Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (14 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

2.28Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Unfortunately for Reynolds, these “gentlemen” had the final say. Before the sailing date, he was dismissed from the post, and did not accompany the expedition that was largely his creation. It had partly to do with an ongoing antipathy on the part of the Navy to having civilians of any stripe aboard their ships; also, as delay began to follow delay, with the appropriation rapidly dwindling, Reynolds had been making his opinions known a little too loudly, and got on the wrong side of Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson. But the dismissal also showed the hand of Charles Wilkes, the expedition’s eventual leader, who had been clashing with Reynolds ever since the aborted 1828 effort.

28

From here on, perhaps understandably after such disappointment as a reward for such prolonged effort, Reynolds’ interests shifted away from the sea. He continued to write about earlier adventures—two such pieces appeared in the

Southern Literary Messenger,

in 1839 and 1843, and “Mocha Dick” in

Knickerbocker

in 1839—but he devoted the rest of his life to law and politics.

28

From here on, perhaps understandably after such disappointment as a reward for such prolonged effort, Reynolds’ interests shifted away from the sea. He continued to write about earlier adventures—two such pieces appeared in the

Southern Literary Messenger,

in 1839 and 1843, and “Mocha Dick” in

Knickerbocker

in 1839—but he devoted the rest of his life to law and politics.

In 1840 he hit the boards in Connecticut as a campaign speaker for the Whigs, and in 1841 began a law firm on Wall Street, where he worked primarily on maritime law. In 1848, ever entrepreneurial, he organized a stock company for a mining operation in Leon, Mexico. The sketch of Reynolds in

The History of Clinton County Ohio

concludes: “He was elected president of the company, and, after a few years of persistent effort, he made quite a success in the field; but his health soon failed, and he died near New York City in 1858, aged fifty-nine years. He was buried in that city.”

The History of Clinton County Ohio

concludes: “He was elected president of the company, and, after a few years of persistent effort, he made quite a success in the field; but his health soon failed, and he died near New York City in 1858, aged fifty-nine years. He was buried in that city.”

Poe liked Reynolds and the address so much that he stole parts of it for

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,

whose opening chapters were published serially in the January and February 1837 issues of the

Southern Literary Messenger.

Poe also lifted details from Reynolds’s earlier

Voyage of the Potomac.

Reynolds wasn’t alone in the honor. Poe ransacked existing seagoing literature for his tale about Pym, appropriating left and right, and returned to Symmes’ Hole for his big finale.

29

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,

whose opening chapters were published serially in the January and February 1837 issues of the

Southern Literary Messenger.

Poe also lifted details from Reynolds’s earlier

Voyage of the Potomac.

Reynolds wasn’t alone in the honor. Poe ransacked existing seagoing literature for his tale about Pym, appropriating left and right, and returned to Symmes’ Hole for his big finale.

29

Poe’s timing in writing

Pym

showed his good commercial instincts—he was a magazine editor, after all. The voyage had captured the national imagination and was just under way when Poe’s novel came out, which left him free to cook up the grisly possibilities he envisioned for his own Antarctic excursion. Even so, the book didn’t sell very well, and Poe returned to the shorter work at which he was far more accomplished.

Pym

showed his good commercial instincts—he was a magazine editor, after all. The voyage had captured the national imagination and was just under way when Poe’s novel came out, which left him free to cook up the grisly possibilities he envisioned for his own Antarctic excursion. Even so, the book didn’t sell very well, and Poe returned to the shorter work at which he was far more accomplished.

Literary historian Alexander Cowie summed up

Pym

as “a plotless, nightmare-ridden book.” Right on both counts, but it nonetheless holds a certain fascination, however morbid. For all its faults, which are many, it is a lot of gruesome fun. A seeker of extreme sensation in life, it makes sense that Poe would push every boundary he could think of in his writing. One literary form of pushing limits is parody, and

Pym

is arguably that as well, a ghastly gothic send-up of that literary staple, the journal of a polar voyage. It bears an uncanny resemblance to one polar voyage in particular—

Symzonia.

A number of scholars have pointed to

Symzonia

as a likely model. In

Pilgrims Through Space and Time

, J. O. Bailey, citing a long list of parallels, suggests that it might have been called

Pymzonia

. But with all its debts to Symzonia—and Poe truly seems to have used it as a template for his own tale—

Pym

takes these elements to the outer limits. And it’s all done deadpan, with a straight face. Poe admired

Robinson Crusoe

for its seeming verisimilitude, and all that ransacking of marine literature, with the occasional outright theft for good measure, at first gives the book the superficial aspect of being just another voyager’s account of his travels; the realistic, matter-of-fact journalistic tone continues as events get more and more outrageous. Poe loved hoaxes, and he does his damnedest in

Pym

to carry it off.

