Folklore of Yorkshire (7 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

The hints which exist are tantalising but not conclusive, primarily stemming from the notoriously unreliable study of toponymy. For instance, on Cringle Moor in Cleveland there is a tumulus known as Drake Howe, the name of which is thought to derive from the Old English term for a dragon. There is also a legend that treasure is buried within the mound. However, no surviving narrative explicitly connects a dragon with the treasure, and as Chapter 11 shows, associations between ancient earthworks and treasure are not at all uncommon in Yorkshire, so this may have nothing to do with a dragon at all. Attempts have also been made to connect the legend of a ‘Golden Cradle’ buried in the earthworks of Castle Hill above Huddersfield to a dragon suggested by the nearby toponym ‘Wyrmcliffe’.

However, as so many toponyms have been subject to centuries of consonantal drift, it is difficult to say with confidence to what it originally referred and a great deal of wishful thinking has been exhibited by amateur philologists over the years. An example of the controversial nature of such speculation can be seen in Reverend H.N. Pobjoy’s attempt to derive the name of Blakelaw, a vanished hamlet that once stood on Hartshead Moor in West Yorkshire, from the Old English

Dracanhlawe

, meaning ‘Mound of the Dragon’. He sought to connect this with vague rumours of a dragon legend he’d heard amongst the locals of his parish. Yet another, arguably more authoritative source, prefers to give it as

Blachelana

, which has the prosaic translation of ‘black hill’.

Where detailed dragon legends do survive in Yorkshire, they all conform to a single type. These beasts are invariably voracious and destructive, but do not guard treasure. Nor does it take theft to incite them to terrorise the surrounding countryside – rather such aggression is intrinsic to their nature. Furthermore, whilst Anglo-Saxon dragons were usually located in wild, remote and ancient places – Beowulf’s dragon resides in ‘a steep stone burial mound high on the heath – in most surviving local legends a dragon’s habitat is typically located on the borders of civilisation and their lairs close to a settlement.

Jacqueline Simpson also observes that dragon tales are ‘characteristic of either coastal areas or of river valleys, and preferably of areas where hills are fairly low’. This is especially true of Yorkshire, where the majority of narratives are concentrated in the fertile, woody and relatively low-lying areas of the county, particularly Cleveland, the Vale of York and the South Yorkshire Coalfield. There are no dragons to be found in the heart of the Pennines, although what this geographical distribution says about the origin, spread and function of such legends remains unclear.

It must equally be noted that most Yorkshire dragons fail to conform to the image of a dragon as it is understood today. Although their breath is often noisome and poisonous, it is not fiery and perhaps more significantly, some examples may be described as possessing wings, but they are never reported to fly. They more typically resemble a gigantic snake – coiling up in their den and crawling along the ground, often killing their victims in the manner of a boa constrictor. Indeed, in many cases the beasts are referred to as ‘worms’ or ‘serpents’ in the original sources of the narrative.

Similarly, these monsters rarely capture or feast on young maidens as in the legend of St George and its ilk. The only place in Yorkshire with which this motif is associated is Handale. More often they simply exhibit such an insatiable appetite as to place a serious burden on the neighbouring farmers’ livelihoods. Kellington’s dragon devoured flocks of sheep, Wantley’s stole cattle and tore up trees, whilst Sexhow’s demanded the milk of nine cows daily. Meanwhile, at Filey – in one of the most original dragon legends to have emerged from Yorkshire – the dragon’s unappeasable appetite is successfully used against it.

The most famous and well-developed dragon legend in Yorkshire is that of the Dragon of Wantley, and this provides a vivid retelling of the template from which all such narratives in the county (with the exception of one) seem to have been drawn. The Wantley story survives in such detail largely because it was immortalised as a popular ballad, which circulated widely as a printed broadside in the seventeenth century. The earliest surviving version comes from 1685, titled ‘An Excellent Ballad of the Dreadful Combat Fought between Moore of Moore-Hall and the Dragon of Wantley’ and it was subsequently included in the 1794 edition of Bishop Percy’s seminal collection

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry

.

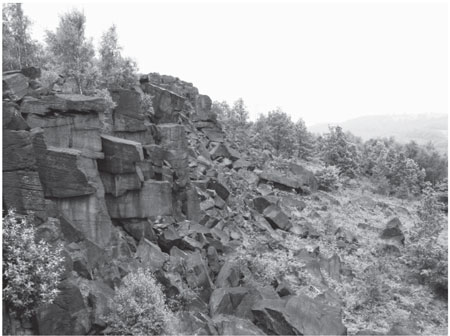

Although no such place as ‘Wantley’ exists in the county, the name is generally agreed to have arisen from a corruption of the village of Wortley and the nearby Wharncliffe Crags in South Yorkshire’s Don Valley, a supposition supported by the ballad’s correspondence with the topography of that area. The ballad relates that the dragon made its home amongst a hilltop escarpment, supposed to be Wharncliffe Crags, and from its den there ravaged the locality – devouring livestock, trees, houses and children, all whilst polluting the air with its hot, stinking breath. It often stopped at a well to drink, where it turned the water to ‘burning brandy’.

The folk of the vicinity were so traumatised by the dragon’s merciless assaults that they were forced to beg the aid of a ‘furious knight’ known as Moore of Moore-Hall. The ballad makes Moore himself sound like a scarcely less terrifying prospect than the dragon; a bawdy, hell-raising type who once in anger swung a horse by the tail and mane until it was dead, and then proceeded to eat its carcass! Still, there was probably no better hope to defeat such a beast as the dragon and Moore assented, on the sole condition that he was sent a sixteen-year-old girl to ‘anoint him’ overnight before the combat and dress him in the morning.

