Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (21 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

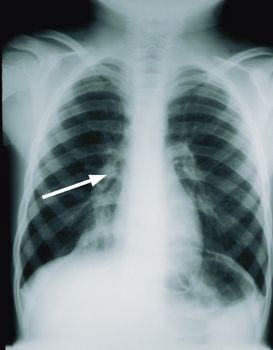

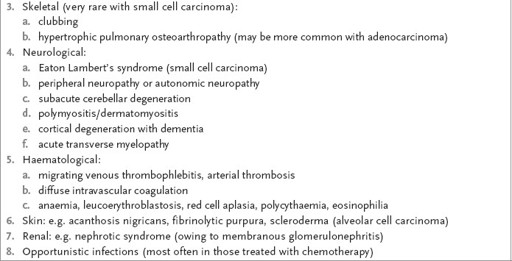

Table 6.2

Causes of bronchiectasis

Notes:

Lung carcinoma rarely causes bronchiectasis as death tends to intervene first.

Aboriginal Australians who grew up in remote areas are at particular risk.

7.

Ask how the disease interferes with the patient’s life (e.g. work). Infertility is usual in men with primary ciliary dyskinesia and is variable in affected women.

The examination

Examine the respiratory system carefully (see

Table 16.10, p. 342

).

1.

Particularly note the unpleasant purulent sputum.

2.

Examine carefully for clubbing, the yellow nail syndrome and localised crackles and wheezes.

3.

Look for the position of the apex beat (don’t miss dextrocardia – Kartagener’s syndrome) and for the signs of right heart failure.

4.

Consider the complications and look for them. These include:

a.

pneumonia

b.

pleurisy

c.

empyema

d.

lung abscess

e.

cor pulmonale

f.

cerebral abscess (very rare)

g.

amyloid (rare, but an important topic in the examination).

Investigations

Investigations should include:

•

chest X-ray film

(see

Fig 6.1a

), which may be normal, or it may show 1–2 cm cystic lesions or, more often, streaky infiltration and thickened bronchial walls (tram tracking), especially in the lower lobes

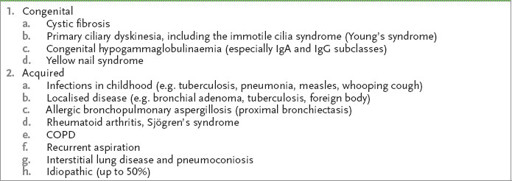

FIGURE 6.1

(a) Right middle lobe bronchiectasis. Note the increased lung markings and the thickened bronchial walls (arrow).

(b) CT scan of the chest of a patient with bronchiectasis. Note the thickened bronchial walls (arrow). Figures reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

•

sputum microscopy and culture

; the common organisms are

Haemophilus influenzae

,

Pseudomonas

,

Escherichia coli

, pneumococcus, mycobacteria and

Staphylococcus aureus

•

immunoglobulin (IgG, IgM, IgA) levels

(hypogammaglobulinaemia)

•

tests for cystic fibrosis and immotile cilia syndrome in young adults

•

blood film for eosinophilia

, which may indicate allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or asthma

•

ventilatory function tests

, which may show a restrictive defect or an obstructive pattern. It is therefore more useful in assessing severity than in making the diagnosis. A patient with bronchiectasis with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV

1

) of <40% predicted is said to have severe disease

•

arterial blood gas estimations

, which may show mild or moderate hypoxia and, later, respiratory failure – defined as an arterial oxygen tension (

Pa

O

2

) <60 mmHg or an arterial carbon dioxide tension (

Pa

CO

2

) >50 mmHg

•

high-resolution CT scanning of the chest

(see

Fig 6.1b

), which has replaced bronchography and is indicated in most patients to confirm the diagnosis. The typical findings are of airway dilatation (usually defined as a diameter greater than that of the accompanying branch of the pulmonary artery). Temporary dilatation can occur during acute infections so the scan should be performed when the patient is stable. Remember the radiation dose of an HRCT is about 8mSv and the test should be used sparingly, especially in children and young adults.

The extent of the disease is usually generalised. If the bronchiectasis is localised, resection may be indicated as long as the underlying cause is not systemic.

Treatment

The principles of treatment are as follows.

1.

