Folklore of Yorkshire (2 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

I

t is an incongruity often observed that the most acute phase of witch hysteria in England occurred not in the Middle Ages – commonly decried as the zenith of scientific ignorance and superstition – but in the first half of the seventeenth century, even as the first seeds of the Enlightenment were being sown. There is ample evidence to suggest that Yorkshire was as much embroiled in the witch craze as any other region, but whilst there were undoubtedly a number of associated executions in the county, there were no episodes as egregious as the Pendle Witch Trials which gripped neighbouring Lancashire in 1612, or ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins’ reign of terror in East Anglia from 1644 to 1646.

Yorkshire’s most famous witch-hunt occurred around Washburndale in 1621 and was amply documented by its instigator in the pamphlet ‘A Discourse on Witchcraft as it was acted in the family of Mr. Edward Fairfax of Fewston in the County of York in the year 1621

AD

’. Fairfax was an accomplished writer whose work was praised by future Poet Laureate John Dryden, but it seems that he possessed a misanthropic disposition which often brought him into conflict with his less educated neighbours after he inherited Newhall at Fewston (now submerged beneath Swinsty Reservoir) from his father in 1600. His contempt for them is clear throughout his work: ‘Such a wild place,’ he writes, ‘Such rude people upon whose ignorance God have mercy!’

Doubtless the locals regarded Fairfax with similar disdain, and, by 1621, tensions erupted in accusations of witchcraft. Fairfax charged eight Fewston women with working enchantments on his three daughters, Ellen, Elizabeth and Ann: he claimed they had caused the girls to suffer from fits, trances, ‘irrational behaviour’ and, on one occasion, temporary blindness. Meanwhile, every minor misfortune the family suffered, Fairfax did not hesitate to attribute to witchcraft. For instance, when Elizabeth fell from an insecure haymow and injured herself, he perceived it to be the work of Bess Fletcher, who was watching the child at the time. His suspicions were only confirmed when Ann died of natural causes during infancy.

Fairfax also claimed to have evidence of the alleged witches’ malefic intent. Supposedly an old widow named Margaret Thorpe had been seen casting images of his daughters into a stream; lamenting if they floated, but cheering if they sank. Perhaps most fancifully, he accused the women of abducting his daughters and forcing them to attend a Midsummer’s Eve bonfire on the surrounding moors – a superstitious and possibly pagan survival which to Fairfax’s Puritanical mind was identical with diabolism. However, to the credit of the local authorities – including Fewston’s vicar, Henry Greaves – all such ‘evidence’ was dismissed as circumstantial or hearsay and Fairfax twice failed to have the women convicted at York Assizes. Following their release, the women held a great celebration in Timble Gill, over which Fairfax insisted the Devil himself had presided.

Contrary to popular belief, this is how most witch trials concluded. Although accusations of witchcraft were rife in the seventeenth century, only 30 per cent of those indicted were actually convicted. The spate of such allegations around that time was largely due to familiar social tensions heightened by the febrile religious atmosphere that followed the Reformation. As social historian Keith Thomas notes, whilst the Reformation had aimed to purge Christianity of superstitious practices, it actually heightened superstitious dread amongst the majority of the population. Protestantism emphasised the power of the Devil, yet by prohibiting the characteristically Catholic rite of exorcism, simultaneously removed the ordinary person’s best defence against his work. As such, paranoia increased but it could only now be defused through the secular courts rather than harmless religious ritual.

The Reformation also brought about a change in attitude towards the poor. Whilst Catholicism had stressed the religious importance of almsgiving through the Middle Ages, Protestantism was much more individualistic and exalted the idea of self-reliance. This exacerbated social conflict, increasing ill-feeling on both sides of the divide: the poor resented the new mercantile class for their reluctance to give alms, whilst the merchants resented the poor for begging for them. The potential consequence of this dynamic can be seen in the Heptonstall witch trial of 1646. In the week before Michaelmas, Elizabeth Crossley had been refused alms at the house of Henry Cockroft and left muttering imprecations. Thus, when Cockroft’s infant son began to suffer fits two nights later, from which he eventually died, the finger of blame was pointed straight at Crossley.

