How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare (44 page)

Read How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Online

Authors: Ken Ludwig

Tags: #Education, #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Arts & Humanities, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #General

Most theater professionals would agree that nothing better has ever been written about the profession of acting. If any of your children loves acting, have him learn every word of it. I learned it when I was about twelve, and my children learned it early as well. It will always, always be of value to anyone who loves the theater.

Reluctantly, we end our study of

Hamlet

at this point. Hundreds of books the size of this one have been written about

Hamlet

alone, and yet the nuances and meaning of the play have never been exhausted and never will be. It speaks to each new generation in a different way and casts its shadows differently with each century. Your children will always be wiser and better for knowing

Hamlet

. And with its vast intelligence, it serves as the perfect prelude to the final play we’ll be studying together,

The Tempest

.

Passage 25

A Summation

Our revels now are ended. These our actors

,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision

,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces

,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself

,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve;

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded

,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep

.

(

The Tempest

, Act IV, Scene 1, lines 165–75)

T

he Tempest

is the last play wholly written by Shakespeare, and it is fair to think of it as his final, valedictory statement to his audience. It is also a mysterious play, mysterious in the manner of other great works of art by geniuses in their final maturity. The late novels of Henry James are mysterious in this way, as are the final string quartets of Beethoven and the final cutouts of Matisse. These works represent both a summing-up and a breakthrough: a new approach to presenting ideas that have become deeper and richer over a lifetime. Such works of art are often expressed in new forms and with new insights, building on the artistic complexity that has been growing within the artist over the years,

yet with moments of simple clarity that make us pause with wonder. This doesn’t mean that we have to like these later works more than their youthful counterparts, or that they’re “better” or more artful. However, your children should gain an understanding of how late works like

The Tempest

contain sounds and images that somehow cross into new territory for the artist.

One of the comforts we can all share in our study of Shakespeare is the knowledge that as an artist Shakespeare completed the work that he was meant to do. He was not cut off in his prime like Mozart or Van Gogh, both of whom died in their thirties. Shakespeare finished

The Tempest

around 1611, at the age of forty-seven, and soon after that he retired to his hometown of Stratford, where he died in 1616. In his final years he collaborated on some minor works, but by the time he died, he had completed his life’s work.

The Tempest

is a spiritual play and an odd play. It draws on folklore, mythology, and magic, and it contains themes and situations from his earlier comedies. It also draws on reports of the discovery by European explorers of primitive, unsettled lands across the ocean that had filtered back to Elizabethan England. It is one of Shakespeare’s four last plays, which include

Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale

, and

The Tempest

. These four are similar enough in tone to warrant their own grouping in most modern editions, where they are usually called The Romances. The critic Barbara Mowat has emphasized the innovative nature of these works, in each of which Shakespeare combines tragedy, comedy, and romance, and she has suggested that they are best described as “dramatic romances.”

I want your children to memorize the passage above because I believe it can be considered Shakespeare’s personal statement of farewell to his art. This view may sound romantic on my part, and there are skeptics; but I’m joined by many scholars in believing that not only this speech but the play as a whole represents Shakespeare’s valedictory to playgoers for all posterity.

Our revels now are ended

.

The speech is spoken by a man named Prospero, who was once the Duke of Milan but was exiled twelve years ago, his title usurped by his

ambitious brother. Prospero was cruelly set adrift on the ocean with his three-year-old daughter, Miranda; however, a wise old friend secretly smuggled supplies—as well as books on magic—aboard the rotting boat, and eventually Prospero and Miranda reached a remote island, which is where the play takes place.

By the time the play begins, Prospero has developed into a great wizard. Since arriving on the island, he has learned to control the elements, he has released a fairy sprite (now his servant) named Ariel from the prison of a witch named Sycorax, and he has enslaved the witch’s son, a brutish monster named Caliban, whom he had once hoped to civilize.

