Kabbalah (11 page)

M O D E R N T I M E S I : T H E C H R I S T I A N K A B B A L A H

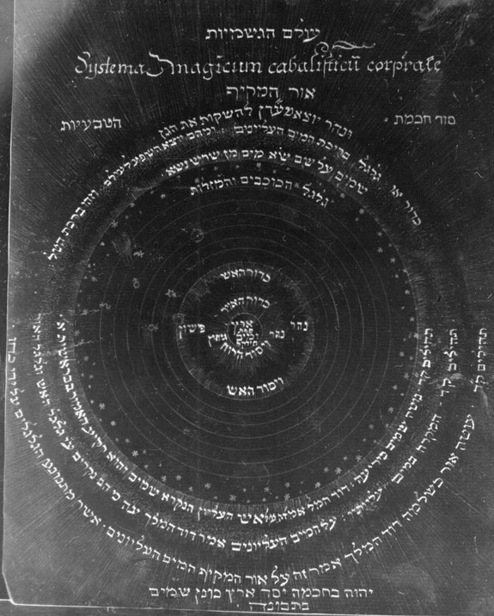

kabbalistic concepts. In England, some thinkers in the Cambridge school of neo-Platonists—Henry More and Robert Fludd, among many others—used the kabbalah. In Holland, the numerous works of the theologian Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont, reflect an extensive use of kabbalistic materials, and it seems that he collaborated in this field with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (1646–1716). In many of these and other works the speculations based on kabbalistic ideas were integrated with astrological theories and especially alchemical ones, presenting the kabbalah as one of those occult doctrines.

Gershom Scholem described the work of the German philosopher Franz Josef Molitor (1779–1861) on the philosophy of tradition as “the crowning and final achievement of the Christian kabbalah.”

Since the seventeenth century, kabbalah, in different spell-ings, became a common term in European languages, indicating in an imprecise manner anything that was ancient, mysterious, magical, and to some extent dangerous. It became an adjective that was used in various ways, often without any clear connection to either the Hebrew sources or even the original works of the Christian kabbalists. “Cabal” was used to describe a secret group of people contemplating mischief. During the Enlightenment interest in this esoteric, magical doctrine diminished, but it returned forcefully with the renewed attention to myths and secrets in the nineteenth century. References to the kabbalah are found in popular, pseudoscientific works, as well as in treatises dedicated to various forms of mysticism.

One of the most meaningful results of development of the Christian kabbalah was the separation between kabbalah and Judaism; these two terms could not be regarded as necessarily dependent on each other. In Christian culture, one can be an adherent of the kabbalah without being Jewish, and it is even possible to combine kabbalah and anti-Semitism. Carl Gustav Jung could thus combine admiration of the kabbalah with enmity toward Jewish culture. When this sense of the 67

K A B B A L A H

separateness of the kabbalah returned to Jewish context, in the late nineteenth century and more intensely during the twentieth century, it sanctioned a division between kabbalah and Jewish orthodoxy and observance of the commandments.

Adherence to kabbalah became a substitute for the acceptance of Jewish tradition as a whole. This enabled people to per-ceive themselves as being connected to Jewish traditional culture without observing the elements of the tradition that they rejected.

Whereas the early reformers of Judaism in the nineteenth century found the spiritual dimension of Judaism through adherening to rationalism and social ethics, groups of Jews who sought a nonorthodox spiritual, yet traditional, type of Judaism tended to adopt kabbalah, or what they believed to be kabbalah, as a central aspect of their worldview and religious rituals. This was evident, for instance, in some secular kibbut-zim in Israel that vigorously rejected the orthodox way of life, but introduced kabbalistic terms, images, and rituals into their culture, representing their ties to Jewish cultural tradition. A similar phenomenon was prominent among the

