Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (51 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

When scientists are confronted with this scenario, their standard reply is that in the twentieth century too many medical breakthroughs began with the rich, but eventually benefited the whole population and helped to narrow rather than widen the social gaps. For example, vaccines and antibiotics at first profited mainly the upper classes in Western countries, but today they improve the lives of all humans everywhere.

However, the expectation that this process will be repeated in the twenty-first century may be just wishful thinking, for two important reasons. First, medicine is undergoing a tremendous conceptual revolution. Twentieth-century medicine aimed to heal the sick. Twenty-first-century medicine is increasingly aiming to upgrade the healthy. Healing the sick was an egalitarian project, because it assumed that there is a normative standard of physical and mental health that everyone can and should enjoy. If someone fell below the norm, it was the job of doctors to fix the problem and help him or her ‘be like everyone’. In contrast, upgrading the healthy is an elitist project, because it rejects the idea of a universal standard applicable to all, and seeks to give some individuals an edge over others. People want superior memories, above-average intelligence and first-class sexual abilities. If some form of upgrade becomes so cheap and common that everyone enjoys it, it will simply be considered the new baseline, which the next generation of treatments will strive to surpass.

Second, twentieth-century medicine benefited the masses because the twentieth century was the age of the masses. Twentieth-century armies needed millions of healthy soldiers, and the economy needed millions of healthy workers. Consequently, states established public health services to ensure the health and vigour of everyone. Our greatest medical achievements were the

provision of mass-hygiene facilities, the campaigns of mass vaccinations and the overcoming of mass epidemics. The Japanese elite in 1914 had a vested interest in vaccinating the poor and building hospitals and sewage systems in the slums, because if they wanted Japan to be a strong nation with a strong army and a strong economy, they needed many millions of healthy soldiers and workers.

But the age of the masses may be over, and with it the age of mass medicine. As human soldiers and workers give way to algorithms, at least some elites may conclude that there is no point in providing improved or even standard conditions of health for masses of useless poor people, and it is far more sensible to focus on upgrading a handful of superhumans beyond the norm.

Already today, the birth rate is falling in technologically advanced countries such as Japan and South Korea, where prodigious efforts are invested in the upbringing and education of fewer and fewer children – from whom more and more is expected. How could huge developing countries like India, Brazil or Nigeria hope to compete with Japan? These countries resemble a long train. The elites in the first-class carriages enjoy health care, education and income levels on a par with the most developed nations in the world. However, the hundreds of millions of ordinary citizens who crowd the third-class carriages still suffer from widespread diseases, ignorance and poverty. What would the Indian, Brazilian or Nigerian elites prefer to do in the coming century? Invest in fixing the problems of hundreds of millions of poor, or in upgrading a few million rich? Unlike in the twentieth century, when the elite had a stake in fixing the problems of the poor because they were militarily and economically vital, in the twenty-first century the most efficient (albeit ruthless) strategy may be to let go of the useless third-class carriages, and dash forward with the first class only. In order to compete with Japan, Brazil might need a handful of upgraded superhumans far more than millions of healthy ordinary workers.

How can liberal beliefs survive the appearance of superhumans with exceptional physical, emotional and intellectual abilities?

What will happen if it turns out that such superhumans have fundamentally different experiences to normal Sapiens? What if superhumans are bored by novels about the experiences of lowly Sapiens thieves, whereas run-of-the-mill humans find soap operas about superhuman love affairs unintelligible?

The great human projects of the twentieth century – overcoming famine, plague and war – aimed to safeguard a universal norm of abundance, health and peace for all people without exception. The new projects of the twenty-first century – gaining immortality, bliss and divinity – also hope to serve the whole of humankind. However, because these projects aim at surpassing rather than safeguarding the norm, they may well result in the creation of a new superhuman caste that will abandon its liberal roots and treat normal humans no better than nineteenth-century Europeans treated Africans.

If scientific discoveries and technological developments split humankind into a mass of useless humans and a small elite of upgraded superhumans, or if authority shifts altogether away from human beings into the hands of highly intelligent algorithms, then liberalism will collapse. What new religions or ideologies might fill the resulting vacuum and guide the subsequent evolution of our godlike descendants?

The new religions are unlikely to emerge from the caves of Afghanistan or from the madrasas of the Middle East. Rather, they will emerge from research laboratories. Just as socialism took over the world by promising salvation through steam and electricity, so in the coming decades new techno-religions may conquer the world by promising salvation through algorithms and genes.

Despite all the talk of radical Islam and Christian fundamentalism, the most interesting place in the world from a religious perspective is not the Islamic State or the Bible Belt, but Silicon Valley. That’s where hi-tech gurus are brewing for us brave new religions that have little to do with God, and everything to do with technology. They promise all the old prizes – happiness, peace, prosperity and even eternal life – but here on earth with the help of technology, rather than after death with the help of celestial beings.

These new techno-religions can be divided into two main types: techno-humanism and data religion. Data religion argues that humans have completed their cosmic task, and they should now pass the torch on to entirely new kinds of entities. We will discuss the dreams and nightmares of data religion in the next

chapter. This chapter is dedicated to the more conservative creed of techno-humanism, which still sees humans as the apex of creation and clings to many traditional humanist values. Techno-humanism agrees that

Homo sapiens

as we know it has run its historical course and will no longer be relevant in the future, but concludes that we should therefore use technology in order to create

Homo deus

– a much superior human model.

