If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (2 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

The functions of bedroom and living room eventually became separate, yet the bedroom remained a social space for a surprisingly long time. Guests were received in bedrooms as a mark of favour, courtship and marriage were played out here, and even childbirth was for centuries a communal experience. Only in the nineteenth century did the bedroom become secluded, set aside for sleep, sex, birth and death. In the twentieth century, even the last two left the bedroom behind and went off to the hospital.

Because the room in which you slept was so much more than just a place of rest, the history of the bedroom is a vital strand in the history of society itself.

1 – A History of the Bed

There are few nicer things than sitting up in bed, drinking strong tea, and reading.

Alan Clark, 27 January 1977

Once upon a time, life’s great questions were: would you be warm tonight and would you get something to eat? Under these circumstances, the central great hall of a medieval house was a wonderful place to be: safe, even if smoky, stinking and crowded. Perhaps its floor was made only of earth, but no one cared if the hall was full of company, warmth and food. Many people, then, were glad to doss down here. At night the medieval great hall became a bedroom.

A medieval great household was rather like a boarding school in which most of the pupils were grown up. They came from humble homes to live and learn at a centre of culture and security for the surrounding area. They served their lord by day, and slept on his floor by night. If you had a particular job in the household, you perhaps slept in your daytime place of work: we hear of laundry-maids sleeping in the laundry, porters sleeping in their lodges, and kitchen staff bedding down near the fireplaces where they worked all day. A Tudor inventory made at Sutton Place in Surrey shows that the ‘lads’ of the kitchen slept in the same room as the household’s fool. The one place you didn’t sleep was a bedroom.

So nearly everyone shared their sleeping space with numerous other people. You’ll often read that medieval people had no notion of privacy. Certainly it should not be assumed that it exists in every culture. In modern Japan, for example, privacy is much less important than in the West. Lacking their own word for the concept, the Japanese have adopted an English one, ‘

praibashii

’.

Medieval lives were much more communal than those of today, but that’s not to say that they contained no notion of privacy at all. People still took the trouble to seek out private moments, such as the times when lord and lady lay curtained off in their four-poster bed, or when a courting couple walked out into the woods in merry Maytime, or when a person knelt in prayer in an oratory. The private book, the locked and private box containing personal treasures, or the private oratory were private places indeed, even if smaller or less accessible than a modern person might expect.

On the other hand, there was, indeed, less ‘private life’. Society was structured so that one’s position in the hierarchy was obvious and explicit. There was a ‘Great Chain of Being’ extending down from God, through his angels, to the Archbishop of Canterbury and other notables such as dukes, before normal people got a look-in. But at least we lesser mortals could take comfort from being placed above the animals, the plants, and finally, the stones. Such a chain inevitably restricted people’s hopes of bettering their social position, but it also comforted them. Those higher up adopted airs of superiority, but they also had clear and pressing responsibilities towards those lower down.

In this communal but strictly hierarchical world, literacy was rare; so, therefore, was diary-writing and introspection; so was time free from getting and making food. God, not the self, was the centre of the world. Understanding what it might have been like to inhabit such a mental world is the ultimate aim of

historians’ efforts in researching and constructing medieval furniture and the rooms it stood in.

Medieval beds for most people consisted of hay or straw (‘hitting the hay’ had a literal meaning) stuffed into a sack. These sacks might be made out of ‘ticking’, the rough striped cloth still used to cover mattresses today. A mattress might also be known as a ‘palliasse’, from ‘

paille

’, the French word for straw. John Russell in

c

.1452 gives instructions for making a bed for several sleepers, 9 ft long by 7 ft wide. He says you should collect ‘litter’ (presumably leaves, not crisp packets) to ‘stuff’ the mattress. Then the stuffing should be distributed evenly to remove the worst lumps. Each simple mattress should be ‘craftily trod … with wisps drawn out at feet and side’.

It sounds rather uncomfortable, but presumably it was softer than the floor.

And snuggling up together in a big bed was normal, indeed desirable, for warmth and security. A French phrase book for use by medieval travellers included the following useful expressions: ‘you are an ill bed-fellow’, ‘you pull all the bed clothes’ and ‘you do nothing but kick about’. The sixteenth-century poet Andrew Barclay describes the horrible sounds that could be expected in a roomful of sleepers:

Some buck and some babble, some cometh drunk to bed,

Some brawl and some jangle, when they be beastly fed;

Some laugh and some cry, each man will have his will,

Some spew and some piss, not one of them is still.

Never be they still till middle of the night,

And then some brawleth, and for their beds fight.

Because it was so easy to annoy or inconvenience your bedfellows, custom and etiquette developed about how to take your position in a communal bed. An observer of life in early-nineteenth-century rural Ireland noted that families lay down ‘in order, the eldest daughter next the wall farthest from the door, then all the sisters according to their ages, next the mother,

father and sons in succession, then the strangers, whether the travelling pedlar or tailor or beggar’. Thus the unmarried girls were wisely kept as far as possible from the unmarried men, while husband and wife lay together in the middle.

