If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (4 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

The ‘ten-second bed’, put to rights with the flick of a wrist, also made a proud appearance in Habitat catalogues. The fabrics pictured were boldly coloured or patterned, as far distant from the pristine white of Victorian bed linen as possible. Modern and striking, they were navy, magenta, mustard, striped or flowered. People experimented by buying duvets for their children first, and those born in the 1970s – myself included – grew up knowing nothing else (though I remember overhearing the reservations of my grandmother and her friends: ‘Isn’t it heavy? Isn’t it hot?’).

But few people, once they’d tried duvets, went back to sheets and blankets. In fact, anyone still found sleeping under many layers of bedding is actually indulging in conspicuous

consumption: they, or their staff, have the time to put such a bed back together in the morning, and to clean the component sheets, blankets, eiderdowns and throws according to their various complicated requirements.

The simplicity of most modern beds – just one mattress, just one covering – takes us back in a strange kind of circle to the medieval period, when a sack full of straw and a cloak were all one needed.

2 – Being Born

Grant we beseech thee to all infants yet unborn, that knit together with their due veins and members, they may come forth into this world sound and perfect without fault or deformity.

Thomas Bentley, a prayer for pregnant women, 1582

Until lying-in hospitals began to appear in the eighteenth century, nearly everyone was born at home. Life began in a bedchamber, and more often than not it ended there too, perhaps in the very same family bed. Until these great events were shuffled off to hospitals, this room was the first and last sight a person saw.

Any expectant mother today feels some sense of trepidation, but in the past the stakes were much higher. Childbirth was the biggest risk to life for young women, and the bedchambers to which they retired as their time drew near were frightening, daunting places. The medieval death rate was one in every fifty pregnancies. Considering that it wasn’t unusual for a woman to give birth a dozen times, the odds quickly mounted up for reproductive wives. Many pregnant Tudor ladies had their portraits painted for the poignant reason that they might well have been saying goodbye to their husbands for ever when they disappeared into confinement. If so, their families would

at least have had a final image of a lost loved one (

plate 8

).

The Tudors knew what proponents of natural birth still know today: gravity helps. Sixteenth-century queens sat in a seat-less throne called the ‘groaning chair’, upholstered in gold cloth and complete with a copper bowl to catch the afterbirth. Cruder, seat-less stools were in the possession of midwives serving all ranks of society. Some had fancier features such as leather seats, ratcheted backs or handles for the woman to grip as she pushed.

The final few weeks of their pregnancies were filled with elaborate rituals for Tudor and Stuart women of high status. A well-prepared woman would have entered her marriage already equipped with her set of ‘childbed linen’, of both ceremonial as well as practical purpose. Now the various cloths and sheets lovingly prepared and stored in a chest would be brought out for use. The effort spent upon their preparation showed that a woman was ready to become a mother both physically and psychologically.

During the later stages of her pregnancy, a Tudor or Stuart woman would literally withdraw from the world. Sixteenth-century households sealed their pregnant women into darkened, well-furnished rooms for a whole month before the birth to minimise the risks of a miscarriage-inducing fall or fright. The darkness and stuffiness was to reduce the entry of bad ‘airs’, which, according to contemporary medicine, carried disease.

This theory that an evil ‘miasma’ carried illness through the ether was terribly important in the history of house-planning, and we will hear much more about it. It also caused great attention to be paid to the aspect of a house; a dangerously damp or valley site would have bad air, and therefore disease. You can understand why people thought like this. Malaria, for example, was common in the swamps of Tudor England. But it was spread by mosquitoes, not an imaginary ‘miasma’.

Even after the great event, the new Tudor mother was not allowed to escape from her birthing chamber. She would be revived there with ‘caudle’, a sort of alcoholic porridge. Only

two weeks later was she washed, her soiled straw mattress changed and she herself allowed to sit up. The ‘upsitting’ and the ‘footing’ a fortnight later when she got out of bed were celebrated by the women of the household with all-female parties. These rituals were taken over to New England as well: Mary Holyoke of Salem’s eighteenth-century diary records how she ‘kept chamber’ before being ‘brought to bed’, hosting a party for five female friends two weeks later.

Being locked up for a period of enforced rest after giving birth may sound rather horrible, but it took women through the really dangerous days during which so many of them died from loss of blood or from puerperal fever (septicaemia; basically caused by dirty hands, and incurable). Lying-in continued until the conclusive ceremony of ‘churching’ a month after the birth, when the woman left the house to return to church (and came home to return to her husband’s bed).

The gathering of the women, the gossiping, the pleasure they took in their shared experience made giving birth a much more sociable event than it is today, when it’s chiefly an individual drama. In fact, the bonding nature of childbirth explains why the users of the ‘molly-houses’ (male brothels) of early eighteenth-century London replicated its rituals: homosexual men pretended to give birth, and celebrated with the traditional party afterwards. The first known piece of printed gay porn was entitled

A Lying-In Conversation with a Curious Adventure

(1748), and it describes a man in drag infiltrating a lying-in chamber. Fetishising childbirth is not common in modern male gay society, and that’s probably because lying in bed alone in a hospital is not nearly so much fun.

