Kabbalah (14 page)

It was an endeavor similar to that of the early Christians, who interpreted the writings of the ancient prophets of Israel as predicting the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Christ.

Another example was the interpretation of the Bible and the Talmud by the early kabbalists, who discovered in every verse and rabbinic statement references to the system of the

sefirot

and the concept of the feminine

shekhinah

. The Sabbatian writers often referred to the same verses that Christian commentators used concerning the messiah, and some of their opponents pointed out the similarities between Sabbatian and Christian conceptions of the role of the messiah as an intermediary and the verses that were presented in support of these ideas. These similarities increased after Shabbatai Zevi’s death in 1676, when both Sabbatians and Christians presented concepts of messianism in which the redemption had already occurred, and in which the messiah will return to signify the completion of the process. It is interesting to note that contemporary writers who find it very important to present links between the kabbalah and Christianity somehow tend to ignore the prominent and 89

K A B B A L A H

obvious phenomenological similarities between Sabbatianism and early Christianity.

Another aspect in which a close parallel between Sabbatianism and Christianity existed relates to the concept of the Torah and its commandments as presented by Nathan of Gaza.

Using Lurianic terms indicating the various layers of existence, Nathan described the Torah as given by Moses and followed by Jews in all generations as the Torah reflecting the layer of “creation” (

torah de-beriah

). The Torah that is now taking its place is the Torah of the highest spiritual layer, that of divine emanations (

torah de-azilut

). The physical commandments, the numerous rituals, are all part of the lower stratum of the Torah. The higher one, the Torah of the messianic age, is spiritual in character, relating to faith and enlightenment rather than the subjugation of the body. The strange behavior of Shabbatai Zevi, culminating in his conversion, was a reflection of the higher, spiritual Torah. (The similarity between these ideas and the Pauline interpretation of the biblical commandments as relating to the premessianic era, and the idea that they should now be reinterpreted in a spiritual manner, is more than remarkable.) These concepts open the gate widely for antinomian commentaries on Jewish law. It was now possible to denounce the halakhah as relevant only to the unredeemed world, while new vistas of spiritual freedom were open for the believers.

Several thousands of Sabbatians followed Shabbatai Zevi in the last decades of the seventeenth century and converted to Islam. Their Turkish neighbors designated them as

doenmeh

(foreigners), and they continued their sectarian existence for centuries, to this very day. Most Sabbatians, however, remained within Jewish communities, and created an underground of believers in all strata of Jewish society, simple people, intellectuals, and rabbis. They imitated their messiah in a kind of “sacred hypocrisy”: they pretended to be orthodox Jews, adhering to the ancient exilic tradition, while secretly they worshiped 90

M O D E R N T I M E S I I I : T H E S A B B A T I A N M E S S I A N I C M O V E M E N T

the messiah and the Torah of the age of redemption. They expressed this in various ways. A common one was to celebrate the birthday of the messiah, which occurred on the day of mourning and fasting for the destruction of the temple—

tisha’a

be-Av

; when everybody was crying and praying they celebrated the end of the exile and the coming of the messiah.

We know of a score or more separate Sabbatian sects in Judaism in the late seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth. Their teachings were diverse, as were their practices. There were several groups that traveled to Jerusalem to await the return of the messiah. Others assembled around leaders who claimed to be the heirs or reincarnations of Shabbatai Zevi. There was no central authority or organization, nor any normative theology. Several writers produced books relating visions and messianic experiences. Some groups were led by messianic figures, who were not directly related to the Sabbatian tradition. The existence of these heretical sects hiding in many communities evoked a reaction: there were several rabbis who dedicated themselves to the hunting and discovering Sabbatian believers and identifying books reflecting a Sabbatian worldview. A bitter controversy arose in the 1730s when the chief rabbi of Prague, a prominent scholar, Rabbi Jonathan Eibschutz, was accused of being a secret believer in Shabbatai Zevi—an accusation that modern scholarship has proved to be correct.

