Folklore of Yorkshire (5 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

When an individual was suffering from an illness believed to be the result of maleficium, a witch-bottle was used. Typically, the hair, fingernails and urine of the target was placed with a great quantity of pins or nails in an earthenware jar which was then heated over a fire. Again, it was believed that the link an enchantment established between a witch and her victim was such that this tactic would cause great pain to her. It was imagined she would feel the heat from the fire and the symbolic stabbing of the pins, and she would be forced to reverse the initial spell to spare herself this agony. Her only other hope of release was for the jar to shatter during the heating process or if she could get to it herself and destroy it.

Often this would also have the effect of identifying the malefactor. One story relates that when the child of a Halifax family fell ill, the above procedure was followed and the witch-bottle was left to heat on the fire overnight. During the early hours of the morning, there was a rap at the door and outside stood the notorious Auld Betty in an evident state of distress. She asked if they needed their fire ‘riddling’ (to sieve out the ash) but unfortunately such a transparent attempt to access the house and destroy the witch-bottle was immediately recognised. She was chased from the door and shortly thereafter, the child began to recover, suggesting Auld Betty had been forced to lift her spell.

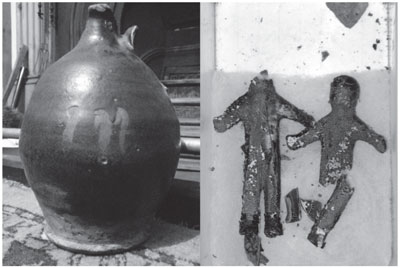

A typical witch-bottle was unearthed around 1960 at Halton East, near Skipton, buried upside down in a field, apparently far from the nearest habitation. It was found to hold several lumps of clay, each one pierced through; altogether there were thirty-five pins, twenty-two nails and sixteen needles. This location was unusual, however. More often witch-bottles were placed in the fabric of the building or beneath the threshold to preserve the household from further mischief and they have frequently been discovered in such contexts many years later. A particularly unique example was discovered in the 1970s, buried beneath the doorstep of an outbuilding attached to a seventeenth-century farmhouse at Ogden, near Halifax. The jar contained some form of liquid, which could well have been urine, and two fragile clay figurines, doubtless intended to represent the bewitched individuals.

It is quite common for other magically protective artefacts to be found in the fabric of old buildings, especially near threshold locations such as doorways, windows, chimneys and eaves. Such items are described as ‘apotropaic’ meaning ‘to ward off evil’. Amongst the most common discoveries were old shoes, which have been turned up in such large quantities and in such unusual locations that accidental deposition can be ruled out. Nobody has yet produced a convincing explanation as to why old shoes were regarded as an appropriate defence against evil. In a study of apotropaic practices, archaeologist Ralph Merrifield suggested that they were ‘considered an effective trap for an evil spirit’, based on a fourteenth-century legend concerning a Buckinghamshire priest who cast the Devil into an old boot.

A witch-bottle discovered at Ogden near Halifax. (Kai Roberts)

Not quite as ubiquitous but rather more memorable is the desiccated cat. These are usually discovered in airtight cavities in the walls of seventeenth-century buildings, where they were deliberately placed and allowed to starve or suffocate. Sometimes they have even been fixed in position to simulate a cat on the hunt. It is not entirely clear how widespread this practice was, as such finds are inadequately recorded. Often workmen assume they were simply an animal that got trapped and dispose of them; or else, understanding their possible significance, replace them in the wall when the work is complete. Nonetheless, it appears that it was not a purely secular custom, as a desiccated cat was discovered in the roof of the Church of St Thomas a Becket at Heptonstall when it was demolished in 1875.

Again, the exact function of desiccated cats remains debatable. Some deflationary historians have suggested they were merely intended to deter rats and mice. However, as Ralph Merrifield notes, ‘As such it was hardly less superstitious, with its quasi-magical imitation of a hunting cat. It is also possible that the real fear underlying the practice was spiritual rather than actual rodents.’ It was a familiar principle of magical thinking that ‘like affects like’ and considering the preference of witches for feline familiars, people may have believed a totem cat represented the building’s best defence against such attack. This would certainly explain why desiccated cats are found at vulnerable threshold points such as chimneys and roofs.

The use of desiccated cats has also been associated with the practice of foundation sacrifice. There is abundant archaeological evidence to suggest that nearly all the pre-Christian cultures of the British Isles made ritual offerings to guarantee the fortune of a new building, the remains of which were typically deposited in the foundations. Animals were the most common sacrifice, and the placing of horse-skulls in this context continued for many centuries – as another discovery at Halton East attests. But there are also indications that humans were occasionally used in such a fashion; and whilst such grisly practices are often thought to be a relic of pagan superstition, the principle of foundation sacrifice may have persisted well into the Middle Ages.

In 1895, renovation work was undertaken on the medieval tower of St Luke and All Saints’ Church at Darrington, near Pontefract, following damage during a storm. The

Yorkshire Herald

reported:

It was found that under the west side of the tower, only about a foot from the surface, the body of a man had been placed in a sort of bed in the solid rock, and the west wall was actually resting on his skull … The grave must have been prepared and the wall placed with deliberate intention upon the head of the person buried, and this was done with such care that all remained as placed for at least six hundred years.

