction of the ventricles associated with a very wide QRS to be corrected. About 70% of patients improve with the treatment. Although echocardiographic measurements of dyssynchrony are available, they have not yet been able to predict a response to resynchronisation treatment and the current guidelines allow their use for symptomatic patients with LBBB.

j.

Ventricular assist devices are sometimes used as a bridge to transplant in very ill patients. Survival for weeks or months is possible with these devices. Trials of entirely artificial hearts continue in small numbers of patients.

Diastolic heart failure (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction)

Most breathless patients with heart failure have abnormal left ventricular systolic function, which is characterised by dilatation and hypokinesis. Some cases of cardiac

failure, however, may be caused by diastolic dysfunction. In such cases, the myocardium is stiff, often because it is hypertrophied and does not relax normally. The condition seems to be more common in elderly patients. Hypertension is a common cause. The diagnosis is difficult, but an echocardiogram will show preserved or increased systolic contraction without dilatation and there may be left ventricular hypertrophy and left atrial dilatation. Doppler echocardiography may show abnormalities of left ventricular filling caused by the stiffness of the ventricle. However, this is not easy to quantify and is dependent on variations in preload and afterload.

The condition may have a prognosis as bad as that of systolic heart failure. Treatment is similar, but beta-blockers are used early and only small doses of diuretics should be required. At least in theory, digoxin should be avoided if the patient is in sinus rhythm. Every effort should be made to control hypertension. Treatment has not been shown to alter prognosis.

Hyperlipidaemia

Hyperlipidaemia may be present in patients under investigation for vascular disease, pancreatitis, hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus. It often presents both diagnostic and management problems.

The history

1.

The patient should be able to indicate whether the main problem is vascular or not. If the problem is one of premature coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolaemia is the likely lipid problem. The most important inherited cause is

familial hypercholesterolaemia

, which is caused by a defective or absent low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor. The heterozygous form occurs in about one person in 500. As the transmission is autosomal dominant, the patient may know of first-degree relatives who have been affected. There may even be family members with the homozygous form. These people usually present with a tenfold elevation in serum cholesterol levels as a result of an increase in plasma LDL levels and have a myocardial infarction before the age of 20 years. People with the heterozygous form typically have myocardial infarctions in their 30s and 40s and have a two- to threefold elevation in cholesterol level. More than 80% of affected men and nearly 60% of affected women have had myocardial infarcts by the age of 60 years. Find out whether the patient has already had a myocardial infarct and which relatives have been affected.