Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (46 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

2.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

20) was to ensure that people with learning disabilities would ‘

. . . have the choice to have relationships, become parents and continue to be parents . . .

,’ with the expectation of their being supported in doing so. Therefore, midwives should use their skills to coordinate the care of these mothers in partnership with them recognising their dignity, their abilities and love for their children (DH/Partnerships for Children, Families & Maternity 2007; Commissioning Board Chief Nursing Officer & DH Chief Nursing Adviser 2012). This care should be supportive rather than judgemental, or paternalistic, assessing the needs of women, their babies and the wider family and acting to achieve their best interests.

Parenting styles and expert advice

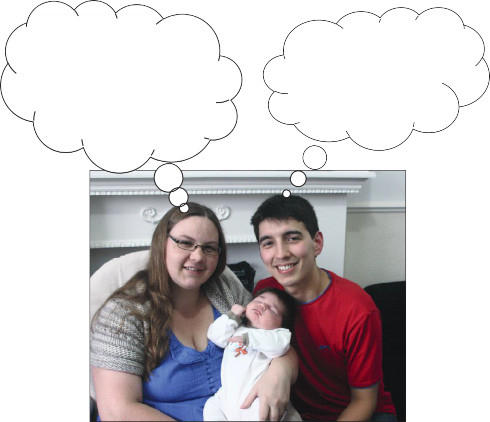

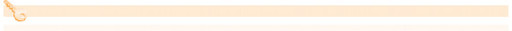

All new parents are faced with multiple decisions about how to care for their newborn babiesfrom abundant information and advice from multiple sources (see Figure 5.17). Until relatively recently parenting was the preserve of parents and their families, involving close friends, col- leagues and peers (Fatherhood Institute 2008; Smith 2010). Kinship networks and peers exert influence based on geographical, practical and personal considerations. Parenting expectations

How often should I feed him? Should I use cloth nappies or disposables? Some of my friends use dummies,but I’m not sure.Where should he sleep? How do we avoid colic? Can we spoil him by cuddling him too much?

How often should I feed him? Should I use cloth nappies or disposables? Some of my friends use dummies,but I’m not sure.Where should he sleep? How do we avoid colic? Can we spoil him by cuddling him too much?

Figure 5.17

Examples of choices faced by new parents.are shaped by culture (e.g. the tradition among Chinese women ‘Tso-Yueh-Tzu’ or ‘doing-the- month’) involving a range of practices in the first month after childbirth to restore women’s strength. This is characterised by ‘confinement and convalescence’ leading to acknowledgment and compensation for childbearing (Chien et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2014). Midwives may encounter other customs such as the circumcision of male infants (Ingram et al. 2003) and must approach these sensitively, ensuring that their advice is evidence-based, with the welfare of the mothers and infants uppermost.Information and advice also flows from statutory health professionals such as midwives, GPs, health visitors and obstetricians (NICE 2010). There are now many ‘

expert

’ voices from which parents may choose, either through direct contact, or numerous media formats. These include traditional print media, broadcast media (such as radio and television) and electronic media including blogs, podcasts, social media and mobile phone applications (Robinson and Jones 2014). Parents may perceive any of these as authoritative voices, influencing their parenting styles.

Routine/schedule based style

Some parents highly value structure and certainty and are keen to establish schedules and routines for their babies. Well-intentioned medical experts such as 18th century physician, Dr William Cadogan and early 20th century public health specialist, Frederick Truby-King contrib- uted such advice (Palmer 2009). Both men promoted breastfeeding of babies by their mothers; however, greatly fearing the danger of overfeeding, they advocated very restrictive feeding schedules, forbidding overnight feeding (Palmer 2009). One modern day counterpart, ex-maternity nurse Gina Ford, in her ‘Contented Baby with Toddler book,’ dictates a schedule for babies (and by extraction for their parents) incorporating the timing of nappy changes, the frequency, duration and time-of-day for infant feeding and sleeping (Ford 2009). Prescriptive schedules may provide a sense of security for parents who value predictability in their postnatal lives, but may rely on rather paternalistic and anecdotal premises rather than sound research evidence. For example Cadogan believed that the care and preservation of children should be in the hands of

men

of good sense, since:

. . . this business has been too long fatally left to the management of women, who cannot be supposed to have proper knowledge to fit them for such a task . . .