Although this individual may not have been deliberately killed for the purpose, it certainly suggests that the power of human remains to ensure the luck of a building did not die out with the conversion of Britain to Christianity.

Indeed, the cult of relics was an archetypal feature of medieval Catholicism and whilst this orthodox doctrine may not have extended to the apotropaic use of human remains in secular contexts, there was undoubtedly a continuum between the two. Yorkshire has several examples of human skulls being used for apotropaic purposes and although these traditions primarily seem to date from the seventeenth century and beyond, it is possible that their roots go much deeper. The use of the skull as opposed to any other bone is easy enough to understand; many cultures regard the skull as the seat of the soul and there is extensive evidence to suggest that the image of the head itself is frequently considered apotropaic in magical thinking. Certainly it reinforces the image of watchful guardianship and such relics are often referred to as ‘guardian skulls’.

The most famous example in the county is the skull known as ‘Owd Nance’, kept at Burton Agnes Hall in East Yorkshire. Local folklore relates that this mansion was built during the reign of Elizabeth I by three sisters named Frances, Margaret and Anne Griffith. Anne was the youngest and the most enthusiastic about the project, but tragically before the building was complete, she was attacked by robbers whilst travelling home one night and mortally wounded. On her death bed, she made her surviving sisters promise that following her death they would remove her skull and give it a position of honour in the new Hall. Frances and Margaret solemnly agreed to Anne’s request, but failed to fulfil the vow once she had passed away.

Burton Agnes Hall in East Yorkshire, home of a guardian skull known as Owd Nance. (Kai Roberts)

As a result, their lives were made a misery for the next two years as their new home was wracked by terrible moans and other uncanny noises. No servant would remain in their employment and eventually they were forced to have their late sister’s corpse exhumed. Her skull was removed and placed on a table in a position of honour in the Hall. The belief developed that as long as ‘Owd Nance’ remained undisturbed, the building and its occupants would enjoy good fortune. However, should the skull be displaced or slighted in any way, dire consequences were sure to follow. One story claims that a maid, sick of the skull’s macabre presence and sceptical of its supposed power, threw the offending item on a loaded wagon outside. At once ‘the horses plunged and reared, the house shook, pictures fell,’ and the skull was returned to its proper position forthwith.

Owd Nance’s unnerving visage was never particularly appreciated by the residents of Burton Agnes and during the nineteenth century, Sir Henry Boynton (a descendant of the Griffith sisters) had it bricked up in the wall, ensuring that it could no longer disturb the residents, nor could it ever be removed. The precise location of the skull today remains a closely guarded secret, although it is variously believed to be above a doorway in one of the upper corridors, or behind the fireplace of the Queen’s State bedroom in the north wing. The latter room is also rumoured to be haunted by a ghost thought to be that of Owd Nance. According to one source, ‘She still appears occasionally and generally in the month of October, which is supposed to have been the month of her death. She is short, slight and dressed in fawn colour.’

The only difficulty is that whilst the existence of the skull is never doubted, the legend of its origin appears to be entirely fictitious. Burton Agnes Hall was built in 1601 for Sir Henry Griffith and besides a portrait of dubious provenance known as ‘The Three Miss Griffiths’, there is no historical record of an Anne Griffiths in the family during this period. It raises the possibility that the skull may have been a much older relic brought to Burton Agnes by the Griffith family when they moved from their native Wales in the thirteenth century. There would certainly be precedent for such a conclusion: the guardian skull kept at Bettiscombe Manor in Dorset, which local tradition asserted belonged to a West Indian servant who worked there during the seventeenth century, actually proved to be the remains of a prehistoric woman, some three to four thousand years old.

Although Burton Agnes is the most famous case, several other examples of guardian skulls exist in Yorkshire and bad luck invariably follows their removal. During the early nineteenth century, a skull was discovered in a lead box concealed behind the fireplace of Sowood House at Coley, near Halifax. It was given a Christian burial in the local churchyard, but the tenants of Sowood were subsequently disturbed by nocturnal cries of ‘Where’s my head?’ and forced to return the skull to its original position to bring the trouble to an end. Unfortunately, the skull was revealed yet again during renovations in the 1960s and passed to the police for investigation, since which time its whereabouts have been impossible to ascertain. A specimen was also recorded at Lund Manor House in East Yorkshire, but this too was walled up and no narratives relating to it survive.

Sowood House, where a guardian skull was uncovered in the 1960s. (Kai Roberts)

Traditions continue to be attached to such artefacts even in the modern period. Hull’s Ye Olde White Harte Inn has a skull on permanent display in its bar, believed to have been discovered at the hostelry in the late nineteenth century. It appears to have belonged to a youth and a fracture in the bone suggests its owner may have died from a blunt blow to the head. Various stories have arisen to account for this fact: one version suggests the skull belonged to a boy who was murdered by a drunken sea captain and his body concealed under the staircase; another account claims the skull is that of a serving maid who maybe committed suicide or was murdered following a liaison with the landlord and her corpse concealed in the attic. Either way, it is believed bad luck will befall the pub should the skull ever be removed from the building.