But whilst Elizabeth Crossley was probably just an innocent beggar with a temper, the issue was compounded by the fact that some outsiders who were otherwise ostracised by the community exploited their reputation for witchcraft in order to gain some modicum of deference from their neighbours. Their perceived power was the art of ‘maleficium’ – causing harm to people or property through the use of sorcery. It was essentially ‘black magic’, as opposed to the ‘white magic’ practiced by ‘wise’ men and women, whose skills were primarily directed towards healing, finding lost items and defence against maleficium. Yet when the charms of such people failed – for instance, if a potion they had administered to cure an illness was coincidentally followed by the death of the patient – it was easy for such people to be accused of maleficium themselves.

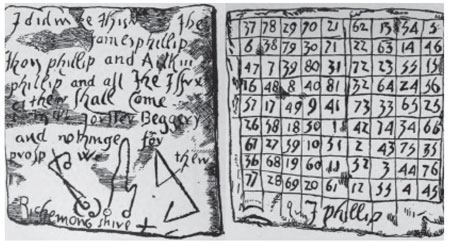

Gatherley Moor Witch Tables.

Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that rare individuals may have offered malefic services. In the nineteenth century, two lead tablets dated to 1575 were found buried in a tumulus on Gatherley Moor. They were described as ‘quadrangular with several planetary marks, rude scratches and an inscription on one side; and on the other are figures set in arithmetical proportion from 1 to 81 and so disposed in parallel and equal ranks, that the sum of each row, as well diagonally and horizontally as perpendicularly is equal to 369.’ The inscription states that these ‘witch tables’ were spells to cause the Philips family to flee Richmondshire or forever fail to prosper there and as they were signed by John Philips, this unambiguous act of maleficium must have arisen from a family dispute, possibly over the terms of a will.

By the end of the seventeenth century, belief in witchcraft was dying out amongst the educated classes. The last executions for the ‘crime’ occurred in Exeter in 1682 and its definition was revised by the 1735 Witchcraft Act, so that the offence became one of fraud rather than harmful intent. In Yorkshire, the trend was no different: even evangelically religious sources were growing sceptical about such accusations and in May 1683, the radical nonconformist preacher, Reverend Oliver Heywood, scathingly dismissed the concerns of a member of his Calderdale congregation who feared her twelve-year-old son had been bewitched. Yet despite the increasingly enlightened attitudes of learned authorities, amongst the general population fear of witchcraft persisted well into the nineteenth century and Victorian folklorists recorded countless such narratives in their county collections.

North Yorkshire was blessed with two prodigious collectors of witch lore during this period: Reverend J.C. Atkinson of Danby and Richard Blakeborough of Ripon, whose books provide a relatively reliable and comprehensive survey of witch belief in rural North Yorkshire at the time. Fear of maleficium causing injury to individuals does not seem to have been as rife as it was during the seventeenth century, doubtless helped by improved understanding of the causes of illness. Nonetheless, witches were still widely credited with the ability to adversely affect somebody’s fortune and their livelihood. Equally, they were still identified with outsiders in the community, especially the friendless or destitute, who have always acted as scapegoats for any misfortune and were perceived to leech on the prosperity of the more industrious.

It is, therefore, not surprising that one of the principle crimes witches were imagined to commit was milk-stealing. In rural communities, dairy-farming was one of the cornerstones of the private economy and the subsistence of a household greatly depended upon its herd, so when the cows produced less than their expected yield for natural reasons such as infertility or mastitis, a scapegoat was required. Moreover, as J.C. Atkinson observes, prior to the passing of the Enclosure Acts between 1750 and 1860, livestock was grazed on common pasture and milk-stealing was a genuine problem which resulted in numerous court actions. Doubtless if a culprit could not be identified, then blame would be projected onto a witch.

