Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (24 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Pursed lip breathing and postural changes may be of value. Maintain adequate hydration.

5.

Steroid use may be effective in an acute exacerbation and as a way of excluding asthma if there is persisting doubt. A trial of high doses for 2 weeks may be beneficial when bronchodilators are insufficient. Maintenance steroid treatment should be given only if a short course has been shown objectively to be effective (i.e. improved respiratory function test results). Use the lowest dose possible. The associated weight gain, loss of muscle strength and osteoporosis may make things worse.

6.

Annual influenza vaccine and 5-yearly pneumococcal vaccine are useful. Always know the immunisation status!

7.

Pulmonary rehabilitation programs have been demonstrated in randomised controlled trials to improve symptoms and quality of life, but not to prolong life. Exercise and weight reduction increase patients’ wellbeing, but not their lung function.

8.

Domiciliary oxygen is indicated for patients with a

Pa

O

2

of <55 mmHg or cor pulmonale and a

Pa

O

2

of <59 mmHg. There is evidence that mortality rates are decreased by the use of domiciliary low-flow oxygen given for 19 hours per day (especially during sleep). This may work by reducing the progression of pulmonary hypertension. Find out what type of oxygen supplementation the patient uses (e.g. concentrator, cylinders) and how this is managed with regard to convenience and cost.

9.

Consider treatment of cor pulmonale. Heart failure is likely to improve with successful treatment of the lung disease. Spironolactone and diuretics may be useful.

10.

Alpha

1

-antitrypsin deficiency can be treated by replenishing the missing antiprotease, which re-establishes antineutrophil elastase protection for the lower lung zones. An IV preparation can be administered weekly or monthly. This expensive treatment is indicated only if alpha

1

-antitrypsin levels are below 11 μmol/L. Only a small proportion of people with alpha

1

-antitrypsin deficiency develop COPD and the treatment is not recommended unless there is demonstrated disease.

11.

Lung transplantation is an option for younger (<65 years) patients with end-stage disease and without serious co-morbidity who have not had previous thoracic surgery. The 1-year survival rate is more than 80% for this group.

12.

Lung reduction surgery is an option for some severely symptomatic patients who have stopped smoking. Those with predominately upper lobe emphysema were thought more likely to benefit. Thorascopic removal of the worst lung segments did seem to give symptomatic improvement to many patients. However, the procedure has lost favour and is now rarely performed. This is partly because lung function continues to decline. Symptomatic benefit may be lost within a year and accelerated decline in lung function may occur. Pulmonary hypertension is a contraindication and air leaks from the stapled lung are the most important postoperative problem. This operation was combined with an intensive rehabilitation and exercise program, which may in itself account for some of the postoperative improvement.

13.

The use of positive pressure ventilation (CPAP) is a possible option for long-term management.

14.

The management of severe exacerbations is difficult, particularly when these are associated with severe carbon dioxide retention and a reduced level of consciousness. Steroids and theophylline are both used commonly for these patients. Evidence for their effectiveness is not strong. Non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP) via a mask may improve symptoms and avoid the need for intubation. Intensive care units usually require some evidence of a potentially reversible problem before allowing intubation and mechanical ventilation. The patient’s own wishes are important and should be obtained before he or she is too sick to make a decision.

Sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea is an increasingly recognised clinical syndrome that should be suspected in patients who have obesity, hypertension, fatigue, excessive snoring or unexplained respiratory failure. Obstructive sleep apnoea is a common cause of sleep disturbance, but by no means the only explanation for it. Sleep apnoea patients commonly have some combination of these symptoms.

The history

1.

Classically, in obstructive sleep apnoea, anyone else in the house will describe a history of loud snoring at night, associated with multiple periods of cessation of respiratory movement and waking and gasping for breath. Apnoeas of more than 10 seconds are considered significant, but for patients with this condition pauses of up to 2 or 3 minutes can occur and pauses of 30 seconds are common. Remember, though, that the majority of people who snore (40% of middle-aged men and 20% of middle-aged women) do not have sleep apnoea and brief apnoeas not associated with signs of arousal are normal for many people.

2.

Ask the patient whether there have been problems with excessive daytime sleepiness and with working during the day.

3.

Enquire whether the patient drinks alcohol and, if so, how much. Alcohol consumption is a common exacerbating factor.

4.

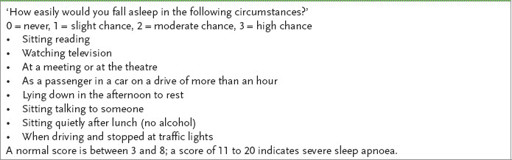

Calculate the patient’s Epworth sleepiness score (

Table 6.7

).

Table 6.7

The Epworth sleepiness scale

5.

Ask whether there is a history of hypertension and whether this has been treated (50% of these patients have hypertension). Find out whether the patient has had angina or arrhythmias at night; both of these may be precipitated by the hypoxia associated with apnoea. Heartburn and non-cardiac chest pain caused by gastro-oesophageal reflux are also common.

6.

Enquire about medications, such as hypnotics, that may have been prescribed for poor sleeping, but actually aggravate sleep apnoea.

7.