111(Cadogan 1748, p. 2)Strict, non-evidence-based routines may also negate maternal–infant physiological and psy- chosocial interactions, blunting parental responses to distressed infants (see Chapter 4: ‘Psy- chology applied to maternity care’). Indeed, Ford (2009) does not warn of potential harm to maternal milk supply and infant immune sensitisation, by introducing formula feeds (see Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’). Midwives working with parents wishing to adopt routine approaches should only reinforce positive aspects which may be gleaned, such as creating a distinction between day and night through managing the environment (e.g. venue, lighting, and noise) (NHS Choices 2012). However, they should clearly explain where strict adherence to routine conflicts with sound evidence, in order to allow parents to make an informed choice and to ensure the baby’s wellbeing.

111(Cadogan 1748, p. 2)Strict, non-evidence-based routines may also negate maternal–infant physiological and psy- chosocial interactions, blunting parental responses to distressed infants (see Chapter 4: ‘Psy- chology applied to maternity care’). Indeed, Ford (2009) does not warn of potential harm to maternal milk supply and infant immune sensitisation, by introducing formula feeds (see Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’). Midwives working with parents wishing to adopt routine approaches should only reinforce positive aspects which may be gleaned, such as creating a distinction between day and night through managing the environment (e.g. venue, lighting, and noise) (NHS Choices 2012). However, they should clearly explain where strict adherence to routine conflicts with sound evidence, in order to allow parents to make an informed choice and to ensure the baby’s wellbeing.

Attachment parenting

Another approach to parenting is attachment parenting, which includes granting the baby unlimited access to his or her parents, is characterised by closeness of proximity between the112

baby and his or her mother (in the main) and breastfeeding in response to infant cues. Devices such as slings or baby carriers are used and the baby is held frequently in his or her parents’ arms. Aspects of this approach have some support in studies in relation to lactation physiology, infant immunology and maternal and infant bonding (Klaus and Kennell 1982; Colson et al. 2003; 2008; Chiu et al. 2005: see Chapters 4 and 10). However, it may sometimes be difficult for parents to fully accommodate this approach, due to lifestyle constraints. Potential problems occur with such aspects as co-sleeping. Co-sleeping is considered to be an independent risk factor for increase in the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) for all babies (Blair et al. 2009; Carpenter et al. 2013), but this is disputed and contextualised by others (Ball 2009; UNICEF UK 2013). Some aspects of bonding and attachment theory have been incorporated into contemporary UK maternity care. Women are supported to have their babies placed in skin-to-skin contact with them, soon after birth; babies room-in with their mothers throughout the day and night in maternity units, enabling mothers to respond to their babies’ cues (NICE 2006). Additionally, a measure for the prevention of SIDS is for the baby to sleep in his or her parents’ bedroom for the first six months of life (NHS Choices 2012) (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where the prevention of SIDS is also discussed).

baby and his or her mother (in the main) and breastfeeding in response to infant cues. Devices such as slings or baby carriers are used and the baby is held frequently in his or her parents’ arms. Aspects of this approach have some support in studies in relation to lactation physiology, infant immunology and maternal and infant bonding (Klaus and Kennell 1982; Colson et al. 2003; 2008; Chiu et al. 2005: see Chapters 4 and 10). However, it may sometimes be difficult for parents to fully accommodate this approach, due to lifestyle constraints. Potential problems occur with such aspects as co-sleeping. Co-sleeping is considered to be an independent risk factor for increase in the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) for all babies (Blair et al. 2009; Carpenter et al. 2013), but this is disputed and contextualised by others (Ball 2009; UNICEF UK 2013). Some aspects of bonding and attachment theory have been incorporated into contemporary UK maternity care. Women are supported to have their babies placed in skin-to-skin contact with them, soon after birth; babies room-in with their mothers throughout the day and night in maternity units, enabling mothers to respond to their babies’ cues (NICE 2006). Additionally, a measure for the prevention of SIDS is for the baby to sleep in his or her parents’ bedroom for the first six months of life (NHS Choices 2012) (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where the prevention of SIDS is also discussed).

Pragmatic parenting

A different approach to parenting was advocated by psychoanalyst Winnicott who spoke of ‘good enough’ parenting:

. . . The good enough ‘mother’ (not necessarily the infant’s own mother) is one who makes active adaptation to the infant’s needs, an active adaptation that gradually lessens, accord- ing to the infant’s growing ability to account for failure of adaptation and to tolerate the results of frustration . . .

(Winnicott 1953, p. 94)Good enough parenting is a more pragmatic approach to parenting seen in parents who, prioritise and meet their children’s needs, providing consistent care and routine, whilst engag- ing help from relevant services when problems are identified (Kellett and Apps 2009). This approach contains flexibility and allows parents to incorporate positive and evidence-based, aspects from a range of parenting styles.