Wharncliffe Crags above the Don Valley, once home to the famed Wantley Dragon. (Kai Roberts)

Despite his formidable strength, Moore realised that the dragon was more than an equal to him in might alone, so decided to rely on cunning to defeat it. To this end he had the steelworkers of Sheffield forge him a suit of armour covered in spikes so that the dragon could not grapple with him, and then hid in the well from which the beast was wont to drink in order to ambush it. Despite Moore’s element of surprise, the two opponents were evenly matched and their struggle lasted for two days and a night, with neither receiving so much as a wound. Finally, however, Moore delivered a lucky blow to the only vulnerable spot on the dragon’s body – noted in earlier, less sanitised versions of the ballad as its anus – at which the monster fell down and expired.

Whilst this ballad displays all the classic themes of a Yorkshire dragon narrative, many scholars have erroneously stated that the ballad is not an authentic local legend but actually a polemic against a historical landowner. The suggestion originates with Godfrey Bosville, a correspondent of Bishop Percy, whose theory was included as a footnote in

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry

. Bosville asserted that the ballad satirised a late sixteenth-century legal case in which Sir Francis Wortley and his tenants were embroiled over payment of tithes. According to this reading, Sir Francis is personified as the voracious dragon and Moore of Moore-Hall as the lawyer sent by the tenants to do battle with him.

Later, in his 1819

History of Hallamshire

, the esteemed antiquarian Reverend Joseph Hunter conjectured that the ballad could refer to another dispute earlier in the sixteenth century, which arose when Sir Thomas Wortley attempted to depopulate Wharncliffe Chase to create a personal hunting ground. Yet whilst these theories have been uncritically repeated by commentators on the legend ever since, doubt was cast as early as 1864 by the local historian John Holland. Although it might be true that there was considerable antagonism between the Wortley family and their tenants during the sixteenth century, there is no evidence whatsoever to indicate that the ballad is meant to satirise these conflicts, beyond the jesting tone of the lyrics and much wishful thinking.

Considering that the story of the Dragon of Wantley is identical to a dragon-slaying narrative associated with various locations across Yorkshire (with minor local variations), it would be an insult to the skill of any balladeers to suggest that they could not have been any more inventive. It seems far more probable that this migratory legend was already attached to Wantley, along with many other sites in the county, and the composer took his inspiration from it. Whilst this does not necessarily rule out the possibility that the ballad displays satirical intent, the narrative is simply too consistent with a wider dragon-slaying tradition to suggest that it was invented solely for that purpose.

It is particularly damning to Bosville’s case that the Moore family had left Moore Hall (located near Wharncliffe Crags in the Ewden Valley) half a century before the legal case the ballad is supposed to parody, and not one member of that line was ever recorded as a lawyer. Indeed, the connection between the Moore family and dragons appears to be much older than the sixteenth century. The family was associated with the area from the Norman Conquest at least and a dragon was featured on their family coat of arms. Meanwhile, there is a prominent stone effigy of a dragon in the medieval Church of St Nicholas at High Bradfield – of which the Moore family were patrons.

A dragon also features on the coat of arms of the Latimer family whose ancestral home was located at Well near Ripon, and there is a vague local legend to the effect that one of their ancestors slew such a beast at a spot between Well and Tanfield. This association between heraldry and dragons may well offer a clue as to the origin of some local dragon legends, casting them as back-formations designed to explain the choice of that particular motif in a noble family’s coat of arms. Dragons were commonly employed in medieval heraldry as a symbol of power and an association with dragon-slaying was especially favoured in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when the cult of St George was at its height in England.

As such, folklorists agree that a number English dragon stories represent ‘charter legends’ – narratives which arose to justify the origin and persistence of some social custom. In these cases, tales of dragon-slaying may have evolved to explain why a local landowning family were entitled to hold their position: namely that one of their ancestors had displayed great courage and valour in slaying a dragon which preyed on their tenants’ livelihoods and children. Such a story painted the noble family as men of character, with the implication that the local community should continue to be thankful that such men had saved them from a ravening menace and remained in a position to do so again in the future, should circumstances demand it.

A similar moral can be detected in the story of Sir William Wyvill, a fourteenth-century landowner who reputedly slew a dragon that tormented the region of Slingsby in the Vale of York. However, the only narrative in which the connection between dragon-slaying and ancestral estates is made explicit is the legend of the dragon of Handale in Cleveland. This monster liked to ‘beguile young damsels from the paths of truth and duty, and afterwards feed on their dainty limbs.’ It was killed by a local lad called Scaw, who subsequently married an Earl’s daughter he rescued from the beast’s lair and thereby eventually came into possession of her father’s lands. Yet, ironically, Scaw does not seem to have been an historical individual and the name may instead have been derived from a local toponym.

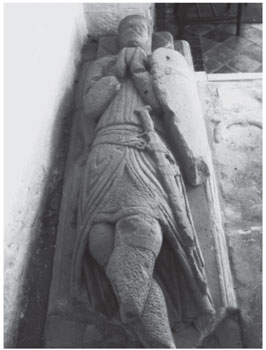

Nonetheless, a stone coffin supposedly belonging to Scaw was once shown in the ruins of Handale Priory and such alleged memorials are another common feature of dragon legends in Yorkshire. A similar stone coffin lid can be seen in the Church of St Edmund at Kellington, near Pontefract; it is said to commemorate Armroyd, the shepherd who with the help of his dog dispatched a sheep-killing dragon in that region. The stone appears to feature representations of a serpent and a dog, whilst a weathered carving of a cross was once thought to represent his shepherd’s crook. Supposed effigies of dragon-slayers can also be seen in the churches at Slingsby and Nunnington. In both cases, the legend attached to the effigy is the same and given the geographical proximity of the two villages, it is agreed that the legends probably stem from a single source.