Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (78 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Note:

Alcohol consumption and obesity are associated with essential hypertension.

2.

Next, confirm that the blood pressure is elevated. Ask to measure it in both arms, and with the patient both lying and standing. Measurement in the legs in a young patient may be important.

3.

Feel the radial pulse and very carefully feel for radiofemoral delay. Palpate for radial–radial asymmetry and inspect both hands for vasculitic changes.

4.

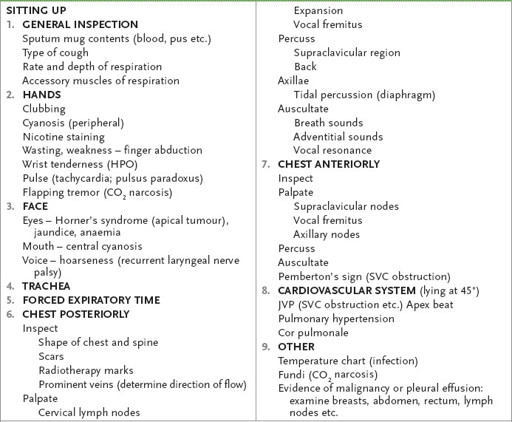

Now look at the face. Inspect the conjunctivae for injection (polycythaemia), and then examine the fundi for hypertensive changes (see

Table 16.7

). Describe what you see when presenting, rather than just giving a grade (

Fig 16.20

).

Table 16.7

Fundoscopy changes in hypertension

| GRADE | CHANGES |

| Grade I | Silver wiring |

| Grade II | Above change plus arteriovenous nipping |

| Grade III | Above changes plus haemorrhages (characteristically flame-shaped) and exudates: soft exudates, also called cotton wool spots, owing to ischaemia; hard exudates owing to lipid residues from leaky vessels |

| Grade IV | Above changes plus papilloedema |

FIGURE 16.20

(a) Hypertensive retinopathy grade 3. Note the flame-shaped haemorrhages and cottonwool spots. (b) Hypertensive retinopathy grade 4. Note AV nipping, sliver wiring and papilloedema. N Talley, S O’Connor,

Clinical examination

, 7th edn. Figs 7.4, 7.5. Elsevier Australia, 2013, with permission. Courtesy of Dr Chris Kennedy and Prof. Ian Constable. Copyright Lion’s Eye Institute, Perth.

5.

Examine the rest of the cardiovascular system, looking especially for left ventricular failure and coarctation of the aorta. Usually a fourth heart sound is present in severe hypertension.

6.

The abdomen should be examined for renal masses, adrenal masses and an abdominal aneurysm. Auscultate for renal bruits (as a result of fibromuscular dysplasia or atheroma). These may have a diastolic component. Listen first just to the right or left of the midline above the umbilicus. Then sit the patient up and

listen in the flanks (a systolic–diastolic bruit in the costovertebral area suggests a renal arteriovenous fistula).

7.

At the end, ask for the results of urine analysis (signs of renal disease). Also remember that cerebrovascular accidents, secondary to hypertension, may cause other physical signs.

Marfan’s syndrome

‘This 37-year-old man has a heart murmur. Please examine him.’

Method

Fortunately, you notice a Marfanoid habitus.

1.

While performing your normal cardiovascular examination, look also for the following signs.

a.

Hands and arms

. Look for arachnodactyly (spider fingers) and joint hypermobility, as well as long, thin limbs.

b.

Face

. You may notice a long and narrow face. Look for lens dislocation or lens replacement. The sclerae may be blue. Look in the mouth for a high-arched palate.

c.

Chest

. Note any pectus carinatum or excavatum.

d.

Heart

. Auscultate for aortic regurgitation and mitral valve prolapse. Also look for the signs of dissecting aneurysm or coarctation of the aorta.

e.

Back

. Look for kyphoscoliosis and hypermobility.

2.

At the end, always ask to measure the arm span, which will exceed the height. The upper segment to lower segment ratio will be less than 0.85 (the upper segment is from the crown to the symphysis pubis and the lower segment is from the symphysis pubis to the ground).

Investigations

1.

Many of these patients will have had serial echocardiograms because the detection of progressive aortic root dilatation will warn of an increased risk of dissection before this occurs.

2.

A slit-lamp examination may be required to diagnose lens dislocation.

Oedema

‘This 70-year-old man has oedema. Please assess him.’

Method

1.

First, stand back and look at the patient. Note whether the oedema is localised or generalised and whether it is gravitational or not.

2.

Assess nutrition quickly (as hypoalbuminaemia and also beri beri owing to vitamin B

1

deficiency can cause oedema). Also, any obvious signs of myxoedema must never be missed.

