Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (17 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

•

known contraindications to a class of drugs (e.g. renal artery stenosis and ACE inhibitors)

•

convenience of drug regimen (e.g. once-daily dosage)

•

interaction with other medications (e.g. concerns about bradycardia with betablockers and verapamil)

•

existing medical problems that favour the use of a class of drugs (e.g. cardiac failure and ACE inhibitors)

•

cost

•

possible additional protective effects of some antihypertensives (e.g. ACE inhibitors and patients who have had a stroke or have diabetes).

The current Heart Foundation recommendation is that treatment begin with a small dose of a single drug. Intolerance suggests the need to try a different class. The Foundation recommends that failure to achieve control should be managed with the addition of a small dose of another class of drug. The idea is to minimise side-effects. The disadvantage of this approach is that almost all patients will end up on multiple drugs, which can be a problem for compliance and cost. The other approach is to titrate up the dose of one drug to the maximum recommended, unless side-effects occur. Then a second drug from another class is added. Some drugs are especially effective in combination:

•

beta-blocker and dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist

•

ACE inhibitor or AR antagonist and thiazide

•

ACE inhibitor or AR antagonist and calcium antagonist

•

beta-blocker and alpha-blocker

•

beta-blocker and thiazide.

Fixed-dose combinations of two or even three of these are available: ACE inhibitor and thiazide, calcium antagonist and ACEI or ARB + or- diuretic, beta-blocker and alpha-blocker (labetolol). These combinations are not approved for the initiation of treatment. Candidates should be familiar with the doses of the common antihypertensive drugs and their important side-effects.

RENAL ARTERY DENERVATION

Catheter-based denervation of the renal artery can now be performed using radiofrequency energy or drug instillation. Early trials have shown significant – up to 20mmHg – and sustained reduction in blood pressure for the patients not controlled on four or five drugs. The treatment is still experimental.

Heart transplantation

Cardiac transplantation is now an accepted form of treatment for intractable cardiac failure. Numbers of patients who have either had a transplant or are on the waiting list for one are available for clinical examinations. Those awaiting transplantation are sick enough to require frequent admissions to hospital, and those who have had a transplant are often re-admitted for various routine investigations. Many patients who would once have required a transplant are now stable on treatment with betablockers and ACE inhibitors. Therefore patients on a transplant list tend to have severe heart failure which has not responded to medical treatment or resynchronisation pacing. Patients are usually well informed about their condition and should be able to supply a lot of useful information to the candidate.

Although this fact should not be discussed with our surgical colleagues, heart transplantation is technically not a very difficult operation. Improvements in prognosis have followed medical advances, particularly in the area of the management of rejection. The 5-year survival rate is now slightly more than 75% for patients who have received a transplant since 1981 and the 1-year survival rate is currently about 90%.

As in all transplantation long cases, the examiners will expect the candidate to be familiar with the indications for and contraindications to the procedure. It is also important to know what investigations are required before a patient can be accepted for surgery and to understand the management problems that can occur in patients who have had the operation (

Table 5.7

).

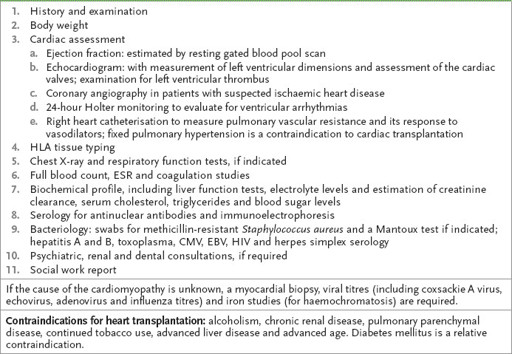

Table 5.7

Evaluation for heart transplantation

CMV = cytomegalovirus; EBV = Epstein-Barr virus; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HLA = human leucocyte antigen.

The history

1.

Try to establish the cause of the patient’s cardiac failure. In younger patients, cardiomyopathy is more likely to be the problem, but nearly half the patients currently undergoing heart transplantation have ischaemic heart disease. Rheumatic valvular heart disease can also affect younger patients. Combined heart and lung transplantation is occasionally carried out for patients with primary pulmonary hypertension or cystic fibrosis. It may also be the treatment of choice for some forms of congenital heart disease, either in childhood or adult life; if pulmonary hypertension is present, these patients have to be considered for combined heart and lung transplantation.

Ask about previous myocardial infarction or angina and whether the patient knows the results of cardiac catheterisation. All patients undergoing a transplant are required to have cardiac catheterisation. There may have been a preoperative cardiac biopsy performed and the patient may be aware of the results of this test. Also ask about previous thoracotomies.

2.

Ask about the patient’s symptoms before surgery. Obtain an idea of the exercise tolerance and the severity of angina, if present. The patient may know the results of investigations of cardiac function, such as exercise tests and gated blood pool scans, before and after surgery.

3.

Ask what treatment the patient was receiving before transplantation, particularly the doses of diuretics, ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers (e.g. carvedilol). Find out whether frequent admissions to hospital have been necessary and whether intravenous inotropes were required. There may have been recurrent ventricular arrhythmias before surgery. Treatment may have been with drugs, especially amiodarone or an implanted defibrillator and antitachycardia pacemaker and resynchronisation device. Some patients have undergone previous surgery for arrhythmias. This may include resection of an aneurysm or myocardial resection following ventricular mapping. Occasionally, transplantation is used to treat intractable ventricular arrhythmias.

