Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (18 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

These depend somewhat on the reason the patient has been admitted to hospital on this occasion.

1.

Endomyocardial biopsies are performed routinely and at any suggestion of rejection. Ask about the results of these biopsies.

2.

A full blood count (FBC) may be indicated because of possible infection and to monitor the azathioprine dose.

3.

Chest X-ray may show signs of cardiac enlargement, although this is a late sign of rejection. Changes of rejection on the ECG include a reduction in voltage caused by myocardial oedema or atrial arrhythmias. Sometimes the patient’s ECG shows two sets of P waves: one comes from the transplanted heart and one arises from the residual atrium.

4.

Recent assessments of myocardial function, including gated blood pool scans and resting or stress echocardiograms, may be available.

5.

Routine coronary angiography may have been performed.

6.

If there have been problems with possible infection, results of blood, urine and other cultures should be sought.

Management

The discussion should revolve around the patient’s current problem or reason for admission. However, there is likely to be time to discuss the management of rejection, infection, cardiac failure or social problems.

1.

Rejection may have been suspected because of pleuritic chest pain, deterioration in left ventricular function or ECG changes. It is diagnosed on the basis of a routine biopsy. The usual approach is to give the patient a boost of methylprednisolone – usually 1 g intravenously daily for 3 days, followed by a repeat biopsy.

2.

Infections occurring as a result of immunosuppression are a major cause of death. Possible episodes of infection should be investigated thoroughly and treated aggressively with appropriate therapy. Opportunistic infections are relatively common as a late complication. Cytomegalovirus, herpes,

Pneumocystis jirovecii

, fungal infection, and

Nocardia

and

Toxoplasma

are all more common than in non-immunosuppressed people.

3.

Further cardiac failure may be an indication of rejection, which should be treated. Cardiac failure may also be an indication of silent myocardial infarction.

4.

Hyperlipidaemia should be sought routinely and treated most vigorously with drugs and diet.

There may be discussion about the patient’s prognosis. The 1-year survival rate after transplant is about 90% and the 5-year survival rate is about 75%. The 10-year survival rate approaches 50%.

The discussion of a patient awaiting cardiac transplantation will probably run along similar lines. However, it is important to know how well informed the patient is about what is likely to happen, whether he or she appears to fulfil the criteria for transplantation (see

Table 5.7

) and whether there appear to be any contraindications. Some patients awaiting transplantation are sick enough to require intravenous inotropes. There may even have been talk about the use of external circulatory assistance devices for use as a bridge to transplant.

Cardiac arrhythmias

The management of some cardiac rhythm disturbances is complicated. These patients may be in hospital while waiting for diagnostic tests or, in cases of serious arrhythmias, for treatment to become effective.

They sometimes represent diagnostic, but more often management, problems. Ventricular arrhythmias are a more common reason for admission than supraventricular arrhythmias, but patients with the latter may be awaiting diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Atrial fibrillation, the most common of the significant cardiac arrhythmias, is unlikely to be the patient’s only problem if it appears in a long case.

The history

Ask why the patient is in hospital – all may be revealed without much further effort. Otherwise, the patient may know the name of the arrhythmia or be able to describe symptoms that make the diagnosis likely. If the rhythm problem is a serious and continuing one, the candidate may be fortunate enough to find the patient on an ECG monitor.

Possible presenting symptoms include:

1.

rapid and irregular palpitations – suggest atrial fibrillation (AF) (

Fig 5.11

)

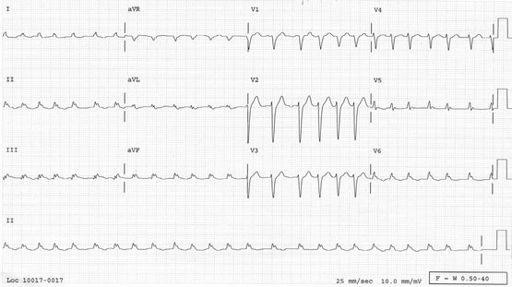

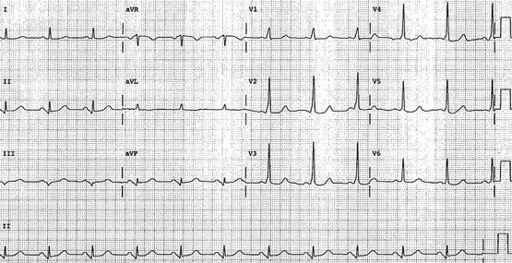

FIGURE 5.11

Atrial fibrillation. The ventricular response rate is rapid – between 95 and 160 beats/minute.

2.

rapid and regular palpitations, with or without dizziness and perhaps terminated by Valsalva manoeuvres – suggest supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) (

Fig 5.12

)

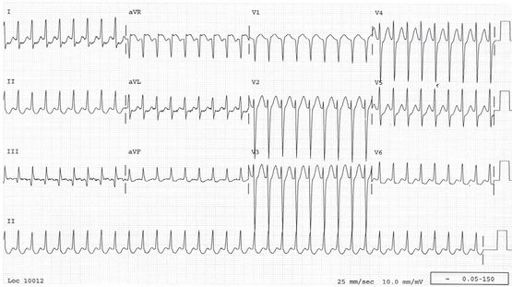

FIGURE 5.12

Supraventricular tachycardia. The complexes are narrow. The heart rate is about 200 beats/minute and the rhythm is regular.

