Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (30 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Biopsies of the pleura, lymph nodes or bone marrow may be needed. Bronchoscopy is sometimes necessary to exclude other causes of X-ray changes.

5.

The fasting blood sugar level should be taken to rule out diabetes mellitus.

6.

HIV patients may have TB despite a completely normal chest X-ray. They may also have less typical chest X-ray findings – often lower lobe changes without cavities. They are more likely to have infection with other mycobacteria, such as MAC. Remember that the diagnosis can be made even when the organism is not isolated. All patients with TB should be tested for HIV infection.

Treatment

There are four first-line drugs for the treatment of TB: isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. These are all given orally. Second-line drugs tend to be more toxic and are used only for organisms resistant to the first-line drugs. They include streptomycin, quinolone, kanamycin and amikacin (parenteral), and cycloserine, ethionamide and PAS (para-aminosalicylic acid). The initial isolate should undergo drug susceptibility testing, especially if treatment seems to have failed or there is a relapse of symptoms.

Treatment of latent TB reduces the risk of transmission and the risk of progression to active disease by up to 90%. Nine months of treatment with isoniazid is commonly recommended.

1.

Treatment begins with a combination regimen of three drugs (usually isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide) for 2 months. A fourth drug (usually ethambutol) is often given until the organism’s sensitivities are available. The aim here is to kill the majority of the organisms, improve the patient’s symptoms and render him or her non-infectious. This is followed by 4 months of treatment with two drugs (isoniazid and rifampicin).

2.

Adherence to the full course of treatment is very important, but difficult to ensure. Complicated public health arrangements, with monitoring of compliance, may be needed to enforce treatment. Direct observed treatment (DOT) is insisted on by public health authorities if compliance seems doubtful. These patients present as required to be observed taking their treatment.

3.

The response to treatment is monitored by repeat sputum cultures until they become negative. Persisting positive cultures after 3 months suggest resistance of the organism or non-adherence on the part of the patient. Patients are probably not an infectious risk if no sputum is produced or if the sputum is consistently acid-fast bacilli (AFB) negative.

4.

Patients need to be aware of the most important side-effects of treatment, which include hepatitis (up to 5% in the general population and 30% in HIV patients), deafness and visual disturbance (

Table 6.18

). Small increases in the transaminases (to three times normal) are no cause for alarm and are poor predictors of significant hepatotoxicity. Treatment should be reviewed immediately if jaundice develops.

5.

Multiple drug resistance is increasingly common and should be expected if the infection was acquired from a patient with a known resistant organism or if the infection was acquired in parts of Asia or South America. The addition of a fluoroquinolone to the regimen should be considered while resistance studies are underway.

6.

Prevention of infection by vaccination with BCG is not widely practised in Australia; its effectiveness is uncertain. In high-risk areas vaccination of children has been shown to reduce the risk of cerebral TB. The Mantoux test should be interpreted as usual regardless of previous BCG vaccination (15 mm is a positive skin test for low-risk individuals). If the Mantoux test is positive (≥5 mm) in a high-risk group (patients with exposure to TB (especially household contacts), or who are HIV infected, on prolonged steroid treatment (≥15 mg ≥1 month) or have undergone organ transplant), prescribe treatment with isoniazid for latent TB (5 mg/kg/day for 9 months). If close (e.g. household) contacts are negative on the tuberculin test, treat for 12 weeks and repeat the skin test: this reduces the chance of the development of open TB by 90%. If the test is ≥10 mm in an intermediate-risk group (IV drug abusers, prisoners, healthcare workers, nursing-home patients, homeless people or those with diabetes), also treat with isoniazid. Screening of contacts and high-risk patients with tuberculin testing is an important public health measure.

Lung transplantation

Although lung transplantion is an uncommon procedure, transplant patients have chronic management problems that make them very suitable long cases. The examiners will have the opportunity to ask questions about the patient’s underlying pulmonary problem, the general indications for lung transplant, management of the complications of transplant and, of course, the types of social problems associated with a severe chronic illness. Occasionally, patients who are being assessed for possible transplant may be suitable for the clinical examinations.

The history

1.

Find out why the patient is in hospital (it may just be for the clinical examinations).

2.

Obtain some basic information about the transplant: how long ago, how many lungs were transplanted and whether the patient’s heart was also originally someone else’s.

3.

Enquire what the original lung disease was. Emphysema (including that caused by alpha

1

-antitrypsin deficiency) is the most common indication, accounting for about half the unilateral transplants and one-third of the bilateral transplants. Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension, cystic fibrosis and Eisenmenger’s syndrome are the main indications for heart/lung transplants.

4.

Ask how successful the procedure has been from the patient’s point of view. Lung function tests should be normal after bilateral transplant and nearly so after unilateral transplant. A decline in lung function test measurements of more than 10% usually is important.

5.

Find out what complications the patient can remember. Ask about known rejection episodes and how they were managed. Have there been difficult infections? The patient may know what organisms have been detected. Stenosis of a bronchial anastomosis site is an occasional early problem. This is often treated with dilatation and stenting.

