Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (75 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Note:

If the investigations suggest that left ventricular dilatation is present in the presence of a mitral stenosis murmur, consider these other possibilities:

•

associated mitral regurgitation

•

associated aortic valve disease

•

associated hypertension

•

associated ischaemic heart disease.

Echocardiograph (M mode, 2D Doppler and colour flow mapping)

The posterior mitral leaflet maintains its anterior position in diastole and this is pathognomonic. A delayed mitral closure with decreased ejection fraction slope (an M mode index of mitral valve opening) is not pathognomonic but is very suggestive. There may be heavy echoes from thickened or calcified mitral leaflets. On two-dimensional (2D) scanning the valve can be seen doming in diastole. The mitral valve area can be quite accurately determined by 2D echocardiography and Doppler measurements. The valve area is estimated using the pressure half-time measurement. This analysis of Doppler left ventricular inflow is performed routinely when mitral stenosis is suspected. Colour flow mapping makes finding the inflow jet easier and is very sensitive for the detection of any associated mitral regurgitation.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Exertional dyspnoea and falling valve area (when the valve area falls to about 1 cm

2

) with signs of increasing right heart pressures are the usual indications for surgery. It should usually be performed before pulmonary oedema or major haemoptysis has occurred (when the valve area falls to about 1 cm

2

).

HINT

A declaration that the apex beat is ‘tapping’ in quality tells the examiner that you have made the diagnosis of mitral (or very rarely tricuspid) stenosis. It is unwise to allow the word ‘tapping’ to escape your lips unless you are happy that this is the diagnosis.

Mitral regurgitation

CAUSES – CHRONIC

1.

Degenerative disease.

2.

Mitral valve prolapse.

3.

Rheumatic (men more often than women) – rarely is mitral regurgitation the only murmur present.

4.

Papillary muscle dysfunction:

a.

left ventricular failure

b.

ischaemia.

5.

Connective tissue disease – rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis.

6.

Congenital – endocardial cushion defect (including primum atrial septal defect (ASD) and cleft mitral leaflet), parachute valve, corrected transposition.

CAUSES – ACUTE

1.

Infective endocarditis (perforation of anterior leaflet), rupture of a myxomatous cord.

2.

Myocardial infarction (chordae rupture or papillary muscle dysfunction).

3.

Surgery.

4.

Trauma.

CLINICAL SIGNS OF SEVERITY

1.

Enlarged left ventricle.

2.

Pulmonary hypertension (a late sign).

3.

Third heart sound (not always reliable).

4.

Early diastolic rumble.

5.

Soft first heart sound.

6.

Aortic component of second heart sound (A2) is earlier.

7.

Small-volume pulse (very severe).

8.

Left ventricular failure.

RESULTS OF INVESTIGATIONS

1.

ECG:

a.

P

mitrale

b.

atrial fibrillation

c.

left ventricular diastolic overload

d.

right-axis deviation.

2.

Chest X-ray film:

a.

large (sometimes gigantic) left atrium

b.

increased left ventricular size

c.

mitral annular calcification

d.

pulmonary hypertension (much less common).

3.

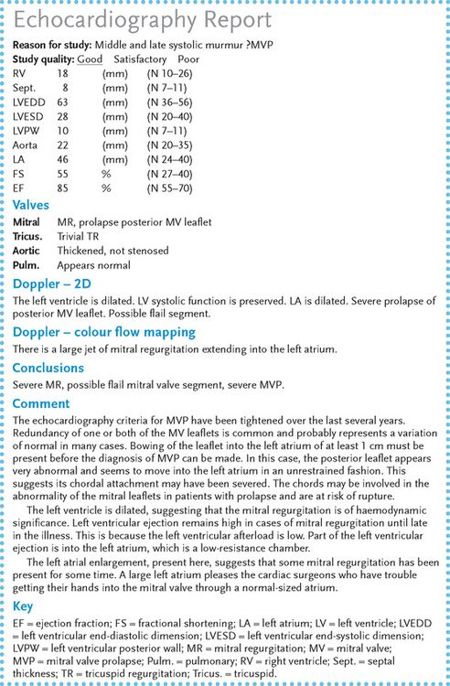

Echocardiography (see

Fig 16.10

) – this will give information about the possible aetiology, the severity and any associated valve or structural abnormalities:

FIGURE 16.10

Echocardiography report in a patient with mitral regurgitation and mitral valve prolapse.

a.

thickened leaflets – rheumatic aetiology

b.

prolapsing leaflet(s)

c.

left atrial size (a sign of chronicity and severity)

d.

left ventricular size and function

e.

Doppler detection of the regurgitant jet in the left atrium; colour mapping of jet size and detection of reversal of flow in the pulmonary veins

f.

other abnormalities (e.g. aortic valve disease as a result of rheumatic carditis or an ASD associated with mitral valve prolapse)

g.

calcification of the mitral annulus – common in elderly people.

Note:

the valve leaflets may not appear abnormal.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

In chronic mitral regurgitation, consider surgery if there are class III or IV symptoms, or if there is left ventricular dysfunction or the left ventricular dimensions have increased progressively. In acute mitral regurgitation, operate if there is haemodynamic collapse (there usually is). Repair of a prolapsing posterior and often anterior leaflet is now undertaken earlier than valve replacement. The short- and long-term results (1% recurrence per year) are so good that the operation should be recommended for even mild symptoms or once left ventricular dilatation occurs. Mitral valve replacement is usually with a mechanical valve. Tissue valves in the mitral position have a relatively short life (sometimes only 5 to 7 years).