Homo deus

will retain some essential human features, but will also enjoy upgraded physical and mental abilities that will enable it to hold its own even against the most sophisticated non-conscious algorithms. Since intelligence is decoupling from consciousness, and since non-conscious intelligence is developing at breakneck speed, humans must actively upgrade their minds if they want to stay in the game.

Seventy thousand years ago the Cognitive Revolution transformed the Sapiens mind, thereby turning an insignificant African ape into the ruler of the world. The improved Sapiens minds suddenly had access to the vast intersubjective realm, which enabled us to create gods and corporations, to build cities and empires, to invent writing and money, and eventually to split the atom and reach the moon. As far as we know, this earth-shattering revolution resulted from a few small changes in the Sapiens DNA, and a slight rewiring of the Sapiens brain. If so, says techno-humanism, maybe a few additional changes to our genome and another rewiring of our brain will suffice for launching a second cognitive revolution. The mental renovations of the first Cognitive Revolution gave

Homo sapiens

access to the intersubjective realm and turned us into the rulers of the planet; a second cognitive revolution might give

Homo deus

access to unimaginable new realms and turn us into the lords of the galaxy.

This idea is an updated variant on the old dreams of evolutionary humanism, which already a century ago called for the creation of superhumans. However, whereas Hitler and his ilk planned to create superhumans by means of selective breeding and ethnic

cleansing, twenty-first-century techno-humanism hopes to reach the goal far more peacefully, with the help of genetic engineering, nanotechnology and brain–computer interfaces.

Gap the Mind

Techno-humanism seeks to upgrade the human mind and give us access to unknown experiences and unfamiliar states of consciousness. However, revamping the human mind is an extremely complex and dangerous undertaking. As we saw in Chapter 3, we don’t really understand the mind. We don’t know how minds emerge, or what their function is. Through trial and error we learn how to engineer mental states, but we seldom comprehend the full implications of such manipulations. Worse yet, since we are unfamiliar with the full spectrum of mental states, we don’t know what mental aims to set ourselves.

We are akin to the inhabitants of a small isolated island who have just invented the first boat, and are about to set sail without a map or even a destination. Indeed, we are in a somewhat worse condition. The inhabitants of our imaginary island at least know that they occupy just a small space within a large and mysterious sea. We fail to appreciate that we are living on a tiny island of consciousness within a giant ocean of alien mental states.

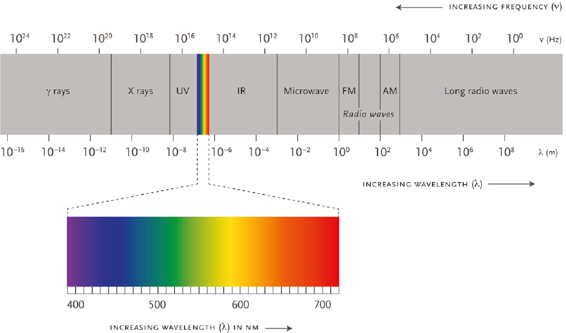

Just as the spectrums of light and sound are far larger than what we humans can see and hear, so the spectrum of mental states is far larger than what the average human is aware of. We can see light in wavelengths of between 400 and 700 nanometres only. Above this small principality of human vision extend the unseen but vast realms of infrared, microwaves and radio waves, and below it lie the dark kingdoms of ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. Similarly, the spectrum of possible mental states may be infinite, but science has studied only two tiny sections of it: the sub-normative and the WEIRD.

For more than a century psychologists and biologists have conducted extensive research on people suffering from various

psychiatric disorders and mental diseases. Consequently, today we have a very detailed (though far from perfect) map of the sub-normative mental spectrum. Simultaneously, scientists have studied the mental states of people considered to be healthy and normative. However, most scientific research about the human mind and the human experience has been conducted on people from

W

estern,

e

ducated,

i

ndustrialised,

r

ich and

d

emocratic (WEIRD) societies, who do not constitute a representative sample of humanity. The study of the human mind has so far assumed that

Homo sapiens

is Homer Simpson.

In a groundbreaking 2010 study, Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan systematically surveyed all the papers published between 2003 and 2007 in leading scientific journals belonging to six different subfields of psychology. The study found that though the papers often make broad claims about the human mind, most of them base their findings on exclusively WEIRD samples. For example, in papers published in the

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

– arguably the most important journal in the subfield of social psychology – 96 per cent of the sampled individuals were WEIRD, and 68 per cent were Americans. Moreover, 67 per cent of American subjects and 80 per cent of non-American subjects were psychology students! In other words, more than two-thirds of the individuals sampled for papers published in this prestigious journal were psychology students in Western universities. Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan half-jokingly suggested that the journal change its name to the

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology of American Psychology Students

.

1

Humans can see only a minuscule part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The spectrum in its entirety is about 10 trillion times larger than that of visible light. Might the mental spectrum be equally vast?

‘EM spectrum’. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EM_spectrum.svg#/media/File:EM_spectrum.svg.

Psychology students star in many of the studies because their professors oblige them to take part in experiments. If I am a psychology professor at Harvard it is much easier for me to conduct experiments on my own students than on the residents of a crime-ridden New York slum – not to mention travelling to Namibia and conducting experiments on hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari Desert. However, it may well be that New York slum-dwellers and Kalahari hunter-gatherers experience mental states which we will never discover by forcing Harvard psychology students to answer long questionnaires or stick their heads into fMRI scanners.