Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (73 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

3.

Pick up the patient’s hand. While feeling the radial pulse, ask whether you may take the blood pressure. The examiners will usually expect you to take the blood pressure.

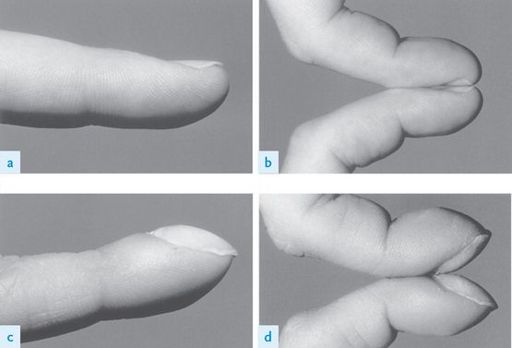

Inspect the patient’s hands for clubbing. Demonstrate Schamroth’s sign (

Fig 16.1

) to the delight of the examiners. If there is no clubbing, opposition of the index finger (nail to nail) demonstrates a diamond shape; in clubbing this space is lost. Also look for the peripheral stigmata of infective endocarditis. Splinter haemorrhages are common (and are usually caused by trauma), whereas Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions (

Fig 16.2

) are rare. Look quickly, but carefully, at each nail bed, otherwise it is easy to miss key signs. Note the presence of an intravenous cannula and, if an infusion is running, look at the bag to see what it is. There will usually be a peripheral or central line in situ if the patient is being treated for infective endocarditis. Note any tendon xanthomata (type II hyperlipidaemia).

FIGURE 16.1

Lateral views of the index finger and Schamroth’s sign in a healthy individual (a) and (b), and in an individual with severe clubbing (c) and (d). L M Taussig, L I Landau.

Pediatric respiratory medicine

, 2nd edn.

Fig 10-3

. Mosby, Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

FIGURE 16.2

Janeway lesions. Based on G L Mandell, J A Bennett, R Dolin.

Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases

, 7th edn. Fig 195-15. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2009, with permission.

HINT

Radiofemoral delay should be assessed very quickly or not at all, unless the stem suggests the patient has hypertension (or you find hypertension when taking the blood pressure).

4.

The pulse at the wrist should be timed for rate and rhythm. Pulse character is poorly assessed here. This is also the time to feel for radiofemoral delay (which occurs in coarctation of the aorta) and radial–radial inequality.

5.

Next inspect the face. Look at the eyes briefly for jaundice (valve haemolysis) and xanthelasma (type II or III hyperlipidaemia) (

Fig 16.3

). You may also notice the classic ‘mitral facies’ (owing to dilatation of malar capillaries associated with severe

mitral stenosis and caused by pulmonary hypertension and a low cardiac output). Then inspect the mouth using a torch for a high-arched palate (Marfan’s syndrome and the possibility of aortic regurgitation and mitral valve prolapse), petechiae and the state of dentition (endocarditis). Look at the tongue or lips for central cyanosis.

FIGURE 16.3

Xanthelasma. M Yanoff, J S Duker.

Ophthalmology

, 3rd edn. Fig 12-9-18. Mosby, Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

6.

The neck is very important, so take time to examine here. The jugular venous pressure (JVP) must be assessed for height and character (see

Table 16.2

and

Fig 16.6

). Use the right internal jugular vein to assess this. Look for a change with inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign).

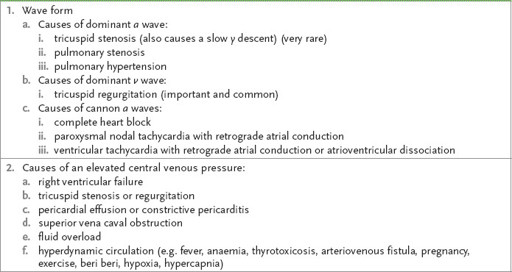

Table 16.2

JVP

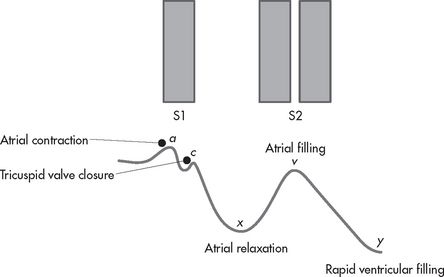

FIGURE 16.6

The JVP and its relationship to the first (S1) and second (S2) heart sounds.