havurot

(the Hebrew word for “groups”) of young Jews in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s; kabbalah was often combined with some neo-Hasidic expressions, endowing their spiritual experiences with an aura of Jewish traditionalism while de-emphasizing, or even rejecting outright, the authority of the halakhah. Since the 1980s these groups and tendencies were integrated with the atmosphere of the New Age culture. Adherence to some elements of kabbalistic terminology enabled these

havurot

to develop a Jewish identity without the obligation to observe the strict rules of Jewish orthodoxy. The kabbalah was thus established as a traditional Jewish substitute to the attractions of Zen Buddhism, Transcendental Meditation, and other alternative religions and spiritual practices. In many cases the kabbalah was identified with these and other spiritual fashions that originated in the East and became an integrated component of Euro-68

M O D E R N T I M E S I : T H E C H R I S T I A N K A B B A L A H

pean and American culture, especially among students and young academics on university campuses, where young Jews assembled in quest for spiritual identity. The term “kabbalah”

did not carry the reservations and ambiguous attitudes that non-Jews had toward the term “Judaism” and the traditional expressions of Jewish orthodoxy.

69

K A B B A L A H

9 According to Lurianic thought, the structure of the ten sefirot also

represents the basic structural characteristic of everything that exists, be it spiritual or material.

70

M O D E R N T I M E S I I : S A F E D A N D T H E L U R I A N I C K A B B A L A H

6

Modern Times II:

Safed and the Lurianic Kabbalah

Following the destruction of the great Jewish center in the Iberian peninsula in 1492, groups of Jewish intellectuals gradually congregated in the small town of Safed in the Upper Galilee, attracted by the traditional belief that Rabbi Shimeon bar Yohai, the main figure of the Zohar, was buried in the nearby village of Miron. The Jewish community in Safed was very small (hardly two thousand families in the sixteenth century), but it included many of the most inspired and ambitions minds of the period.

A pioneering spirit imbued the community, which believed itself to be the religious leader of the Jewish people. In the 1530s the town’s scholars were engaged in a revolutionary endeavor.

They intended to reconstitute the traditional ordination of rabbis, which started with Moses on Mount Sinai and continued through biblical and talmudic times but was discontinued in the beginning of the Middle Ages, when it was relegated to the realm of messianic redemption. The Safed scholars believed that they should actively prepare for the redemption, and the renewed

semikhah

(ordination) was carried out there for several generations. The rabbis of Jerusalem and Egypt did not accept it, and it seems that the venture ended in failure.

Rabbi Jacob Berav was the leader of the movement, and one his ordained students, Rabbi Joseph Karo, is the author of the most normative and dominant work of religious law in 71

K A B B A L A H

modern Judaism—the

Shulhan Arukh

(The Laid Table). Karo was a kabbalist as well as a lawyer, and he wrote an extensive kabbalistic work that he claimed was dictated by a divine messenger, a

magid

, whom he regarded as a manifestation of the

shekhinah

. Several great writers, all of them kabbalists, were active in Safed, among them Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, Rabbi Moshe Alsheikh, and the greatest kabbalist of the time—Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, who wrote numerous kabbalistic treatises in addition to his multivolume commentary on the Zohar,

Or

Yakar

(Precious Light).

The community of Safed distinguished itself by strict adherence to the ethical and ritualistic commandments, believing that scrupulous observance would enhance the arrival of the era of redemption. They developed a sense of communal interde-pendence: religious perfection was everyone’s endeavor, and anyone who transgressed harmed not only his own soul but hurt everybody by delaying the redemption. They organized several “repentance groups,” in which the members would consult and assist each other in striving for religious and ethical achievements.

The very concept of repentance underwent a radical transformation: it no longer represented the return to observance after a transgression, but a way of life, one of complete dedication to extreme orthodoxy, repenting not only one’s own sins but the sins of all others, past and present. The conception seems to have been that God does not deal only with individuals, but with the people as a whole, and redemption is to be achieved by communal or even national perfection. Each individual is religiously responsible for the sins and transgressions of everyone else, living and dead, and therefore there cannot be any limit to the sacrifices and efforts of repentance. Several Safed scholars went as far as inflicting themselves with pain and wounds, including self-immolation, which is very rare in Jewish practice.