Pym

as “a plotless, nightmare-ridden book.” Right on both counts, but it nonetheless holds a certain fascination, however morbid. For all its faults, which are many, it is a lot of gruesome fun. A seeker of extreme sensation in life, it makes sense that Poe would push every boundary he could think of in his writing. One literary form of pushing limits is parody, and

Pym

is arguably that as well, a ghastly gothic send-up of that literary staple, the journal of a polar voyage. It bears an uncanny resemblance to one polar voyage in particular—

Symzonia.

A number of scholars have pointed to

Symzonia

as a likely model. In

Pilgrims Through Space and Time

, J. O. Bailey, citing a long list of parallels, suggests that it might have been called

Pymzonia

. But with all its debts to Symzonia—and Poe truly seems to have used it as a template for his own tale—

Pym

takes these elements to the outer limits. And it’s all done deadpan, with a straight face. Poe admired

Robinson Crusoe

for its seeming verisimilitude, and all that ransacking of marine literature, with the occasional outright theft for good measure, at first gives the book the superficial aspect of being just another voyager’s account of his travels; the realistic, matter-of-fact journalistic tone continues as events get more and more outrageous. Poe loved hoaxes, and he does his damnedest in

Pym

to carry it off.

But there are hints early on. Before the voyage is under way, the young narrator rhapsodizes about his hopes for the trip: “For the bright side of the painting I had a limited sympathy. My visions were of shipwreck and famine; of death and captivity among barbarian hordes; of a lifetime dragged out in sorrow and tears, upon some grey and desolate rock, in an ocean unapproachable and unknown.” Mind you, this is what he

hopes

will happen. And does he ever get his wish!

hopes

will happen. And does he ever get his wish!

Pym is sneaked onboard by his friend Augustus, deposited as a stowaway in a dark claustrophobic hold, from which he soon finds he cannot get out, beginning the voyage in a sort of burial alive, one of Poe’s favorite terrors. While he’s stuck in this fetid compartment, up on deck the crew is mutinying. For days he nearly starves and goes mad, and is threatened by man’s best friend, a dog trapped in there with him. Finally Augustus springs him. Joined by thuggish-looking half-breed Dirk Peters, the three kill all the mutineers but one and retake the vessel. But, wouldn’t you know it, a protracted gale reduces the ship to a floating wreck, kept from sinking by its buoyant cargo of oil. They can’t get at the food in the hold, so it’s either death by starvation or being washed overboard.

Then a ship approaches with what proves to be an

ex

-crew. “Twenty-five or thirty human bodies, among whom were several females, lay scattered about … in the last and most loathsome state of putrefaction.” On one sits a seagull, “busily gorging itself with the horrible flesh, its bill and talons deeply buried, and its white plumage spattered all over with blood.” A tip of the hat to Coleridge for that scene. Another vessel comes by but doesn’t see them.

ex

-crew. “Twenty-five or thirty human bodies, among whom were several females, lay scattered about … in the last and most loathsome state of putrefaction.” On one sits a seagull, “busily gorging itself with the horrible flesh, its bill and talons deeply buried, and its white plumage spattered all over with blood.” A tip of the hat to Coleridge for that scene. Another vessel comes by but doesn’t see them.

Dirk Peters, as imagined by artist René Clarke, looking cheerfully sinister and ready to rock with his bottle of rum and shiv on his belt, in a 1930 edition produced by Heritage Press for the Limited Editions Club. (© 1930 by The Limited Editions Club [George Macy Companies, Inc.])

Now they’re

really

starving. They begin sizing each other up as possible entrees. They draw lots, and Parker, whose idea it was, gets the short straw. Dirk Peters, living up to his first name, stabs him. For the next four days the others nosh on Parker’s diminishing remains. Finally Pym figures out a way to cut a hole into the storeroom, which is filled with water, so they have to dive repeatedly to bring up whatever they can—a bottle of olives, a bottle of Madeira, and a live tortoise. Augustus has injured his arm, which begins turning black, and he wastes away, a mere forty-five pounds when he dies. When Peters tries to pick him up, one of Augustus’s legs comes off in his hands. Can things get worse? Of course. The hulk rolls over. But the three survivors manage to clamber up on it, and, in one of those ironies that made Poe smile, what do these starving men find on the hull? Plenty of nutritious barnacles. They catch rainwater in their shirts.

really

starving. They begin sizing each other up as possible entrees. They draw lots, and Parker, whose idea it was, gets the short straw. Dirk Peters, living up to his first name, stabs him. For the next four days the others nosh on Parker’s diminishing remains. Finally Pym figures out a way to cut a hole into the storeroom, which is filled with water, so they have to dive repeatedly to bring up whatever they can—a bottle of olives, a bottle of Madeira, and a live tortoise. Augustus has injured his arm, which begins turning black, and he wastes away, a mere forty-five pounds when he dies. When Peters tries to pick him up, one of Augustus’s legs comes off in his hands. Can things get worse? Of course. The hulk rolls over. But the three survivors manage to clamber up on it, and, in one of those ironies that made Poe smile, what do these starving men find on the hull? Plenty of nutritious barnacles. They catch rainwater in their shirts.