Witches were ascribed the power of shape-shifting and supposed to go about their milk-stealing business in a variety of animal guises. Nancy Newgill of Broughton, for instance, not only changed into the form of a hedgehog and sucked the milk from cows’ udders overnight; she also had power over other hedgehogs in the district to encourage them to do the same. Meanwhile, shortly after the herd belonging to a farmer at Alcomden above Calderdale ran dry, he woke in the night to find a strange black cat watching him for the end of his bed. He threw a knife at the intruder and struck its foreleg, which caused it to scamper away. The following day a neighbour remarked that he had seen old Sally Walton of Clough Foot near Widdop with her arm in a sling, and the farmer understood who had been bewitching his cattle in the night.

However, the milk-stealing, shape-shifting witch was most commonly associated with the hare. Like hedgehogs, hares are solitary, nocturnal feeding animals which might often have been seen in pastures after dark; unlike hedgehogs, they have a connection with magic extending into the pre-Christian past and an uncanny countenance that can disarm many. When a farmer in Commondale near Guisborough feared that a witch named ‘Au’d Molly’ was milking his cattle dry, he received advice to watch overnight in the field and carry a shotgun loaded with silver bullets, for nothing else could disable such a supernatural creature. But upon its arrival in the field, the witch-hare stalked up to the farmer and gave him such a stare with its piercing eyes that he turned heel and fled!

Sometimes the hare is not the witch herself but her familiar, albeit one with which the sorcerer is so intimately connected that injury to it has a corresponding effect on its mistress. This was the case at Eskdale where a drove of hares were causing great mischief by feeding on the saplings in a new plantation. The steward managed to cull them all except for one, which continued to evade both hound and bullet; he was subsequently advised to use silver slugs in his gun and with this contingency he finally succeeded in putting an end to the beast. At that moment, some distance away, an old woman with an evil reputation flung up her hands as she was carding wool and cried, ‘They have shot my familiar spirit!’ whereupon she fell to the floor dead.

The witch does not seem to have taken the form of a hare only to steal milk; in many tales, she seems to adopt such a guise for the sheer pleasure of it. In an archetypal narrative from Westerdale on the North York Moors, a party of hare-coursers encounter a witch simply known as ‘Nanny’. She asks them how their sport is going and when the men reply that they haven’t seen a single hare all day, she tells them of a field in which they might find just such an animal, one bound to give them a fine chase. They must only promise that they will not hunt it with a black dog. All members of the party agree to this stipulation and Nanny proceeds to tell them where this superior specimen of a leporid can be found.

Sure enough, the party find the hare in the place Nanny described, and they pursue it the length and breadth of the dale, never gaining upon it. But just as they are once more drawing near to the point where they started, a stray black dog joins the chase. It proves fleeter than any of their hounds and so little by little, it closes in on the hare until they reach the vicinity of Nanny’s cottage. The hare makes straight for a cavity in the cottage walls but squeezes through it just a little too late, as the black dog manages to bite a chunk out of the hare’s flank before it can get fully into the hole. The party of coursers is mortified: they know and fear Nanny’s reputation, and are concerned about how she will react if she finds out that her injunction was broken, so they enter her cottage to explain. Within, they find Nanny lying on her bed, bleeding profusely from a wound on her haunch.

The tale is told of many witches in several different localities, such as Peg Humphreys of Bilsdale or Peggy Flaunders of Marske-by-the-Sea. Indeed, it is a classic example of a migratory legend known throughout the British Isles and much of northern Europe, the motif now categorised by folklorists as ‘The Witch Who Was Hurt’. In Yorkshire, there are some minor local variations worth mentioning. For instance, the witch Abigail Craister, who dwelled in a cave on Black Hambleton, is said to have evaded pursuit by leaping from Whitestone Cliff into the waters of Gormire Lake below and re-emerged from a sinkhole some nine miles away. Her ghost is thought to haunt the vicinity of the lake still and can be seen riding over Kilburn on her broomstick.