One of Scholem’s main theses was the observation that this profound crisis that traditional Judaism was undergoing in the eighteenth century served as a basis for the emergence of the enlightenment movement in Judaism, which preached the integration of Jews in European society and culture. According to him, the walls of the Jewish ghettos in Europe fell down from within, before they were breached from the outside by the process of the emancipation of European Jews. The traditional norms lost their power under the onslaught of Sabbatian ideas, and prepared Jews for a new era of freedom and 91

K A B B A L A H

openness. This is a profound thesis, even though there are very few details that can be presented to prove it.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, Jacob Frank, a Pole who claimed to be a reincarnation of Shabbatai Zevi, presented a radical, heretical interpretation of the concept of the new, spiritual Torah. One of the slogans that he propagated was “the denial of the Torah is the true expression of adherence to it.” Everything in traditional law has now to be re-versed, and prohibitions are now positive commandments.

Prohibited erotic behavior is demanded in the present, the age of the redemption. He developed a visionary, anarchistic worldview, which demanded the destruction of the present, unredeemed world to make way for the messianic one. His radical heresy horrified the rabbinic authorities of the Jewish communities, which excommunicated the sect, known as Frankists, in the strongest terms. Jacob Frank approached the Catholic Church in Poland and entered into a prolonged process of ne-gotiations concerning the terms of the sect’s conversion, insisting on keeping the sectarian structure of his believers. In this process the Frankists twice faced Jewish rabbis in disputa-tions organized by the church, in 1757 and 1760; in the latter year Frank and several thousands of his adherents converted to Christianity. He established his court in Offenbach, near Frank-furt, and many of his believers became active in the European wars that followed the French Revolution. The Frankists were the most radical form of Jewish heresy, rebellious and destructive, and the most extreme example of antinomianism. The intensely orthodox doctrines of Isaac Luria had been turned in this case into a complete denial of Jewish laws and norms.

Some of the mystical messianic ideas developed in the various sects of the Sabbatians survived the decline of the movement at the end of the eighteenth century. They expressed, in different manners, several directions in which the kabbalah developed, the most important among them being the theology of the modern Hasidic movement, which is the most prominent expression of the kabbalah in contemporary Judaism.

92

M O D E R N A N D C O N T E M P O R A R Y H A S I D I S M

8

Modern and Contemporary Hasidism

The kabbalistic tradition prevails in orthodox Judaism today within certain circles inside the Hasidic movement and among some of the movement’s opponents. The schism between Hasidism and the

mitnagdim

(opponents) is the most significant historical phenomenon in modern Jewish traditional religious culture. It has characterized orthodox Judaism in the last two centuries, despite the great upheavals, catastrophes, and transformations that occurred during this period in Jewish life and destiny. In everyday English usage “Hasidim” often relates to all ultraorthodox Jews, ignoring, or perhaps unaware of, the conflict between Hasidim and the Opponents. In fact Jewish ultraorthodoxy in the United States, Israel, and Europe is divided about equally between Hasidim and Opponents sometimes called “Lithuanians,” because that country was the center of the opposition to Hasidim in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Despite the depth of this schism—so profound that marriages between adherents of the two factions are very rare—the groups are united in their fundamentally kabbalistic worldviews. The conflict can be conceived as one raging between two conceptions of the kabbalistic tradition. While the Opponents are es-sentially loyal to the Lurianic kabbalistic concepts, the Hasidim introduced some new concepts, especially concerning mystical leadership and messianism, into their version of the kabbalah.