4.

Find out how long it is since the transplant was performed. Ask whether there were any problems with the surgery – either technical or involving acute rejection. Find out how long the patient was in hospital and what further admissions to hospital have occurred since the operation. Ask whether a permanent pacemaker was inserted. Some patients awaiting transplant may have been given a ventricular assist device as a bridge to transplant: ask whether that was necessary.

5.

Endomyocardial biopsies are fairly memorable events and the patient should be able to tell you how often these have been performed and when the last one was obtained. It is now routine to perform them at weekly intervals for the first 3 weeks after operation, every 2 weeks for the following month and every 6 months after that for patients whose condition is stable.

6.

Find out what drugs the patient is taking currently. Transplant patients should not require antifailure treatment, but will, of course, be taking immunosuppressive drugs. Almost all patients are now maintained on cyclosporin; the dose is determined by its serum level. Cyclosporin and tacrolimus are nephrotoxic and cause hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. Newer immunosuppressive drugs include mycophenolate and rapamycin. Diltiazem is often used as a cyclosporin-sparing agent. It dramatically reduces cyclosporin metabolism and therefore the cost of treating patients. Often azathioprine is also prescribed and the dose is adjusted according to the white cell count.

7.

Patients are often well informed about symptoms suggesting rejection – often these resemble an attack of pericarditis. The patient may know of boosts of prednisone that have been given for rejection episodes. Early episodes of rejection are often treated with 1 g of methylprednisolone IV for 3 days. Later rejection tends to be milder and may respond to an increase in oral steroids. Severe rejection is often treated with antithymocyte globulin or the murine monoclonal muromonab-CD3. Repetitive rejection may be treated with total lymphoid irradiation or methotrexate.

8.

Enquire about complications of immunosuppression (

Table 5.8

). Many patients are also taking regular antibiotics to prevent

Pneumocystis jirovecii

(formerly

carinii

) infection. Cotrimoxazole twice daily 3 days a week is a common regimen.

Table 5.8

Commonly used immunosuppressants for heart transplant patients

| DRUG | SIDE-EFFECTS | MONITORING/AVOIDANCE |

| Steroids | Cushingoid, diabetes, osteoporosis | Minimal dose |

| Cyclosporin | Renal impairment, hypertension, neurotoxicity | Blood levels, drug interactions |

| Mycophenolate | Mild marrow suppression, gastrointestinal upset | Reduce dose, check FBC |

| Methotrexate | Hepato- and marrow toxicity | FBC, liver function tests |

| Azathioprine | Hepato- and marrow toxicity, pancreatitis | FBC, liver function tests, TPMT |

FBC = full blood count. TPMT = thiopurine methyltransferase

9.

Some general questions about the transplant patient’s current life are very relevant. Find out how much difference has occurred in the patient’s exercise tolerance and whether he or she has been able to go back to work. If the patient is currently an inpatient, find out why he or she has been admitted to hospital on this occasion. Ask about the patient’s family and how they have coped with the illness and the transplant itself. Make some discreet enquiries about the patient’s finances and whether there have been any problems returning to the transplant hospital for the various investigations required.

10.

Ask about routine cardiac catheterisation. This is typically performed biannually in patients who have had transplants. Coronary artery intimal proliferation can cause ischaemic heart disease in the transplanted heart. Because the heart has been denervated there is not usually any pain. However, there are now patients in whom re-innervation seems to have occurred and led to symptoms of angina. This allograft

arteriopathy is one of the most important problems after transplant. It represents a rejection phenomenon. The condition is usually diffuse, but once lesions causing 40% coronary stenosis have occurred, the prognosis is quite poor: the 2-year survival rate is only about 50%. The condition is present in 10% of recipients at 1-year post-transplant and in 50% at 5 years. Once myocardial infarction has occurred, the 2-year survival rate is only 10–20%. Although the disease is a form of rejection, it is still considered important that the patient’s cholesterol level be kept as low as possible. Find out whether the patient knows what his or her cholesterol level is and what treatment is being used to keep it low. Intravascular ultrasound is used increasingly to detect subclinical vasculopathy and to study the benefits of various antirejection regimens.

11.

Hypertension is another important post-transplant problem. It is associated with the use of cyclosporin. Ask about blood pressure control and treatment.

12.

Transplant patients have an increased risk of malignancy. Skin cancers (basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas) are common. There is also a higher incidence of lymphoproliferative disorders. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) is an increasingly recognised complication of the immunosuppression required for organ transplants. The incidence in heart transplant patients is less than that for those with liver transplants, but more than that for those with renal transplants. Primary or reactivated Ebstein-Barr virus infection is thought to be the cause. The lesions tend to occur in unusual extranodal sites. Reduction in the amount of immunosuppression will sometimes help, but antiviral treatment with acyclovir or interferon may be necessary.

The examination

1.

If the transplant has been successful, there should not be many signs. A median sternotomy scar will be present.

2.

Look for signs of cardiac failure and pericarditis. Pericarditis can be an indication of rejection.

3.

Note the small scars in the neck at the point of introduction of the endomyocardial biopsy forceps.

4.

Look for any evidence of Cushing’s syndrome from steroid therapy.

5.

Examine the chest carefully for signs of infection, examine the mouth for candidiasis, look for infection at intravenous access sites and look at the temperature chart.

Investigations