It’s brutally hot, but they can’t cool off in the ocean because of the sharks endlessly cruising around them. They’re dying. But then another ship approaches, the

Jane Guy,

and this time they are saved—briefly. This whaler heads farther south, piercing the southern ice barrier into temperate seas. As the climate becomes increasingly warmer—just as it does in

Symzonia

—they come upon an island near the South Pole populated by seemingly friendly savages. But it turns out to be one of the strangest and most sinister islands in literature. Everything, every plant and creature, even the water, is black. The woolly-haired natives even have black teeth—and not from not brushing. White in any form is unknown to them, except for the strange white animal (with red teeth) they worship as a terrible totem. The natives come out to meet the

Jane Guy

in large sea canoes, greeting them with cries of

Anamoo-moo

and

Lama-Lama.

For a few days everything is swell. But then they set an ambush for the crew, killing them in a landslide; they head out in canoes to burn the

Jane Guy,

which proves a miscalculation when the gunpowder in the hold explodes, sending body parts flying. All the crew are dead but Pym and Peters, fortuitously semi-buried alive (again) in a rock chamber during the landslide. They manage to escape in a native canoe, abducting one Nu-Nu to accompany them as a guide, but he proves useless, lying in the canoe bottom writhing in fear and dying a few days later. A persistent current draws their little craft ever southward. A gray vapor is seen rising above the horizon.

Jane Guy,

and this time they are saved—briefly. This whaler heads farther south, piercing the southern ice barrier into temperate seas. As the climate becomes increasingly warmer—just as it does in

Symzonia

—they come upon an island near the South Pole populated by seemingly friendly savages. But it turns out to be one of the strangest and most sinister islands in literature. Everything, every plant and creature, even the water, is black. The woolly-haired natives even have black teeth—and not from not brushing. White in any form is unknown to them, except for the strange white animal (with red teeth) they worship as a terrible totem. The natives come out to meet the

Jane Guy

in large sea canoes, greeting them with cries of

Anamoo-moo

and

Lama-Lama.

For a few days everything is swell. But then they set an ambush for the crew, killing them in a landslide; they head out in canoes to burn the

Jane Guy,

which proves a miscalculation when the gunpowder in the hold explodes, sending body parts flying. All the crew are dead but Pym and Peters, fortuitously semi-buried alive (again) in a rock chamber during the landslide. They manage to escape in a native canoe, abducting one Nu-Nu to accompany them as a guide, but he proves useless, lying in the canoe bottom writhing in fear and dying a few days later. A persistent current draws their little craft ever southward. A gray vapor is seen rising above the horizon.

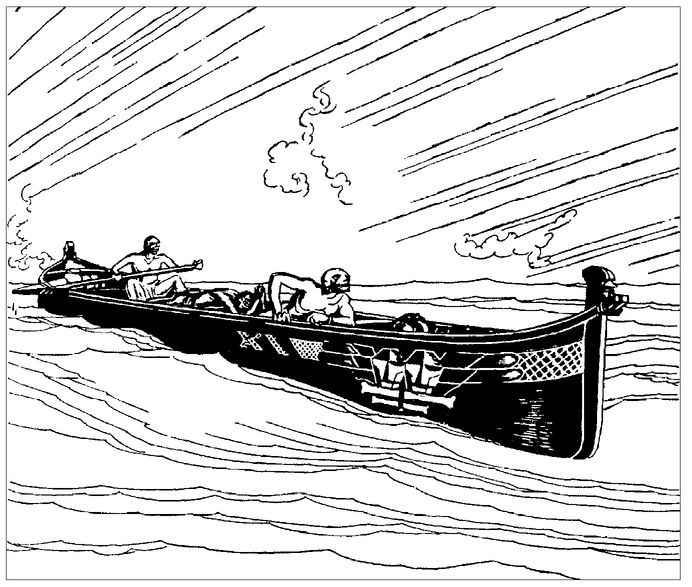

Boat adrift. “The wind had entirely ceased, but it was evident that we were still hurrying on to the southward, under the influence of a powerful current.” (© 1930 by The Limited Editions Club [George Macy Companies, Inc.])