Isaac Luria, who revolutionized the kabbalah in this period, arrived in Safed in 1570 when these practices were at their peak.

He was born in Safed in 1534, but his family migrated to Egypt, where he grew up and acquired his traditional and kabbalistic 72

M O D E R N T I M E S I I : S A F E D A N D T H E L U R I A N I C K A B B A L A H

education. When he returned to Safed a group of disciples assembled around him. Rabbi Hayyim Vital Klippers, who was already a well-known Safed scholar, headed the disciples, who believed that Luria’s soul was often uplifted to the divine realms, where he studied great secrets in the celestial academy of Torah.

Although we have a few fragments of his writing discussing portions from the Zohar, he did not write much. He explained his reluctance to write by the enormity of the visions that were before his eyes. It was like a great river, he is reported as saying, which he could not control and let it flow from his tiny pen.

Luria died in a plague two years after his return to Safed, in 1572, at the age of thirty-eight. Some of his disciples explained his early death as punishment for revealing forbidden secrets, thus enhancing the prestige of his teachings. Others maintained that he was the Messiah Son of Joseph, the commander of God’s armies who was destined to die just before the Messiah Son of David redeems the world. (Rabbi Hayyim Vital believed this second role to be his, and he asserted that Luria had revealed to him his own messianic destiny.) Luria’s prestige grew in the next decades, a body of hagiographic tales relating his miraculous knowledge was told by those who knew him, and his disciples assembled his teachings in several versions.

The most important studies of Luria’s teachings were presented by Gershom Scholem and Isaiah Tishby in 1941, and since then, while we have many books and articles dealing with particular problems and aspects of Luria’s teachings, the main picture that they drew is still dominant. Further studies may cast some doubts, but as of now presenting their studies is the best that we can do. The reader should not accept the following description as a final word; it may be revised, but today we do not have any comprehensive alternative.

The Withdrawal: Zimzum and Shevirah

Isaac Luria dared, unlike most theologians and philosophers, to put in the center of his worldview the most basic questions, 73

K A B B A L A H

which are so often avoided: Why everything? Why does God exist? Why did the creation occur? What is meaning of everything? He gave to these questions a most radical and revolutionary answer, expressed in daring mythological concepts and terms. The most innovative concept that lies at the heart of Luria’s teachings is the imperfection of beginning. Existence does not begin with a perfect Creator bringing into being an imperfect universe; rather, the existence of the universe is the result of an inherent flaw or crisis within the infinite Godhead, and the purpose of creation is to correct it.

The initial stage in the emergence of existence is described by the Lurianic myth as a negative one: the withdrawal of the infinite divine

ein sof

from a certain “place” in order to bring about “empty space” in which the process of creation could proceed. The Lurianic mystics called this process

zimzum

(constriction), a term taken from talmudic literature indicating the constriction of the

shekhinah

in the space between the images of the angels on the holy ark in the temple in Jerusalem. Here, however, it is not constriction into a space but withdrawal from a space, creating what Luria called, in Aramaic,

tehiru

(emptiness). Into this empty region a line of divine light began to shine, gradually taking the shape of the structure of the divine emanations, the

sefirot

.

Luria made use of a concept developed a generation before him by Moses Cordovero, who attempted to explain the individuality and functional differences between the divine emanations. The question he addressed was: if the

sefirot

are divine, how can they be different from each other? There cannot be differentiation within divine perfection. His response was: the

sefirot

are to be conceived like vessels (

kelim

); the essence within them is pure divine light, while the vessels are “made” of somewhat courser divine light, which gives them “shapes,” expressing their individuality and specific functions. This is reminiscent of the Aristotelian concept of the matter and form of which everything is made; yet Aristotle ascribed a higher spiritual 74