Ask about a previous diagnosis of COPD or symptoms of heart failure. The recurrent increase in afterload that occurs during apnoeic episodes can precipitate or exacerbate left ventricular failure. Fewer than 10% of patients develop right heart failure and significant pulmonary hypertension.

8.

Ask about a history of tonsillar enlargement or throat surgery. In a few sleep apnoea patients there is a clear anatomical cause for the obstruction.

9.

In the absence of excessive snoring, central sleep apnoea needs to be considered for a patient with the other symptoms.

10.

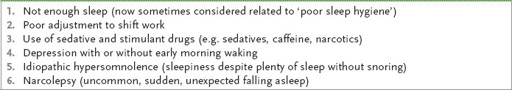

Ask about symptoms suggestive of narcolepsy rather than sleep apnoea (

Table 6.8

). The sudden sleep attacks of narcolepsy can occur at any time, including during meals, conversation or driving. Patients may also report sudden loss of muscle tone from emotion (e.g. laughter). The result is an unexpected dropping of an object or a sudden buckling at the knees and falling down; cataplexy should be considered. Cataplexy is usually associated with narcolepsy, although it may precede narcolepsy by several years.

Table 6.8

Differential diagnosis of daytime sleepiness

11.

Ask about symptoms of the restless legs syndrome (RLS), which may also lead to daytime sleepiness (remember, RLS is associated with iron deficiency).

12.

The use of diuretics or insulin may predispose patients to inadequate sleep and should not be confused with sleep apnoea.

13.

Ask whether the patient drives a motor car and whether the risks of driving have been discussed. Also ask whether it has been recommended that the anaesthetist be informed of the patient’s sleep apnoea before the administration of an anaesthetic.

14.

Find out whether a CPAP mask has been prescribed and whether the patient finds it comfortable enough to use. Up to 50% of patients are unable to tolerate the device. If the treatment is tolerated, find out whether it has made a difference – many patients report a dramatic reduction in daytime sleepiness and improvement in wellbeing.

15.

Find out how this chronic condition has affected the patient’s family and work.

The examination

1.

Assess the BMI, but remember that up to 50% of patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and most patients with central sleep apnoea are not obese.

2.

Respiratory examination is usually normal.

3.

Measure the blood pressure and look in the fundi for signs of hypertension.

4.

The cardiovascular system should be examined carefully for evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

5.

Inspect the head, neck and mouth for signs of uvular enlargement and macroglossia or tonsillar hypertrophy – ‘pharyngeal crowding’. Look at and measure the neck circumference.

6.

Perform a neurological examination to look for signs of autonomic neuropathy (e.g. diabetes mellitus, Shy-Drager syndrome), brain stem lesions or spinal cord disease (e.g. tumour, demyelination), which can cause central sleep apnoea.

7.

Examine for neurological causes of obstructive sleep apnoea, such as myasthenia gravis or muscular dystrophy.

8.

Look for signs of hypothyroidism or acromegaly.

Investigations

1.

Consider sleep study monitoring (polysomnography) with the electroencephalogram, chin electromyogram, electro-ocular monitoring (to detect rapid eye movement (REM) sleep), oximetry,

Pa

CO

2

monitoring and, if indicated, ECG monitoring (for arrhythmias).

2.

For a definitive diagnosis, the apnoeic spells must be 10 seconds or longer in duration and at least five per hour must be recorded over several hours. The apnoea hypopnoea index (AHI) is the total number of episodes of apnoea or hypopnoea per night divided by the number of hours of sleep (mild 5–15; moderate 6–30; severe >30). A value of 5 or greater is considered abnormal, but is probably not diagnostic in the absence of symptoms.

3.

For patients with typical features of the condition, home

Pa

O

2

monitoring overnight may be an option. A positive test (several significant desaturation episodes per hour) is enough evidence to justify treatment. A negative test, however, does not exclude the diagnosis.

4.

Narcolepsy can also be diagnosed by a sleep study.

5.

Hypothyroidism should be excluded with thyroid function tests if there is any clinical suspicion.

6.

Check for proteinuria (uncommon, but may reach nephrotic levels in severe obesity).

7.

Look at ECG for arrhythmias. Echocardiography may be indicated to enable estimation of pulmonary artery pressures and to assess right ventricular function.

Treatment

1.

If the patient has hypothyroidism, thyroid hormone replacement may reverse sleep apnoea.

2.

Concomitant diseases such as cardiac failure, hypertension and asthma need to be treated vigorously. Nasal decongestants may be helpful. Weight loss is of value, but may be difficult to achieve. Respiratory depressants, such as tranquillisers, should be withdrawn.

3.

CPAP is of value for long-term treatment of irreversible obstructive sleep apnoea (

Table 6.9

). CPAP devices are not always well tolerated, but the devices are improving steadily in comfort and portability. Nasal CPAP is effective in the majority of patients who can adjust to it. If there is residual sleepiness despite regular use of CPAP, modafinil may be a useful adjunct.

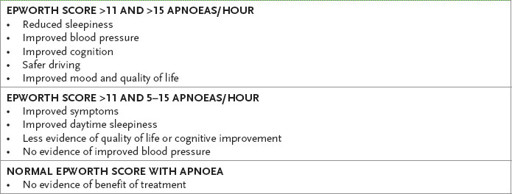

Table 6.9

The effects of treatment for sleep apnoea from randomised clinical trials