William Harrison’s is the best-known description of servants’ beds in the Elizabethan age: ‘if they had any sheets above them, it was well, for seldom had they any under their bodies, to keep them from the pricking straws that ran oft through the canvas’. Yet his comments must be taken with a pinch of salt because Harrison actually thought that a bit of discomfort was good for you. Like conservative commentators in all periods, he was bemoaning the fact that Englishmen had turned into softies, wanting all kinds of unmanly luxuries. Pillows, he said, were formerly ‘thought meet only for women in childbed’; how times had changed when even

men

wanted pillows, instead of making do with ‘a good round log under their heads’.

But sleeping in the great hall wasn’t good enough for the actual blood family who owned the medieval manor house. The lord and lady might retire from the company of hoi polloi into an upstairs room adjoining the hall. Often it was called simply ‘the chamber’, sometimes the ‘bower’ or ‘solar’. (The ‘chamber’ was overseen by a special servant called the ‘chamberlain’.) In the chamber at Penshurst Place in Kent, one of Britain’s most complete surviving medieval houses, a peephole or squint gives a view down into the hall below so that the boss could see what his employees were getting up to. He literally ‘looked down’ upon his servants.

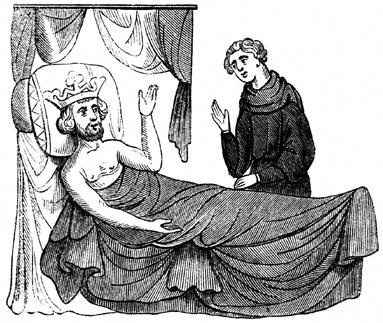

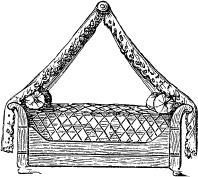

The lord and lady’s chamber was a multifunctional place: home office, library, living room and bedroom combined. But it almost certainly contained a proper wooden bed. It’s quite hard to work out exactly what these beds looked like because medieval artists usually ran into difficulties with the proportion or the scale. When we made a reconstruction of Edward I’s bed for the Medieval Palace at the Tower of London, our evidence included

documents recording payment for its green posts painted with stars, and for chains to link the various parts together (

plate 2

). The contemporary illustration showing ‘The Conception of Merlin’ (

plate 3

) gave us a good idea about how to proceed. The bed was demountable because Edward I was constantly travelling round the country. His servants took it apart in order to transport it from castle to castle, and the chains held the whole thing together when it was re-erected.

We have another glimpse of the colour and grandeur of a late-medieval bed from Geoffrey Chaucer, who, at one stage in his career, was ‘Yeoman Valet to the King’s Chamber’. In this position he was responsible for bed-making, so he knew what he was talking about when he described a luxurious gold-and-black bed:

… of downe of pure dovis white

I wol yeve him a fethir bed,

Rayid with gold, and right well cled

In fine black satin

d’outremere

[from overseas].

Even towards the end of the medieval period, though, grand beds carved in wood were still few and far between. A ‘pallet bed’ was most people’s accustomed lot. It was essentially a wooden box, perhaps with short legs, that could be easily carried from room to room as the number of servants or guests requiring accommodation ebbed and flowed. Pallet beds were so simple and practical they endured for centuries. At the Elizabethan Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, an inventory from 1601 shows that a folding bed was kept on the landing of the stairs for some poor soul, and that there was a pallet even in the scullery. The memoirs of a valet who worked at an Irish country house in the 1860s record similar sleeping arrangements, though by then they must have been exceedingly old-fashioned: ‘There were three or four beds in a room. Many of the men had folding or press beds here and there in the pantry and the hall.’

But the Tudor age also saw one of Europe’s greatest inventions take on a fixed form. The four-poster bed was often the most expensive item in a house, and was an essential purchase upon marriage. (If you were lucky, you inherited yours from your parents.) Its canopy protected you from twigs or feathers falling from a roof which might lack a plaster ceiling. Its woollen curtains provided warmth, and also

some

privacy. It’s very likely that even in a middle-ranking Tudor household the master and mistress would be sharing their bedroom with children or privileged servants using pallet beds or even wheeled truckle beds that lived underneath the four-poster during the daytime.

On a Tudor four-poster, the mattress lay upon bed-strings made up of a rope threaded from top to bottom and side to side. This rope inevitably sagged under the sleeper’s weight and required regular tightening up, hence the expression ‘Night, night, sleep tight’.

Pictures of pre-modern people in bed often show them in a curious half-sitting position. Propped up against pillows and bolsters, they look rather uncomfortable, and one wonders if they actually slept like that. Perhaps the answer is that art did not mirror reality, and that artists always positioned their models to get the best possible view of their faces. (Also it isn’t likely, as so many contemporary images seem to suggest, that medieval kings slept in their crowns.) But I think the explanation for the pose is that beds strung with rope cannot fail to dip in the middle and feel rather like hammocks. In fact, sleeping on one’s front is well-nigh impossible in a rope-strung bed, as I discovered when I spent the night in the medieval farmhouse at the Weald and Downland Museum.

On into the seventeenth century people were still accustomed to share their beds. When the daughter of Lady Anne Clifford was nearly three, her maturity was measured with three changes in her daily life: she was put into a whalebone bodice, left free to walk without leading strings, and allowed to sleep in her

mother’s bed. Sharing a bed was the action of a grown-up, not (as now) of a child.