6.

Review what medications the patient is taking. If necessary, prompt for prednisolone, cyclosporin, mycophenolate, azathioprine and tacrolimus. Find out whether blood levels of tacrolimus and cyclosporin are measured regularly. Remember that these two drugs are metabolised via the cytochrome P450 pathway in the liver and blood levels may be affected by other medications (so make sure you review all of the drugs being taken).

7.

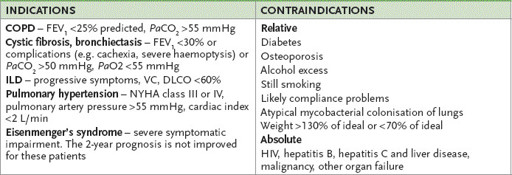

If the patient is being assessed for transplant, try to find out whether the patient fits the current guidelines for transplant (

Tables 6.19

and

6.20

). In general, suitable patients are sick enough to require the operation but not too sick to present an intolerable operative risk.

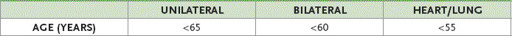

Table 6.19

Age criteria for lung transplant

Table 6.20

Indications and contraindications for lung transplant

DLCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; VC = vital capacity; ILD = interstitial lung disease.

8.

Establish how the patient has coped with the procedure, its complications and the immunosuppressants. What regular follow-up is carried out? Many transplant units have a transplant nurse available after hours whom the patient can contact directly if there are problems.

The examination

Perform a thorough respiratory examination.

1.

Look especially for thoracotomy scars and attempt an assessment of the patient’s functional capacity (e.g. look for signs of breathlessness while the patient is undressing and, if the room is big enough, get the patient to walk backwards and forwards).

2.

Listen for end-inspiratory pops and squeaks (bronchiolitis obliterans at an advanced stage can be associated with the development of bronchiectasis).

3.

Note signs of infection – fever and areas of bronchial breathing or crackles.

4.

Look for sputum and assess the cough.

5.

Is the patient Cushingoid?

Management

The detection of complications and their management is likely to dominate the discussion.

1.

Rejection

. Early rejection episodes are common and treated with boost doses of prednisone. Symptoms of acute rejection include malaise, fever, dyspnoea and cough. Clinical assessment may reveal crackles, decreasing FEV1, hypoxia and a raised white cell count. The chest X-ray may show infiltrates and pleural effusions. A transbronchial biopsy tends to be performed if there is any suspicion of rejection and allows an accurate diagnosis. In some places, routine biopsies are performed to detect asymptomatic rejection. It is not clear, however, whether these should be treated.

2.

Infection

. Most lung transplant patients develop infections requiring treatment. Infection is the most common cause of death. A combination of immunosuppression and local problems, such as impaired ciliary activity, are relevant. Infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus, influenza A and paramyxovirus are common and associated with a significant mortality. Invasive fungal organisms, such as

Aspergillus

, result in an even worse prognosis. Patients now receive at least 3 months of routine prophylactic antibiotic, antiviral and antifungal treatment. This approach has improved the early postoperative prognosis.

3.

Immunosuppression

. The usual problems with immunosuppressive drugs occur in lung transplant patients. Renal impairment, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia are frequent problems. Osteoporosis and peripheral neuropathy are also possible problems. Five per cent of lung transplant patients develop post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders.

4.

Bronchiolitis obliterans

. The gradual onset of small airways obstruction is a manifestation of chronic rejection. It does not usually begin until 2 or more years after transplant, but is detectable in at least half of transplant patients within 5 years. It may occur more often in those who have had more frequent acute rejection episodes and in those with a human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch with the donor. There tends to be a very gradual onset of dyspnoea, fatigue and cough. Patients have a slowly decreasing FEV

1

but chest X-rays are often normal. CT scans may show a central mottling opacity. Biopsy will establish the diagnosis. The prognosis is not good. Sometimes an aggressive increase in immunosuppression may stabilise the condition, but it cannot be reversed and often the patient deteriorates rapidly.

5.

Disease recurrence

. Sarcoidosis and some forms of idiopathic ILD can recur in the transplanted lungs.

CHAPTER 7

The gastrointestinal long case

One finger in the throat and one in the rectum makes a good diagnostician.

Sir William Osler (1849–1919)

Peptic ulceration

This long case is usually a straightforward management problem. The most important causes of chronic peptic ulcer disease are

Helicobacter pylori

infection and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including low-dose aspirin. The COX-2-specific NSAIDs have a lower incidence of peptic ulceration. Idiopathic ulcers (

H. pylori

negative, NSAID negative) are increasingly being reported. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma) is a very rare but important cause. Since peptic ulcer disease affects 10% of the population, a history of this condition is not uncommon in the long case. Patients are usually admitted to hospital with peptic ulcer disease because of complications – typically haemorrhage, but more rarely, perforation.