Mitral valve prolapse (systolic click–murmur syndrome)

This is the most common heart lesion in the community (3% of adults) and is more common in women. When it occurs in men it is more likely to progress to cause significant regurgitation.

DYNAMIC AUSCULTATION

The click murmur is affected by the:

1.

Valsalva manoeuvre (decreases preload) – murmur longer, click earlier

2.

handgrip (increases afterload) or squatting (increases preload) – murmur shorter.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

There is now thought to be a considerable variation in the normal range of the appearance of the mitral leaflets on echocardiography. Some redundancy of one or both leaflets is commonly seen in normal people. Prolapse of a leaflet of 1 cm or more into the left atrium behind the attachment point of the valve is considered abnormal. Antibiotic prophylaxis, however, is not necessary for these patients unless mitral regurgitation is detected on Doppler interrogation.

ASSOCIATIONS

1.

Marfan’s syndrome.

2.

ASD (secundum).

COMPLICATIONS (MORE COMMON FOR MEN WITH MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE)

1.

Mitral regurgitation.

2.

Infective endocarditis.

Arrhythmias, embolism and sudden death are probably not complications of mitral valve prolapse.

Aortic regurgitation

CAUSES OF CHRONIC AORTIC REGURGITATION

Valvular

1.

Rheumatic (rarely the only murmur in this case).

2.

Congenital (e.g. bicuspid valve; ventral septal defect (VSD) – an associated prolapse of the aortic cusp is not uncommon).

3.

Seronegative arthropathy, especially ankylosing spondylitis.

Aortic root (murmur may be maximal at the right sternal border)

1.

Marfan’s syndrome.

2.

Aortitis (e.g. seronegative arthropathies, rheumatoid arthritis, tertiary syphilis).

3.

Dissecting aneurysm.

4.

Old age.

CAUSES OF ACUTE AORTIC REGURGITATION

Note:

Murmur may be soft because of increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

1.

Valvular – infective endocarditis.

2.

Aortic root – Marfan’s syndrome, hypertension, dissecting aneurysm.

CLINICAL SIGNS OF SEVERITY IN CHRONIC AORTIC REGURGITATION

1.

Collapsing pulse.

2.

Wide pulse pressure.

3.

Length of the

decrescendo

diastolic murmur.

4.

Third heart sound (left ventricular).

5.

Soft aortic component of the second heart sound (A2).

6.

Austin Flint murmur (a diastolic rumble caused by limitation to mitral inflow by the regurgitation jet).

7.

Left ventricular failure.

HINT

A loud systolic murmur, rarely with a thrill, may be present in patients with severe aortic regurgitation without any organic aortic stenosis being associated. The peripheral signs of aortic regurgitation are the clue that this is the real lesion in this situation.

RESULTS OF INVESTIGATIONS

1.

ECG – left ventricular hypertrophy (diastolic overload).

2.

Chest X-ray film:

a.

left ventricular dilatation

b.

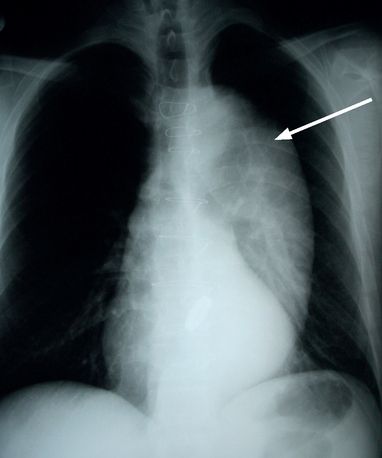

aortic root dilatation or aneurysm (see

Fig 16.11

)

FIGURE 16.11

Massive dilatation of the thoracic aorta (arrow) is seen in this patient with Marfan’s syndrome and aortic regurgitation. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

c.

valve calcification.

3.

Echocardiography:

a.

left ventricular dimensions and function

b.

Doppler estimation of size of regurgitant jet

c.

vegetations (endocarditis can be a cause of acute aortic regurgitation)

d.

aortic root dimensions

e.

valve cusp thickening or prolapse.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

1.

Symptoms – dyspnoea on exertion.

2.

Worsening left ventricular function, such as low ejection fraction (in aortic regurgitation this is increased until late, severe disease intervenes) measured on a gated blood pool scan.

3.

Progressive left ventricular dilatation on serial echocardiograms: left ventricular end-systolic dimension of >5.5 cm.

Aortic stenosis

Valve area: 1.5–2.0 cm

2

. Significant stenosis at <1 cm

2

. In critical aortic stenosis, less than 0.7 cm

2

/m

2

or a valve gradient >70 mmHg.

CAUSES

1.

Degenerative senile calcific aortic stenosis (the most common cause in the elderly).

2.

Rheumatic (rarely isolated).

3.

Calcific bicuspid valve.

CLINICAL SIGNS OF SEVERITY

1.

Plateau pulse.

HINT

The pulse character has been shown not to be useful in elderly patients; this fact may need to be put tactfully to the examiners.

2.

Aortic thrill (very important sign of severe stenosis).

3.

Length, harshness and lateness of the peak of the systolic murmur.

4.

Fourth heart sound (S4).

5.

Paradoxical splitting of the second heart sound (delayed left ventricular ejection and aortic valve closure).