How to Create the Next Facebook: Seeing Your Startup Through, From Idea to IPO (22 page)

Read How to Create the Next Facebook: Seeing Your Startup Through, From Idea to IPO Online

Authors: Tom Taulli

Get the buyer to pay for everything, including legal fees and the investment banking fees, whether the deal goes through or not.

In rare cases, you may also get a

breakup fee

: a set amount that goes to the seller if the buyer terminates the deal. To help avoid this, the buyer will negotiate a

material adverse change clause

. This means the buyer can back out of the deal if there is a major deterioration in the business.

A breakup fee often ranges from 2% to 10% of the value of the deal. However, such arrangements are mostly for large deals, such as Instagram (the breakup fee was $200 million). These complex transactions can take six months to a year to complete; and there’s always a possibility that antitrust authorities will block the deal. A breakup fee can compensate for the risks.

For tech deals, the buyer generally puts together employment agreements for key employees. When negotiating these documents, you should retain your own counsel; the corporate counsel looks out for the company’s interests—not yours.

A major part of the negotiation is about compensation, so work hard to get a lucrative salary and equity package! But there are other critical areas to negotiate as well:

It’s common for founders to be fired. They’re going from being leaders to being employees, and it’s a tough transition.

In the employment agreement, the buyer generally says it has the right to terminate employees for “cause.” This statement seems innocuous, but it’s fairly broad. You should limit it to areas like criminal activity, fraud, gross dishonesty, and consistent failure to discharge one’s duties.

Even better, you should negotiate a requirement that there be “good reason” for termination. This makes the burden even tougher for the employer. Examples include materially changing compensation, depriving you of your title, or forcing you to relocate.

If you are terminated without cause, or there is no good reason, then you’re entitled to some type of severance payment. This may include one to two years’ worth of salary as well as full vesting of any options.

The severance payment may also be considered a

golden parachute

(if it’s 2.99 times the average taxable income over the past five years). In this situation, you’ll owe a 20% excise federal tax. Because of this, try to negotiate for a

gross up

, which effectively means the employer pays for the liability.

You should also ensure that there is no mitigation or offset clause. If not, then you may be required to give back part of your severance when you find a new gig.

If the buyer’s company is also purchased, you should get full vesting of your options. In this scenario, there is a high risk that you will be terminated.

If your firm is purchased by a public company, you may be considered an insider. This means you could be exposed to shareholder litigation. So, in the employment agreement, make sure the employer will cover you under the directors’ and officers’ policy and provide indemnification.

Unless you are a rock-star employee, you need to accept this clause. The employer generally requires that—when you leave the company—you won’t work for a rival or build a new company in the same space. The agreement should have a time limit, say one to two years. You also should try to narrow the industry focus in the clause.

Courts usually look unfavorably on noncompete agreements. The prevailing belief is that employees should have the right to work where they want.

But there is an exception: acquisitions. After all, part of the purchase price is exclusive use of the services of key employees. In other words, the noncompete agreements will likely be enforceable.

Selling your company can be stressful. Are you selling too soon? Might you be leaving lots of money on the table? Can you work as an employee with the new company? Before making a decision, you must think about your goals. You also need to negotiate hard, because there will be no way to undo the transaction.

The next chapter looks at another type of exit: an IPO. It can be a thrilling experience and create lots of wealth, but it has its own risks.

You made a commitment to [our employees and investors] when you gave them equity that you’d work hard to make it worth a lot and make it liquid, and this IPO is fulfilling our commitment. As you become a public company, you’re making a similar commitment to our new investors and you work just as hard to fulfill it.

—Mark Zuckerberg’s letter to shareholders, February 2012

Ahead of the Facebook IPO on May 18, 2012, just about everyone around the world thought it would be a huge success. It seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a killing. There were stories of people preparing to put their life savings into the stock.

To meet the demand, Facebook boosted the number of shares offered by 100 million and hiked the price range from $28–$35 to $34–$38. One report indicated that the offering was oversubscribed by 20X in Asia alone.

But on the day of the IPO, nothing seemed to go right. NASDAQ’s computer system went haywire due to the influx of orders, and it took hours for investors to get confirmations. The stock went from $42 to $38.

But this wasn’t the end of the deterioration. Within a few months, the stock dropped to $23, and investors lost $39 billion. The IPO dream turned into a nightmare.

The full story of the offering may never be known. But it offers some important lessons, which this chapter examines. Before doing this, let’s cover the fundamentals of IPOs.