7.

Now feel each carotid pulse separately (never together!). Assess the pulse character (see

Table 16.3

).

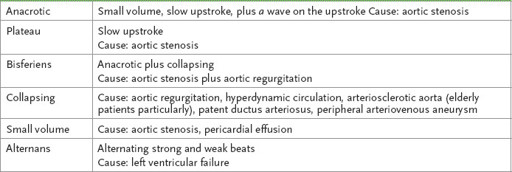

Table 16.3

Arterial pulse character

8.

Proceed to the chest. Look

everywhere

for scars. Previous mitral valvotomy may have been performed by a submammary or lateral thoracotomy approach. These patient slowly redevelop mitral stenosis over many years. Inspect for deformity, the site of the apex beat and visible pulsations. Do not forget about pacemaker and cardioverter-defibrillator boxes (

Fig 16.5

).

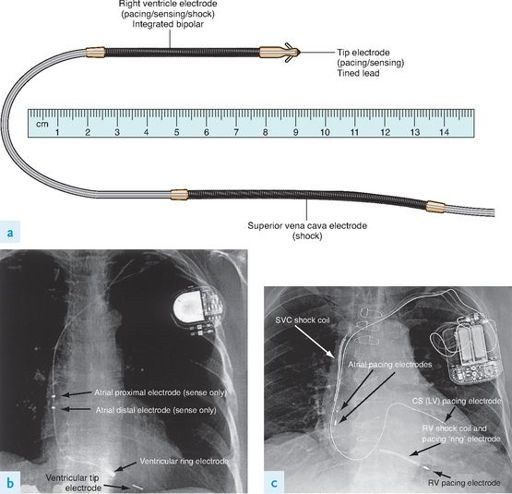

FIGURE 16.5

Pacemaker.

A conventional single lead pacemaker, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), and a right ventricular (RV) defibrillator lead. (a) Conventional pacemaker with one quadripolar lead that provides atrial and ventricular sensing and ventricular pacing. (b) Defibrillator system with biventricular pacing capability. Note that three leads: a conventional bipolar lead to the right atrium, a multipolar lead to the right ventricle, and a unipolar lead to the coronary sinus (CS). The bipolar lead in the right atrium will perform both sensing and pacing function. Likewise, the tip electrode in the right ventricle along with the shock coil performs RV pacing and sensing function. (c) Integrated bipolar RV defibrillator lead. The tip of this lead becomes enmeshed in the RV trabeculae (called a ‘tined’ lead) rather than engaging the myocardial wall with a screw (‘active fixation’). R D Miller.

Miller’s anesthesia

, 7th edn. Fig 43-1. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2010, with permission.

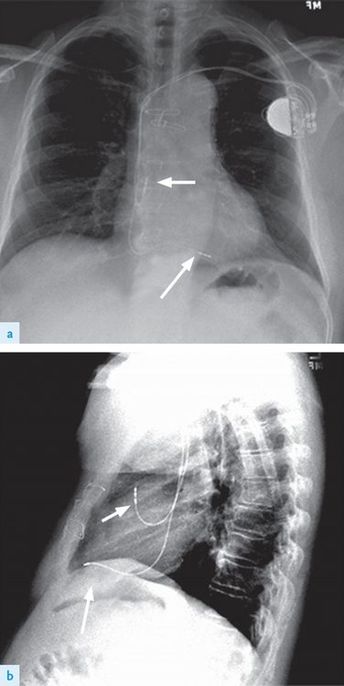

FIGURE 16.4

Chest radiographs (a) and (b), PA and lateral of a pacemaker. The atrial pacing lead (arrowhead) and the ventricular pacing lead (arrow) are smaller in diameter and less radiopaque than the leads associated with an ICD. P E Parson, J P Wiener-Kronish.

Critical care secrets

, 5th edn. Figs 18.2a and b. Mosby, Elsevier, 2013, with permission.

HINT

Mitral valvotomy scars (under the left or right breast) can be quite lateral and easily missed (with ghastly repercussions in the test).

9.

Palpate for the apex beat position. Be seen to count down the correct number of intercostal spaces. The normal position is the fifth intercostal space, 1 cm medial to the midclavicular line. The character of the apex beat is important. There are a number of types.