3.

rapid and regular palpitations with dizziness, syncope or near syncope – suggest ventricular tachycardia (VT),

particularly if there is a history of ischaemic heart disease

4.

syncope with bradycardia or no palpitations – suggests heart block (

Fig 5.13

)

FIGURE 5.13

Sinus rhythm. First-degree heart block, right bundle branch block (RBBB) and left anterior hemi-block (LAHB). This combination of abnormalities is called

trifascicular block

. It is a sign of significant conduction system disease and, in a patient with recurrent syncope, suggests that intermittent complete heart block may be the cause of the symptoms.

5.

symptoms of AF and episodes of syncope – suggest sick sinus syndrome

6.

a family history of sudden death – suggests the possibility of congenital long or short QT interval (

Fig 5.14

), Brugada syndrome (ionopathy) or a structural cardiac problem such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

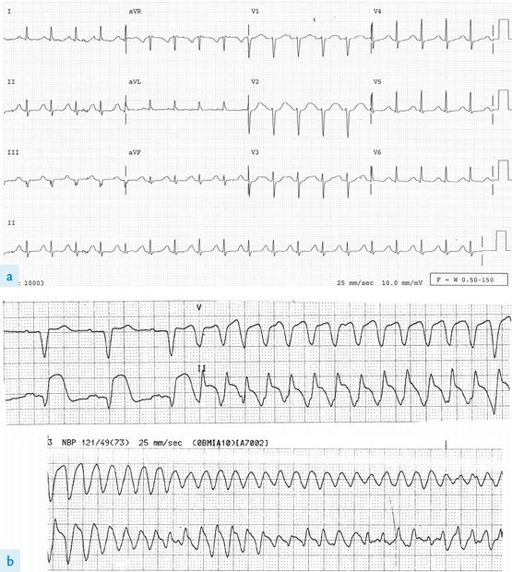

FIGURE 5.14

(a) Sinus rhythm. The QT interval is prolonged (423 ms) and the corrected QT (QTc) is 460 ms (normal <440 ms). These patients are at risk of syncope or sudden death as a result of the development of polymorphic VT. (b) Polymorphic VT or torsade de pointes. This apparent twisting of the QRS complexes is named after the gold braid on French military uniforms.

7.

the occurrence of syncope in association with antiarrhythmic drug treatment suggests the possibility of proarrhythmia; ask about class 1C drugs and sotalol, perhaps prescribed because of paroxysmal AF, as these drugs may also worsen bradyarrhythmias in patients with sick sinus syndrome.

Ask about previous known heart disease (e.g. ischaemic heart disease and VT, aortic stenosis and heart block) and recent cardiac, thoracic or abdominal surgery.

•

Cardiac surgery may be complicated by heart block and all of the above may precipitate AF.

•

The ‘grown-up’ congenital heart disease patient may have persisting problems with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias following cardiac surgery in childhood.

•

Atrial septal defects are often complicated by atrial arrhythmias even after they have been repaired.

•

Consider the common causes and associations of AF:

1.

advancing age (3% of 65-year-olds, >6% of people in their 80s)

2.

hypertension

3.

mitral valve disease

4.

ischaemic heart disease and myocardial infarction

5.

recent thoracic or abdominal surgery

6.

atrial septal defect

7.

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome (see

Figs 5.15

and

5.16

)

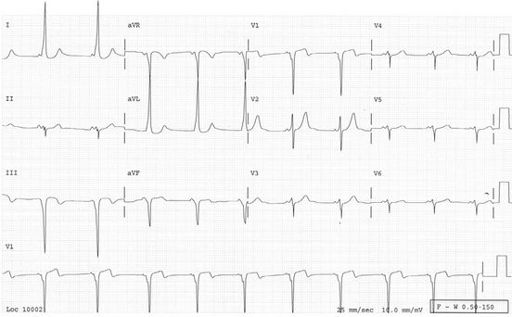

FIGURE 5.15

Sinus rhythm. Wolff-Parkinson-White conduction. The PR interval is short and delta waves are visible. There are positive delta waves in lead I – seen as a slurred upstroke at the start of the R wave – and negative delta waves in lead III – seen as a slurred Q wave. These patients’ ECGs are usually abnormal between their attacks of tachycardia but the

pre-excitation

(delta wave) may occur only intermittently. They are at risk of sudden death or syncope if atrial fibrillation or flutter occurs (they are often at increased risk of this arrhythmia) because very rapid ventricular rates may occur if the accessory pathway can conduct at high rates. Treat acute atrial fibrillation or flutter in this setting if unstable using electrical cardioversion (never use verapamil, adenosine or digoxin).