Key points

Key points

. . . have the choice to have relationships, become parents and continue to be parents . . .

,’ with the expectation of their being supported in doing so. Therefore, midwives should use their skills to coordinate the care of these mothers in partnership with them recognising their dignity, their abilities and love for their children (DH/Partnerships for Children, Families & Maternity 2007; Commissioning Board Chief Nursing Officer & DH Chief Nursing Adviser 2012). This care should be supportive rather than judgemental, or paternalistic, assessing the needs of women, their babies and the wider family and acting to achieve their best interests.

Parenting styles and expert advice

All new parents are faced with multiple decisions about how to care for their newborn babiesfrom abundant information and advice from multiple sources (see Figure 5.17). Until relatively recently parenting was the preserve of parents and their families, involving close friends, col- leagues and peers (Fatherhood Institute 2008; Smith 2010). Kinship networks and peers exert influence based on geographical, practical and personal considerations. Parenting expectations

How often should I feed him? Should I use cloth nappies or disposables? Some of my friends use dummies,but I’m not sure.Where should he sleep? How do we avoid colic? Can we spoil him by cuddling him too much?

How often should I feed him? Should I use cloth nappies or disposables? Some of my friends use dummies,but I’m not sure.Where should he sleep? How do we avoid colic? Can we spoil him by cuddling him too much?Figure 5.17

Examples of choices faced by new parents.are shaped by culture (e.g. the tradition among Chinese women ‘Tso-Yueh-Tzu’ or ‘doing-the- month’) involving a range of practices in the first month after childbirth to restore women’s strength. This is characterised by ‘confinement and convalescence’ leading to acknowledgment and compensation for childbearing (Chien et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2014). Midwives may encounter other customs such as the circumcision of male infants (Ingram et al. 2003) and must approach these sensitively, ensuring that their advice is evidence-based, with the welfare of the mothers and infants uppermost.Information and advice also flows from statutory health professionals such as midwives, GPs, health visitors and obstetricians (NICE 2010). There are now many ‘

expert

’ voices from which parents may choose, either through direct contact, or numerous media formats. These include traditional print media, broadcast media (such as radio and television) and electronic media including blogs, podcasts, social media and mobile phone applications (Robinson and Jones 2014). Parents may perceive any of these as authoritative voices, influencing their parenting styles.

Routine/schedule based style

Some parents highly value structure and certainty and are keen to establish schedules and routines for their babies. Well-intentioned medical experts such as 18th century physician, Dr William Cadogan and early 20th century public health specialist, Frederick Truby-King contrib- uted such advice (Palmer 2009). Both men promoted breastfeeding of babies by their mothers; however, greatly fearing the danger of overfeeding, they advocated very restrictive feeding schedules, forbidding overnight feeding (Palmer 2009). One modern day counterpart, ex-maternity nurse Gina Ford, in her ‘Contented Baby with Toddler book,’ dictates a schedule for babies (and by extraction for their parents) incorporating the timing of nappy changes, the frequency, duration and time-of-day for infant feeding and sleeping (Ford 2009). Prescriptive schedules may provide a sense of security for parents who value predictability in their postnatal lives, but may rely on rather paternalistic and anecdotal premises rather than sound research evidence. For example Cadogan believed that the care and preservation of children should be in the hands of

men

of good sense, since:

. . . this business has been too long fatally left to the management of women, who cannot be supposed to have proper knowledge to fit them for such a task . . .

111(Cadogan 1748, p. 2)Strict, non-evidence-based routines may also negate maternal–infant physiological and psy- chosocial interactions, blunting parental responses to distressed infants (see Chapter 4: ‘Psy- chology applied to maternity care’). Indeed, Ford (2009) does not warn of potential harm to maternal milk supply and infant immune sensitisation, by introducing formula feeds (see Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’). Midwives working with parents wishing to adopt routine approaches should only reinforce positive aspects which may be gleaned, such as creating a distinction between day and night through managing the environment (e.g. venue, lighting, and noise) (NHS Choices 2012). However, they should clearly explain where strict adherence to routine conflicts with sound evidence, in order to allow parents to make an informed choice and to ensure the baby’s wellbeing.