An IPO is when a company first issues stock to the public, usually through a national exchange like the NYSE or NASDAQ. There are many reasons to do this, but the primary one is to raise capital. Often, all the money goes to fund a company’s growth. With larger companies, part of the proceeds may also go to buy the shares of insiders, including venture capitalists and employees.

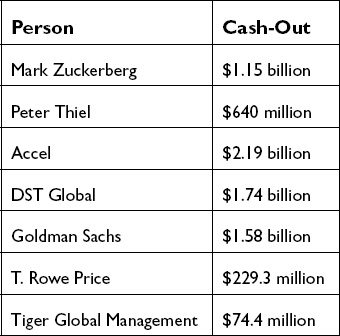

Facebook raised $16 billion from its IPO, making it the second largest offering in US history. About 43% of the capital went to the company and the remainder to insiders. Here’s a rundown:

Another important reason for an IPO is to gain credibility. A company must undergo rigorous auditing and compliance requirements first, so potential customers and partners have much more confidence in doing business with the company.

Being public also means a company can easily use its stock as currency to buy other companies. It has a discernible value and is liquid because it’s traded every business day. The company also benefits from cash savings.

Once a company is public, it often becomes easier to raise additional capital. A group of investors understands the company’s story and may be willing to buy more shares. It also helps that the company has been periodically publishing its financials.

When a company offers shares after an IPO, the financing is called a

secondary offering

. For the most part, a company does this when the valuation is fairly robust.

Facebook waited about eight years to go public. For a company of its scale, this was definitely a long time. Google, on the other hand, waited only about five years.

Zuckerberg made it clear that he wanted to wait as long as possible before becoming a public company. The primary reason he pulled the trigger on an IPO was an archaic federal securities rule, which said that once a company reaches 500 shareholders, it must begin making public disclosures through the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The irony is that the rule was changed after Facebook began the IPO process; the new limit is now 2,000 shareholders.

Why did Zuckerberg have such an aversion to going public? One key motivation was his desire to keep private the company’s plans and financials, which helped to give Facebook a competitive edge.

But perhaps the most important reason was that Zuckerberg didn’t want the distractions of dealing with public shareholders, Wall Street analysts, and the onerous regulatory requirements. Most Wall Street investors—except a few like Warren Buffett—want to see short-term results and will dump a stock if it doesn’t meet lofty expectations. When Facebook reported its first quarterly report, Zuckerberg got a striking example of this behavior: the stock plunged 12%. But he didn’t let it change his long-term approach, which he emphasized on Facebook’s first earnings conference call as a public company.

Because of the plunge in the stock price, Zuckerberg got first-hand experience with yet another negative aspect of IPOs: shareholder lawsuits. It didn’t take long for lawyers to put together complaints and make him the defendant. Although Facebook has sufficient insurance and legal resources to fight the lawsuits, they are still a major distraction for the company.

A stock plunge can even encourage hostile takeovers, but Zuckerberg wisely implemented a structure to minimize this possibility. He created two types of stock: Class A and Class B. The Class B stock gave him 10 votes per share, and the Class A stock had only one vote. This meant Zuckerberg maintained nearly 56% of the voting power after the IPO, which would make it incredibly difficult for an outside shareholder to gain control. The dual-class structure has been popular with other major social media operators like Zynga, LinkedIn, and Groupon.

An IPO also means a company is saddled with ongoing costs that can easily range from $3 million to $5 million a year. These expenses are for lawyers, auditors, and investor relations firms. They are critical for putting together

the financial disclosures and implementing the core systems to make sure the company is in compliance with the myriad laws and regulations.

At the core of all this is the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) law. Congress passed the landmark legislation in 2002 in response to the accounting scandals at Enron and WorldCom. The goal was to make corporate fraud a thing of the past.

It was certainly a good idea and helped to bring back confidence in the markets. But the requirements proved to be fairly onerous. For example, a company’s CEO and CFO must sign the quarterly and annual reports. If these disclosures wind up being fraudulent, these executives may face fines of up to $5 million and prison terms of 20 years.

But perhaps the toughest requirement is Section 404, which requires that an auditor test a company’s internal controls and financial system. This can be a time-consuming and expensive process.

SOX certainly helped to reduce corporate fraud, but it also meant far fewer IPOs. This definitely isn’t a good thing, because a healthy financial market is critical for encouraging the creation of new ventures. Investors have a bigger incentive to put money to work if IPOs are a likely option.

