Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (28 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

The chest X-ray is usually abnormal (

Table 6.16

) and the changes can be classified into three stages:

Table 6.16

Chest X-ray changes in sarcoidosis

•

Stage 1

Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy alone

•

Stage 2

Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and pulmonary infiltration

•

Stage 3

Pulmonary infiltration without hilar lymphadenopathy

Patients with stage 1 X-rays are considered to have an acute reversible form of the disease, whereas the other stages tend to be more chronic. The chest X-ray may show paratracheal lymphadenopathy; cavitation and pleural effusions are rare. Cavities may become colonised with

Aspergillus

. CT scans of the chest may show a ground-glass appearance when active alveolitis is present. Always think about excluding tuberculosis and histoplasmosis.

5.

If there is parenchymal granulomatous involvement, respiratory function tests reveal the changes that are typical of interstitial lung disease, with reduced lung volumes and diffusing capacity, but a normal FEV1/FVC ratio. Occasionally, a mixed pattern of obstruction and restriction is seen.

6.

Blood gas estimations may show mild hypoxaemia.

7.

A gallium-67 lung scan usually shows a pattern of diffuse uptake, but increased uptake in the lacrimal and parotid glands (panda sign) or in the right paratracheal and left hilar areas (lambda sign) is more specific for sarcoidosis. Enlarged nodes also tend to show up on the scans.

8.

Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy will usually establish the pathological diagnosis. Bronchioalveolar lavage will show an increase in the number of CD4

+

T-helper lymphocytes. However, this is not diagnostic of the condition.

9.

Biopsy of lymph nodes, skin or liver may be diagnostic. The non-caseating granulomas found in sarcoidosis are non-specific; they are also found in berylliosis, leprosy, hypersensitivity pneumonitis and granulomatous infection, and in lymph nodes that drain adjacent carcinomas.

Treatment

Indications for treatment are lack of resolution of active pulmonary sarcoidosis with increasing symptoms or worsening lung function; neurological, renal or cardiac

complications; major eye disease; and occasionally severe systemic symptoms (e.g. fever and weight loss).

1.

The drug of choice is prednisolone. This is begun in high dose (1 mg/kg) for up to 6 weeks and then tapered over the following few months. Treatment is continued for 12 months. The prognosis is good. About 50% of patients develop some permanent organ damage but, in most, this is mild.

2.

Patients who require longer treatment may be offered steroid-sparing drugs, including chlorambucil, methotrexate or azathioprine.

3.

Hydroxychloroquine may be useful for skin disease.

4.

Infliximab (a monoclonal antibody directed at tumour necrosis factor (TNF)) has been shown to improve lung function for patients already being treated with steroids and cytotoxics.

Cystic fibrosis

The survival of children with cystic fibrosis into adult life is now common. More than 50% of patients reach the age of 30 years and the prognosis is improving all the time. Although paediatricians are often reluctant to give up these patients, they are increasingly coming under the care of adult physicians. A small number of cases are diagnosed in adult life. They, unfortunately, tend to spend long periods in hospital and are thus readily available for clinical examinations.

Cystic fibrosis is a common, serious, congenital inherited defect in Caucasian people. It has an autosomal recessive inheritance and the gene has been identified. The mutation is in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein gene on chromosome 7. The trait is present in about 1 in 25 Caucasians and 1 in 3000 has the condition. It is rare in other races. It is a chronic disease that can affect the lungs, pancreas, bowel, liver and sweat glands.

The history

1.

Ask about presentation:

a.

age at diagnosis – milder forms are sometimes not diagnosed until adult life

b.

presenting symptoms – the patient may have been told that he or she had meconium ileus as a baby or recurrent respiratory infections in early life; failure to thrive may suggest the diagnosis

c.

pulmonary symptoms – cough and sputum, haemoptysis, wheeze, dyspnoea

d.

nasal polyps and sinusitis – relatively common

e.

gastrointestinal symptoms – problems maintaining weight; diarrhoea and steatorrhoea (pancreatic malabsorption); constipation and abdominal distension and bowel obstruction (defective water excretion into the bowel)

f.

heat exhaustion in hot weather – patients with cystic fibrosis can lose large amounts of salt in their sweat, which sometimes causes problems, particularly in the tropics

g.

cardiac symptoms – the patient may know of cardiac involvement (cor pulmonale is a late development)

h.

jaundice and variceal bleeding – focal biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension occur occasionally

i.

diabetes mellitus – occurs in 10% of patients with cystic fibrosis.

2.