The facilitation (or maximisation) of clearance of sputum and the treatment of infection with antibiotics and of bronchoconstriction with bronchodilators.

2.

Inhaled steroids may be of value if there is bronchial reactivity.

3.

Twice-daily postural drainage (20 minutes morning and night) or newer physiotherapy techniques should be recommended (e.g. use of a flutter valve). Head-down drainage is now discouraged because of the risk of aspiration.

4.

The use of antibiotics during exacerbations is routine, though of unproven benefit, and prednisone in tapered doses may be useful. The use of prophylactic nebulised antibiotics is a controversial treatment. Problem pathogens include

Mycobacterium avium

complex (MAC),

Pseudomonas

and

Aspergillus

. Patients with frequent infections may benefit from long-term antibiotic treatment with macrolides. Recombinant deoxyribonuclease is useful for cystic fibrosis patients but may be harmful for other patients with bronchiectasis.

5.

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are advisable for all patients.

6.

Treatment of heart failure should go

pari passu

with that of the lung disease.

7.

Immunoglobulin deficiency can be treated with monthly IV injections of immunoglobulin, which decrease the incidence of infection and the need for hospitalisation.

8.

Massive haemoptysis may occur as a result of bronchial wall erosion and the increased vascularity of the bronchial walls. It may respond to bronchial artery embolisation.

9.

Smoking (including of marijuana) cessation is always essential.

10.

Home oxygen is of unproven benefit but often prescribed (to non-smoking patients) with severe disease (FEV

1

<40%). A screening test for eligibility is an oxygen saturation of 93% or less on room air.

11.

Surgery should be considered for localised disease to prevent progression or as treatment of intractable haemorrhage.

12.

Transplant is occasionally appropriate for end-stage disease.

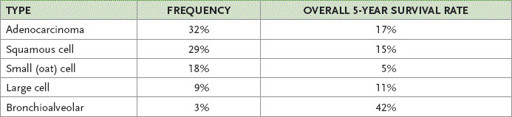

Lung carcinoma

Lung carcinoma is a common disease that candidates often encounter in the examination. It can pose a diagnostic and management problem, and remains a leading cause of cancer death in men and women. At diagnosis only 20% of patients will have local disease and half will have disseminated disease. The overall 5-year survival rate is less than 15%. The major cell types are set out in

Table 6.3

. Over the last 20 years, adenocarcinoma has become more common than squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 6.3

Carcinoma of the lung – cell types

The history

1.

Find out how the diagnosis was made or suspected – a proportion of patients are asymptomatic and were diagnosed after a routine chest X-ray or scan.

2.

Ask about the duration of illness and respiratory symptoms (e.g. haemoptysis, dyspnoea, increasing cough, chest pain).

3.

Enquire about a history of unresolved pneumonia, pleural eff usion or lung abscess.

4.

Ask about systemic symptoms (e.g. weight loss, loss of appetite, lethargy).

5.

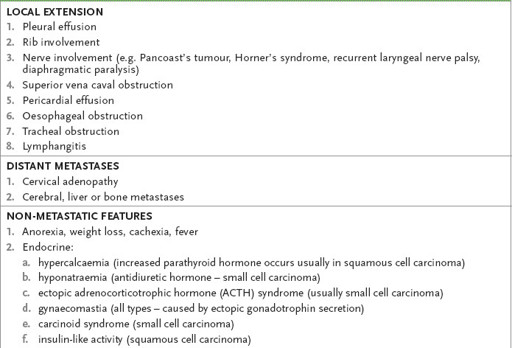

Determine metastatic and non-metastatic symptoms (

Table 6.4

).

Table 6.4

Metastatic and non-metastatic manifestations of lung carcinoma

6.

Ask about aetiology:

a.

smoking and exposure to the cigarette smoke of others (a dose-response relationship – long-term smokers have a 10- to 30-fold risk; discontinuation of smoking reduces the risk over 10–15 years, but the relative risk does not return to 1.0); women have a higher risk for a given level of exposure to cigarette smoke than men (1.5:1); there is a familial association for first-degree relatives

b.

occupational history (e.g. asbestos exposure, uranium miners); remember, the effect of asbestos plus smoking is synergistic, not additive

c.

chronic scarring (e.g. tuberculosis, scleroderma, interstitial lung disease (ILD) may be associated with adenocarcinoma).