93

K A B B A L A H

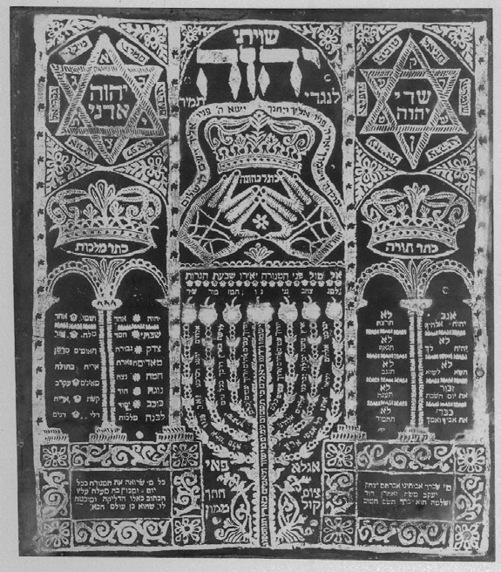

11 The holy name of God should constantly be before the eyes of the Hasid.

94

M O D E R N A N D C O N T E M P O R A R Y H A S I D I S M

There is no basis, however, to the common misconception that the Opponents have a more “enlightened” and “rational”

worldview, while the Hasidim are more inclined to indulge in kabbalah and mysticism. The leader of the Opponents in the late eighteenth century, Rabbi Eliyahu the Gaon of Vilna, was a kabbalist who wrote commentaries on several classics of this literature, and his disciples were immersed in traditional kabbalistic ideas and terminology. The concepts of God, the universe, and humanity as formulated by the Lurianic kabbalah still dominate the theologies of both the Hasidim and the Opponents.

Rabbi Israel Ba’al Shem Tov (1700–1760), who was known by the acronym Besht, founded the Hasidic movement in southern Russia. He was a kabbalist who wandered from place to place, preaching and serving as a healer and a magician. The movement took shape under the leadership of his main disciple, Rabbi Dov Baer of Mezheritch, who was known as the Great Magid, or preacher. Neither the Besht nor the Magid, who died in 1772, wrote books; their disciples collected and published their teachings. The Magid’s teachings include an emphasis on the individual’s communion with God (

devekuth

), and on introducing spirituality into the most mundane aspects of human life.

The ideas of the Besht and the Magid and their followers were presented in a popular, exoteric language that avoided technical kabbalistic discourse; this gave the young movement an image of a popular, revivalistic spiritual phenomenon.

The young Hasidic movement was denounced and excommunicated in 1772 by the then great leader of rabbinic Judaism, Rabbi Eliyahu the Gaon of Vilna. This decree was renewed several times in subsequent decades and is still in force. It is probable that one of the reasons for this harsh treatment of the Hasidim by the rabbinic establishment of that time was the fear of a renewed eruption of Sabbatian heresy. Another was the fear that by emphasizing a mystical relationship with God, the Hasidim might weaken the adherence to the study of the Talmud, which was regarded as the supreme expression of spirituality in most eastern European communities.

95

K A B B A L A H

Rabbi Dov Baer assembled around him a most unusual group of great teachers and charismatic leaders, who spread out after 1772 and established dozens of Hasidic communities throughout eastern Europe. These communities were modeled on the court of the Magid, and his teachings served as a starting point, though many of these disciples developed original and innovative religious and social conceptions. By the first decades of the nineteenth century, European Judaism was split between the Hasidim and their Opponents, often dividing communities into groups engaged in constant conflict. This situation prevails today in the orthodox Jewish centers in Israel and the United States. In most places they live in separate neigh-borhoods, keeping contact among them to a minimum. Despite this schism, both camps base their religious outlook on the teachings of the kabbalah, and many of their leaders write kabbalistic commentaries, treatises, and homiletical and ethical works.

Hasidic Dynasties and the

The teachings of the Besht and the Magid emphasized the centrality of communion with God, achieved especially by prayer, and the spiritual efforts required to correct evil and uplift it to its good, divine origins. Their main message was “there is no place from which He is absent,” a kabbalistic panentheistic system. (While pantheism postulates that everything is God, panentheism claims that God is inside everything.) The movement, in its beginnings, was a pietist, spiritual one, including probably some messianic aspirations, led by charismatic preachers. Yet by the end of the eighteenth century, it evolved into a loose network of independent communities, each led by a

zaddik

, a mystical leader. Most of the founding fathers of these sects or communities were the charismatic disciples of the Magid. However, this mode of leadership was not continued after the first generation. The early leaders established dynasties (often known 96