The seawater becomes hot to the touch and takes on a milky hue. “A fine white powder, resembling ashes—but certainly not such—fell over the canoe and over a large surface of the water.” A day later, “the range of vapor to the southward had arisen prodigiously in the horizon, and began to assume more distinctness of form. I can liken it to nothing but a limitless cataract … we were evidently approaching it with a hideous velocity.” Not counting a short afterword, which Poe provides to continue the pose that this has been an actual nonfiction account, these are the final lines:

Many gigantic and pallidly white birds flew continuously now from beyond the veil, and their scream was the eternal

Tekeli-li!

as they retreated from our vision … and now we rushed into the embraces of the cataract, where a chasm threw itself open to receive us. But there arose in our pathway a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men. And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.

Go figure. He says in the afterword that the final two or three chapters have been lost, regrettable because they no doubt “contained matter relative to the Pole itself, or at least to regions in its very near proximity; and as, too, the statements of the author in relation to these regions may shortly be verified or contradicted by means of the governmental expedition now preparing for the Southern Ocean.”

Pym’

s abrupt ending has puzzled and annoyed readers and critics alike. Did Poe simply weary of a bad business, as many have suggested? Could be. But its very abruptness adds a final element of ambiguity missing from the rest of the book. Toward the end Poe begins toying with the symbolic possibilities of whiteness and, less happily, blackness. Critic Leslie Fiedler has argued persuasively that taking his white characters way down south to the all-black island represents southern racist dreaming, nightmare division, a macabre South Seas rendering of that deepest slaveholder dread—a slave insurrection. “The book projects his personal resentment and fear,” says Fiedler, “as well as the guilty terror of a whole society in the face of those whom they can never quite believe they have the right to enslave.”

s abrupt ending has puzzled and annoyed readers and critics alike. Did Poe simply weary of a bad business, as many have suggested? Could be. But its very abruptness adds a final element of ambiguity missing from the rest of the book. Toward the end Poe begins toying with the symbolic possibilities of whiteness and, less happily, blackness. Critic Leslie Fiedler has argued persuasively that taking his white characters way down south to the all-black island represents southern racist dreaming, nightmare division, a macabre South Seas rendering of that deepest slaveholder dread—a slave insurrection. “The book projects his personal resentment and fear,” says Fiedler, “as well as the guilty terror of a whole society in the face of those whom they can never quite believe they have the right to enslave.”

Whiteness doesn’t fare too well either. In

The Power of Blackness,

Harry Levin sees in that final whiteness “a mother-image.” Levin says “the milky water is more redolent of birth than of death; and the opening in the earth may seem to be a regression wombward.” But Fiedler finds in the engulfing womblike whiteness of the cataract a perverse twist on the great mother symbol. Clearly, despite the postscript, Pym and Peters are sucked down to their deaths, and Fiedler sees this final and fatal embracing whiteness as “the Great Mother as

vagina dentata.

” Ouch! And Poe uses Symmes’ Hole to chew up his hapless hero! “From the beginning,” Fiedler says, “a perceptive reader of

Gordon Pym

is aware that every current sentimental platitude, every cliché of the fable of the holy marriage of males is being ironically exposed.”

The Power of Blackness,

Harry Levin sees in that final whiteness “a mother-image.” Levin says “the milky water is more redolent of birth than of death; and the opening in the earth may seem to be a regression wombward.” But Fiedler finds in the engulfing womblike whiteness of the cataract a perverse twist on the great mother symbol. Clearly, despite the postscript, Pym and Peters are sucked down to their deaths, and Fiedler sees this final and fatal embracing whiteness as “the Great Mother as

vagina dentata.

” Ouch! And Poe uses Symmes’ Hole to chew up his hapless hero! “From the beginning,” Fiedler says, “a perceptive reader of

Gordon Pym

is aware that every current sentimental platitude, every cliché of the fable of the holy marriage of males is being ironically exposed.”

Other books

The Unquiet Dead by Gay Longworth

Monsieur Pamplemousse Hits the Headlines by Michael Bond

Sins and Scarlet Lace by Liliana Hart

The Subtle Knife by Philip Pullman

Pretty Baby [Wolf Creek Pack 7] by Stormy Glenn

Gypsy of Spirits: Prequel to So Fell the Sparrow by Jennings, Katie

Shelter by Sarah Stonich

12 Borrowing Trouble by Becky McGraw

Secrets Dispelled by Raven McAllan

Backward Glass by Lomax, David