111(Cadogan 1748, p. 2)Strict, non-evidence-based routines may also negate maternal–infant physiological and psy- chosocial interactions, blunting parental responses to distressed infants (see Chapter 4: ‘Psy- chology applied to maternity care’). Indeed, Ford (2009) does not warn of potential harm to maternal milk supply and infant immune sensitisation, by introducing formula feeds (see Chapter 10: ‘Infant feeding’). Midwives working with parents wishing to adopt routine approaches should only reinforce positive aspects which may be gleaned, such as creating a distinction between day and night through managing the environment (e.g. venue, lighting, and noise) (NHS Choices 2012). However, they should clearly explain where strict adherence to routine conflicts with sound evidence, in order to allow parents to make an informed choice and to ensure the baby’s wellbeing.Attachment parenting

Another approach to parenting is attachment parenting, which includes granting the baby unlimited access to his or her parents, is characterised by closeness of proximity between the112

baby and his or her mother (in the main) and breastfeeding in response to infant cues. Devices such as slings or baby carriers are used and the baby is held frequently in his or her parents’ arms. Aspects of this approach have some support in studies in relation to lactation physiology, infant immunology and maternal and infant bonding (Klaus and Kennell 1982; Colson et al. 2003; 2008; Chiu et al. 2005: see Chapters 4 and 10). However, it may sometimes be difficult for parents to fully accommodate this approach, due to lifestyle constraints. Potential problems occur with such aspects as co-sleeping. Co-sleeping is considered to be an independent risk factor for increase in the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) for all babies (Blair et al. 2009; Carpenter et al. 2013), but this is disputed and contextualised by others (Ball 2009; UNICEF UK 2013). Some aspects of bonding and attachment theory have been incorporated into contemporary UK maternity care. Women are supported to have their babies placed in skin-to-skin contact with them, soon after birth; babies room-in with their mothers throughout the day and night in maternity units, enabling mothers to respond to their babies’ cues (NICE 2006). Additionally, a measure for the prevention of SIDS is for the baby to sleep in his or her parents’ bedroom for the first six months of life (NHS Choices 2012) (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where the prevention of SIDS is also discussed).

baby and his or her mother (in the main) and breastfeeding in response to infant cues. Devices such as slings or baby carriers are used and the baby is held frequently in his or her parents’ arms. Aspects of this approach have some support in studies in relation to lactation physiology, infant immunology and maternal and infant bonding (Klaus and Kennell 1982; Colson et al. 2003; 2008; Chiu et al. 2005: see Chapters 4 and 10). However, it may sometimes be difficult for parents to fully accommodate this approach, due to lifestyle constraints. Potential problems occur with such aspects as co-sleeping. Co-sleeping is considered to be an independent risk factor for increase in the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) for all babies (Blair et al. 2009; Carpenter et al. 2013), but this is disputed and contextualised by others (Ball 2009; UNICEF UK 2013). Some aspects of bonding and attachment theory have been incorporated into contemporary UK maternity care. Women are supported to have their babies placed in skin-to-skin contact with them, soon after birth; babies room-in with their mothers throughout the day and night in maternity units, enabling mothers to respond to their babies’ cues (NICE 2006). Additionally, a measure for the prevention of SIDS is for the baby to sleep in his or her parents’ bedroom for the first six months of life (NHS Choices 2012) (see Chapter 8: ‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where the prevention of SIDS is also discussed).Pragmatic parenting

A different approach to parenting was advocated by psychoanalyst Winnicott who spoke of ‘good enough’ parenting:

. . . The good enough ‘mother’ (not necessarily the infant’s own mother) is one who makes active adaptation to the infant’s needs, an active adaptation that gradually lessens, accord- ing to the infant’s growing ability to account for failure of adaptation and to tolerate the results of frustration . . .

(Winnicott 1953, p. 94)Good enough parenting is a more pragmatic approach to parenting seen in parents who, prioritise and meet their children’s needs, providing consistent care and routine, whilst engag- ing help from relevant services when problems are identified (Kellett and Apps 2009). This approach contains flexibility and allows parents to incorporate positive and evidence-based, aspects from a range of parenting styles.

Key points

Key pointsParents are diverse.

Midwives mainly support and care for childbearing women and their infants but also fathers andthe wider family.

Other books

Bridge for Passing by Pearl S. Buck

The Spoilers / Juggernaut by Desmond Bagley

The Sherlockian by Graham Moore

Maggie's Breakfast by Gabriel Walsh

Deep Into the Abyss (Darkest Faerie Tale Series Book 2) by Riley Bancroft

Star Road by Matthew Costello, Rick Hautala

Cora's Pride (Wilderness Brides Book 1) by Peggy L Henderson

Love Scars - 1: Scratch by Lane, Lark

Roses in Autumn by Donna Fletcher Crow

Bound to Be His (The Archer Family Book 2) by Allison Gatta