In 2012, President Obama and Congress passed legislation to pare back SOX with the passage of the JOBS Act. It reduces some of the disclosure requirements and eliminates the need for Section 404 if a company fits the definition of an

emerging growth

company (has less than $1 billion in annual revenues). It’s too early to tell what the impact of the JOBS Act will be. But by lessening some of the burdens from SOX, it should have a positive impact and allow for a more robust IPO market.

An IPO can take from 6 to 12 months. In addition, much preparation is required to get the company

IPO ready

, which involves implementing a strong financial reporting system and hiring key senior executives. Such efforts can easily take a year or more.

In the case of Facebook, a key hire was Sheryl Sandberg, who became the company’s chief operating officer. Facebook also filled the critical role of the chief financial officer (CFO): this spot went to David A. Ebersman, who came on board in September 2009. Before this, he was the CFO of Genentech, a major biotech company. He also had Wall Street experience as a stock analyst at Oppenheimer & Co.

Besides a strong senior management team, a company also needs to retain top-notch advisors. The main ones are described next.

An underwriter is a Wall Street firm that manages the IPO process. Responsibilities include drafting the prospectus, coming up with a valuation, and locating the right investors.

An underwriter is generally compensated based on the amount raised, ranging from 2% to 7%. But Facebook’s underwriter, Morgan Stanley, received only 1%, primarily because all the top underwriters worked aggressively to get the assignment due to its high profile.

Many attorneys are involved in an IPO. They help with the complex legal issues inherent in state and federal securities laws.

It’s important to retain a firm that has significant experience with the process and also knows how to deal with the SEC. You may even need to hire overseas law firms, if the IPO has substantial interest from foreign investors. For example, Facebook issued large numbers of IPO shares to investors in Europe as well as Japan and Singapore.

This is a firm that vouches for a company’s financial statements. For an IPO, the auditor must be registered with the SEC.

The auditor performs a variety of duties, the most important of which is to issue a

comfort letter

. It provides assurance that the financial statements are in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

In some cases, an auditor issues a

going concern

statement. This means it believes the company may be vulnerable to going bankrupt!

To get ready for an IPO, a company needs to do more than just get its books in order and hire top people. It also needs a highly disciplined approach to product development.

Zuckerberg has had to go through this evolution. In the early days, he provided no warnings about any changes to the Facebook platform—he just released the product or feature. This was jarring for users, and often, many complained. Zuckerberg considered it a positive sign because there was lots of passion about the product.

But as an organization grows, the seat-of-the-pants approach can be fatal. Zuckerberg has made some major changes in his strategy, which has become much more methodical. This was evident in the development of the Timeline. The project’s origins go back to brainstorming sessions with Sam Lessin, a Harvard pal of Zuckerberg who came on board Facebook through the October 2010 acquisition of Drop.io.

Once he had some clear ideas, Zuckerberg set in motion a careful project plan that lasted 18 months. It involved the kinds of things you would have at any big company, such as focus groups and many iterations (there were more than 100 different versions of the Timeline).

To test the Timeline, Facebook first launched it on an experimental basis in New Zealand. This was an effective way to get valuable feedback and tweak the product. At the same time, Facebook began educating advertisers and development partners; they needed to be ready to make for a smooth transition.

This kind of discipline can be a hindrance to an early-stage company. But as time goes by, a transition is necessary. It can be tough and full of mistakes, but it’s essential in order to scale growth.

When a company decides to go public, it must first select a lead underwriter. The process is called a

bake-off

, and it involves numerous presentations. A company may hire two or more lead underwriters (called

co-underwriters

or

co-managers

); sometimes this is about showing more credibility. For tech companies, it’s common to have Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs as co-managers.

Of course, a company wants other benefits in addition to brand value. For example, it’s smart to see if an underwriter has strong retail investor bases, respected analysts, and an extensive trading organization. Post-IPO services are also important. A top underwriter provides advice on matters like mergers and secondary offerings.

Once a company selects an underwriter or co-underwriters, there is an all-hands meeting. This sets forth the main goals and timetable.

The first deliverable is the

prospectus

, also known as the

S-1

. It includes the financials, risk factors, executive compensation, financing history, and business plan. Until the S-1 is filed with the SEC, the company is not allowed to make any announcements about its intention to go public. Violating this rule is called

gun jumping

and can mean delaying the IPO.