3.

If necessary, ask the patient to undress as appropriate and then further define the areas affected. Palpate for pitting. Proceed, depending on your findings (see

Table 16.8

).

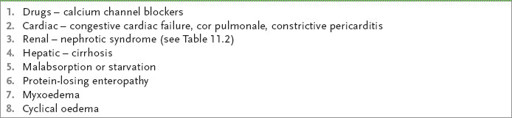

Table 16.8

Causes of oedema

PITTING LOWER LIMB OEDEMA

1.

Define the extent of the oedema.

2.

Look for signs of DVT (2 cm difference in calf swelling, prominent superficial veins and increased warmth have minor diagnostic value; Homans’ sign is unhelpful). Note the presence of varicose veins (a common cause of mild peripheral oedema) and the presence of vein-harvesting scars (for coronary artery surgery).

3.

Feel the inguinal nodes. Go to the abdomen and look for abdominal wall oedema, prominent abdominal wall veins (inferior vena caval obstruction), ascites, any abdominal masses and evidence of liver disease. A pulsatile liver (tricuspid regurgitation) or malignant involvement should be particularly looked for.

4.

Next examine the JVP. Then examine for signs of right ventricular failure and constrictive pericarditis. Feel all the node groups.

5.

Finally examine for delayed ankle jerks (to exclude hypothyroidism) and look at the urine analysis. Remember that vasodilating drugs used for hypertension or angina are very common causes of oedema.

NON-PITTING LOWER LIMB OEDEMA

Consider the various causes, including lymphoedema (from malignant infiltration, congenital disease, filariasis, Milroy’s disease) and myxoedema.

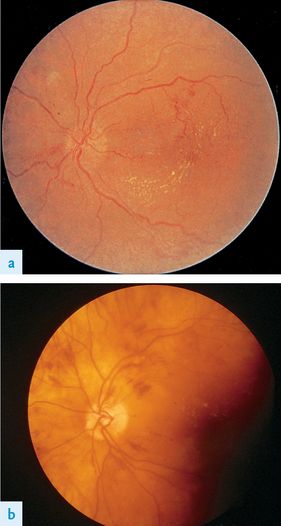

SUPERIOR VENA CAVAL OBSTRUCTION (SEE

Table 16.9

,

Fig 16.21

)

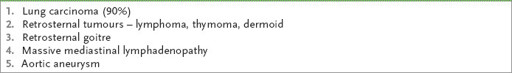

Table 16.9

Causes of superior vena caval obstruction

FIGURE 16.21

Superior vena cava obstruction in bronchial carcinoma. Note the swelling of the face and neck and the development of collateral circulation in the veins of the chest wall. L Goldman, A I Schafer.

Goldman’s Cecil medicine

, 24th edn. Fig 99.6. Elsevier, 2012, with permission.

1.

The patient may appear Cushingoid, from either a tumour or treatment with steroids. Note the plethoric cyanosed face with periorbital oedema. There may be exophthalmos and conjunctival injection.

2.

Examine the pupils: a mass in the chest may have caused Horner’s syndrome.

3.

Examine the fundi for venous dilation. Examine the neck, which is enlarged. The JVP is raised, but the vein is not pulsatile.

4.

Decide whether the thyroid gland is enlarged. Check Pemberton’s sign (p. 371,

Fig 16.42

).

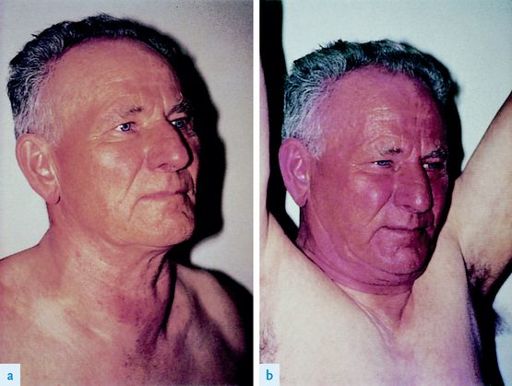

FIGURE 16.42

(a) and (b) Positive Pemberton’s sign M H Swartz.

FACP – Textbook of physical diagnosis: history and examination

, 6th edn. Fig #1.#2Figs 9.14A and B, Elsevier, 2009, with permission.

5.

Feel for supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and listen over the trachea for inspiratory stridor.

6.

Examine the chest carefully for distended venous collaterals.

7.

One or both arms may be oedematous.

8.

Look for all the peripheral manifestations of lung carcinoma.

The respiratory system

The respiratory examination

‘This 69-year-old man presented with breathlessness. Please examine him.’

Method (see

Table 16.10

)

Table 16.10

Respiratory system examination