When the play opens, Prospero has conjured up a storm around his island in order to wreck a ship carrying his villainous brother. Prospero’s plan is to have his brother and his evil friends wash ashore on his island, where he can keep track of them and control them. He may have revenge

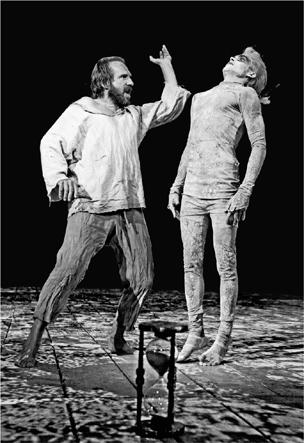

in mind—we’re never quite sure; but as the play progresses, we see Prospero come to terms with his past and gain a spirit of forgiveness, regardless of the unforgivable nature of the injuries that were done to him. His change of heart results from a mysterious moral journey that comprises a series of incidents, including

The Tempest

at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, with Ralph Fiennes as Prospero and Tom Byam Shaw as Ariel

(photo credit 40.1)

• Ariel’s desire to gain his freedom;

• the treatment that the lowly Caliban receives at Prospero’s own hand;

• the philosophy espoused by the kind courtier who placed provisions on Prospero’s raft those many years ago; and

• the benevolence Prospero feels when witnessing his daughter Miranda falling in love with one of the survivors

.

Indeed, Prospero’s spirit of forgiveness in the face of past injury seems to be the central theme of the play.

The Play-Within-the-Play

Like

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

and

Hamlet, The Tempest

involves a play-within-a-play, only here it is more subtle. The outer play, or “real” events, concern Prospero as a sort of god—or playwright, if you will—who manipulates the lives of the shipwrecked visitors so that their stories become a kind of inner play-within-the-Prospero-play. Prospero’s stage manager is Ariel, the fairy sprite he has released from prison who hopes that by doing Prospero’s bidding this one last time he will gain his freedom for eternity.

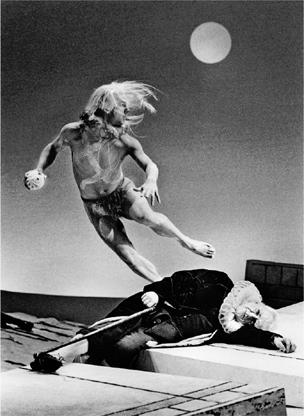

The inner play is made up of three related stories that play out as Prospero manipulates the scenario from above: (1) the story of evil courtiers who plot to kill the current Duke of Milan and usurp the throne; (2) the parallel story of two clownish servants who join with the monster Caliban in a plan to kill Prospero himself; and (3) the story of the courtship of Miranda and Ferdinand, the prince of Naples. Explain to your children that one of the joys of the play is Miranda’s innocence: When the play opens,

the fifteen-year-old girl has never seen a fellow human being before except her father. She is amazed when she first sees Ferdinand, and she instantly falls in love with him. Then, near the end of the play, when she sees the other shipwrecked humans gathered together for the first time, she cries:

The Tempest

at the American Repertory Theater, with Vera Zorina as Ariel

(photo credit 40.2)

O brave new world

,

That has such people in it!

Ironically, Miranda is standing on an island that will become the brave new world of the seventeenth century. European exploration will reach its height in the decades after this play is written. But Shakespeare seems to have an additional world in mind: He seems to be implying that human beings, not islands in the sea, will always be the “brave new world” that requires perpetual rediscovery if the human race is ever to grow in spirit.

The Masque

The specific circumstances of the speech we’re memorizing have to do with the performance of a masque. A masque is an entertainment that was popular among nobility in the seventeenth century, where actors, dancers, and often nobles performed poetic scenes to the accompaniment of music, often wearing masks. About halfway through

The Tempest

, Prospero gives Miranda permission to marry Ferdinand, and in celebration he has Ariel and other spirits under his control perform a masque for the lovers. During the masque, something reminds Prospero of Caliban’s treachery, and angrily he halts the festivities and makes the spirits vanish. Ferdinand looks frightened, and Prospero says to him:

PROSPERO

You do look, my son, in a moved sort [disturbed manner],

As if you were dismayed. Be cheerful sir

.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors

,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

Indeed, the actors

were

all spirits and included the goddesses Iris, Ceres, and Juno. And when Prospero halted the revels, they

melted into thin air

like magic. As Hamlet said with regard to the Ghost,

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy

.

Review the first three lines with your children one more time:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors

,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And now add:

And like the baseless fabric of this vision

[spectacle],

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces

,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself

,

Yea, all which it inherit

[inhabit],

shall dissolve;