Babies made their first appearance amid a world of women, with males being kept out of the birthing chamber until deep into the eighteenth century. ‘My wife’s mother came to me with tears in her eyes,’ wrote Nicholas Gilman in 1740. ‘O, says she, I don’t know how it will fare with your poor wife, hinting withal

her extreme danger.’ Mr Gilman was entirely in the hands of his mother-in-law for information about the life or death of his spouse, and childbirth was the one part of household life over which men had no control.

Even expectant husbands paid due respect to the wise women called in to advise upon such occasions. Midwives were figures of enormous and mysterious power, well able to diagnose difficulties through years of practical experience. Because of the hold they held over the emotions of hopeful parents, they were able to use ‘magic’ to predict and to protect in a manner at which science would scoff. For aristocrats, the gender of the baby was of huge significance, and a male heir for the estates was always desperately sought after. A seventeenth-century midwife would try to win a bigger fee by predicting a boy rather than a girl. Clues would be provided by the condition of the mother’s breasts: ‘ye Nipple red, rising like a strawberry’ was a good sign.

While childbirth was often a communal experience, sometimes harrowing, sometimes joyful, there could be other people present in the birthing room for reasons of surveillance rather than support. For example, events that took place in the bedchamber of Mary of Modena, the wife of the unpopular King James II, led to a revolution. James II had long been annoying his subjects with his despotic and Catholic policies, and when his young Italian wife gave birth in 1688 to a healthy baby boy, the king’s enemies were chagrined that his position had been so strengthened. To discredit him, they put it about that Mary’s baby had in fact died and that an imposter had instead been smuggled into her bed in a warming pan.

The rumour grew into a long-lasting and damaging smear against James II, and the baby would never be king. James II was overthrown soon afterwards, and his son grew up to be the ‘Pretender’, a rival, Catholic and unsuccessful bidder for the throne now seized instead by James II’s firmly Protestant daughters.

There are two reasons for mistrusting the story of the warming pan, which is said to have taken place in the velvet bed now standing in the Queen’s Bedchamber at Kensington Palace (

plate 5

). Firstly, a warming pan itself, a kind of frying pan containing hot coals to warm cold sheets, is hardly big enough to hold a baby. Secondly, to avoid any such monkey business a royal confinement was attended by many members of the court and church acting as witnesses. Mary of Modena gave birth with at least fifty-one other people present, plus ‘pages of the backstairs and priests’, and it seems unlikely that such a large number could have maintained a conspiracy with success.

This concern about the birth of a true heir to the British monarchy persisted into the twentieth century. When the Queen Mother gave birth to our current queen in 1926, the Home Secretary came to the house to wait and watch (though he wasn’t actually in the room itself). This undignified custom was only suspended by George VI, who thought it ‘archaic’.

At lower levels in society, the midwife could spill the secrets of her clients, and feminine betrayal took place in some bedchambers. A midwife could detect a woman’s adultery, infanticide or pre-marital sex. A ‘monstrous’ birth or malformed foetus would suggest that immoral behaviour had taken place: the seventeenth-century governor of New England, Sir Henry Vane, for example, had two women servants in his household; ‘he debauched both, & both were delivered of monsters’.

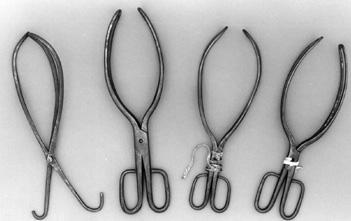

During the course of the seventeenth century, men finally began to penetrate the birthing chamber and its mysteries. They brought with them a healthy dose of scepticism about many of the ancient customs surrounding childbirth, and they also introduced a new and important piece of birthing-chamber equipment: the forceps. These iron tongs were invented around 1600 by one Peter Chamberlen, but he kept them as a family secret, thereby building up an extremely impressive reputation for the dynasty of doctors that he founded. But it’s William Smellie of

Scotland (1697–1763) who’s usually given credit for bringing the forceps into wider use.

The forceps which revolutionised childbirth: the original set belonging to the Chamberlen family

There’s no doubt that using them saved many lives. Previously, an iron hook had been used to drag out babies reluctant to emerge, which inevitably killed them. Yet midwives had misgivings about the forceps.

The Ladies Dispensatory, or Every Women Her Own Physician

(1739) recommended they be employed only in extreme circumstances, defined as cases where labour had lasted for

four or five

days.

The male physician began steadily to usurp the midwife’s ground, even if he had much less practical experience, and gradually took control over childbirth away from women. A minister named Hugh Adams, of Durham, New Hampshire, claimed to have sorted out a very difficult confinement in 1724. He was called in after a midwife had despaired of a three-and-a-half-day labour, even though he had never delivered a child before. He performed his miracle only with some ‘strong Hysterick medicines’ and the knowledge he had gleaned from reading a few books.

Circumstances like these caused ‘Old Wives’ Tales’ to begin to take on their modern reputation for inaccuracy and fallibility. Yet the male midwife would remain a figure of much suspicion throughout the Georgian period. The idea that another man would see his wife’s private parts was troubling to many husbands. In satirical caricatures, the male midwife was often depicted with his ranks of medicine bottles, many of them containing sedatives which he used to knock out women in order to have his wicked way with them (

plate 9

).