Ask about diagnosis. The patient may know whether a sweat test was performed. Collection of sweat and measurement of the chloride concentration is still the accepted method of diagnosing the condition. A sweat chloride concentration of more than 70 mmol/L suggests cystic fibrosis in an adult. Otherwise, a combination of respiratory

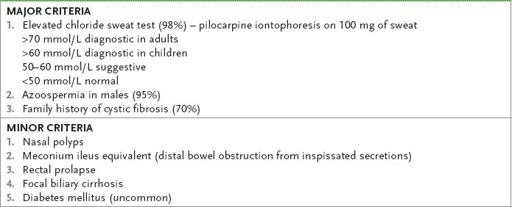

and malabsorptive problems may be considered enough to make the diagnosis. A list of the major and minor diagnostic criteria is presented in

Table 6.17

. DNA markers are likely to be used increasingly in the diagnosis. At the moment this is difficult because there are a large number (over 1300) of abnormal genotypes that can result in the disease. Screening for the most common mutations is especially helpful for those patients who have the clinical syndrome but a negative sweat test (1–2%).

Table 6.17

Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis

3.

Ask about family history – the autosomal recessive inheritance means siblings and other close relatives may be affected.

4.

Ask about treatment. Pulmonary disease is the main determinant of mortality. Aggressive treatment of the pulmonary complications has had the greatest effect on the improvement in life expectancy. The patients are usually well aware of this and are largely responsible for their own treatment. The condition is a chronic suppurative progressive one causing bronchiolitis, bronchitis, pneumonia and eventually bronchiectasis. The pathology is probably the result of the formation of viscous mucous plugs, which lead to distal infection and lung damage.

a.

The mainstay of treatment is physiotherapy, which the patient, with help from family and a physiotherapist, performs. Ask about deep breathing, percussion, postural drainage, the use of a flutter valve and the forced expiratory technique called ‘huffing’.

b.

Mucolytic drugs are of doubtful benefit and may even be harmful.

c.

The patient should also know what antibiotics have been used and whether continuously or intermittently. Nebulised bronchodilators and antibiotics are commonly prescribed.

Staphylococcus aureus

and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

are common pathogens because of their ability to grow on the abnormal bronchial mucus of cystic fibrotic lungs. The patient may know if the pseudomonas is antibiotic resistant.

d.

Ask whether treatment for complications, such as haemoptysis, cor pulmonale or pneumothorax, has been required. Minor haemoptysis, where less than 250 mL of blood is lost, occurs in about 60% of patients. Major haemoptysis occurs in about 7% of patients and bronchial artery embolisation may be required. Cor pulmonale may require treatment with diuretics, spironolactone and possibly vasodilators, but aggressive treatment of the lung disease and supplementary oxygen are more important in the long term. Pleurodesis used to be the treatment of choice for recurrent pneumothorax, but this may result in a contraindication to lung transplantation. Macrolide antibiotics, especially azithromycin, are being used because of their anti-inflammatory properties.

5.

Enquire about gastrointestinal symptoms. These tend to be less of a problem, but malabsorption may make weight gain very difficult for these patients. Ask what pancreatic enzyme replacement the patient uses and how often.

6.

Ask about the number of admissions to hospital over the past 12 months and the length of each stay. Routine admission to hospital three or four times a year for intensive physiotherapy and nebulised antibiotics and bronchodilators is not advantageous.

7.

Enquire about social support. Ask whether the patient knows about or belongs to the local cystic fibrosis association and whether he or she has been in touch with other affected patients. Try to find out tactfully whether the patient understands the inheritance of the disease; male patients may know that azoospermia is usually present due to destruction of the vas deferens by abnormal secretions (95%). Eighty per cent of women are fertile, and pregnancy and breastfeeding are often successful. Find out in some detail how a young adult copes with this debilitating and life-shortening disease.

The examination

1.

Look at the patient’s size and physique. Muscle bulk is considered a good indicator of the severity and prognosis in a particular patient. Measure the patient’s height and weight.

2.

Ask the patient to cough. Listen for a loose cough and examine any sputum for the degree of purulence.

3.

Now examine the respiratory system carefully. Note clubbing, which is present in the majority of patients. Look for abnormal chest wall development. Estimate forced expiratory time and examine the chest, listening particularly for crackles, wheezes and reduced breath sounds.

4.

Examine the heart for signs of cor pulmonale and right ventricular failure.

5.

Examine the abdomen for signs of faecal loading, especially in the right iliac fossa.

Investigations

1.

Sputum culture is most important. Colonisation with

H. influenzae

and

S. aureus

tends to occur in young patients and this is often followed by nosocomial

E. coli

and

Proteus

spp. By the age of 10 years,

Pseudomonas

is the main pathogen in most patients, but usually it does not cause systemic infection.

2.

A full blood count should be asked for to look for anaemia, which may be caused by malabsorption or chronic disease; the white cell count may indicate acute infection. Polycythaemia is rare, despite chronic hypoxia.

3.

The electrolyte levels and liver function tests should be looked at. There may be evidence of deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K). The creatinine level should be known before aminoglycosides are used.

4.

The chest X-ray (see

Fig 6.12a and b

) should be looked at carefully and should be compared with previous films if these are available. Increased lung markings are present in 98% of patients. These occur particularly in the upper lobes. Cystic bronchiectatic changes occur in more than 60% of patients. Mucous plugs may be seen in one-third and atelectasis occurs in just over 10% of patients. Look also for pneumothorax and pleural changes at the site of previous pneumothoraces or pleurodesis.