Kabbalah (13 page)

The

zimzum

was often conceived as an expression of divine benevolence, of God diminishing himself in order to be able to be perceived and understood by his creatures.

Outside of Judaism, in Christian Europe, the concept of the

tikkun

made no meaningful impression, but the term “

zimzum”

seems to have impressed several European thinkers, and it became a meaningful one within Christian kabbalah and other segments of European esotericism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Other aspects of Lurianic kabbalah may have had some relevance to the development of religious ideas in early modern Europe. One of them is the Lurianic concept that the structure of the ten

sefirot

is not only a description of the original ten divine hypostases, but they represent the basic structural characteristic of everything that exists, be it spiritual or material. The concept that the human soul reflects this structure is found in the writings of medieval kabbalists, but the Lurianic writers, especially Rabbi Hayyim Vital, extended it to include all aspects of existence. The ancient concept of

harmonia mundi

was extended by Vital to encompass the nature of 81

K A B B A L A H

creation as a whole. The intense individual characteristics of each

sefirah

, as portrayed in the Zohar, were submerged in this doctrine and transformed into principles that constitute the building blocks of every aspect of existence.

It is paradoxical that the core of the mythical description of the divine powers in the medieval kabbalah has been replaced in the Lurianic worldview by a kind of scientific system. The nature of each entity is decided not by its structure—because everything is made of the same components—but by its place in the detailed hierarchy of beings descending from the supreme Godhead to the animals and stones in a field. In order to define an entity one has to pinpoint its place and position: the element of

hod

within the realm of

keter

within the stage of

yesod

in this or that realm. The myth of

zimzum, shevirah,

and

tikkun

did not prevent Vital and others from describing existence in a quantitative, scientific hierarchy of identical elements identified by their relative position to each other. A similar attitude can be found in Vital’s detailed discussion of the human soul.

The concept of reincarnation (

gilgul

) became central in the psychological doctrines of the Lurianic school, perhaps for the first time in the history of the kabbalah. There are five strata in the soul, reflecting the structure of the

sefirot

; each of these components has its own history, and each wanders from body to body, from generation to generation, independent of the other parts. Each soul, therefore, is a meeting of parts that have their own history and experiences. In his book of visions, Vital described the detailed history of his own soul, the soul of the messiah, which first came to existence in the body of Cain, and has been moving from body to body until it was re-collected in Vital’s body. Vital claims that this information was given to him by Luria himself, whose greatness was expressed by his knowledge of the history of every soul.

These and other Lurianic concepts have occupied the de-liberations of kabbalists for the last four hundred years. Yet the main message of Lurianism, which was embraced by Judaism 82

M O D E R N T I M E S I I : S A F E D A N D T H E L U R I A N I C K A B B A L A H

as a whole, was the tension between exile and redemption, at the center of which stands every individual who seeks to strengthen the powers of good and weaken those of evil by his religious and ethical daily behavior. The sense of a unified fate and collective responsibility and waiting for the imminent completion of the

tikkun

and the beginning of the messianic age became paramount in Jewish culture. In the middle and second half of the seventeenth century these spiritual conceptions became a historical force that changed Judaism in the most fundamental way.

83

K A B B A L A H

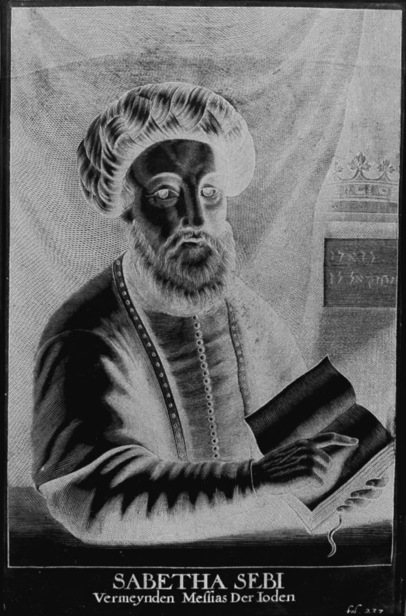

10 Born in Smyrna, Shabbatai Zevi was the great leader of the messianic movement who convinced many he was the messiah.

84

M O D E R N T I M E S I I I : T H E S A B B A T I A N M E S S I A N I C M O V E M E N T

7

Modern Times III:

The Sabbatian Messianic Movement

The enormous burden that Lurianic teachings placed on every individual was characteristic of the pioneering, devoted community of spiritualists that dominated the unique culture of sixteenth-century Safed. When the teachings of Safed spread to Jewish communities throughout the world, ordinary people were faced with this extraordinary responsibility for the fate of God, the universe, and the Jewish people. This was very diffi-cult to sustain, and during the messianic upheaval in the seventeenth century the concept of a mystical-messianic leader—a divine figure who could undertake a part of this responsibility and direct the people toward the completion of the

tikkun—

emerged. The person who brought about this meaningful modification of the Lurianic kabbalah was Nathan of Gaza, who is known in history as the prophet of the messiah Shabbatai Zevi.

Shabbatai Zevi was born in Smyrna, one of the great centers of Jewish culture in the Ottoman Empire, in 1626. He was versed in kabbalah, and during his youth he began to develop his messianic pretensions. There was nothing unusual in that; there were several people who believed in their own messianic destiny in most Jewish centers. He declared his mission; behaved in strange, provocative ways; and was disregarded, ridi-culed, and often banished from various communities in Turkey and other countries in the Middle East. In 1665 he met in Gaza 85

K A B B A L A H

a young Lurianic kabbalist, twenty years his junior, who came to believe that Shabbatai Zevi was indeed the messiah. This young man, Nathan, described himself as a prophet and began to preach, in various ways, that the process of the

tikkun

had been completed and that the messiah had already appeared.

He “discovered” ancient documents supporting this, and told about his visions concerning the arrival of the age of redemption. Most people who heard about his prophecy received it as authentic. There was nothing unusual in a person pretending to be a messiah, but the claim to prophecy, coming from the Holy Land, was a new experience for Jews. Because the Talmud states that there is no prophecy but in the land of Israel, they tended to listen and believe. Nathan’s message was expressed in Lurianic, orthodox terms, and did not seem to include any element that aroused suspicion. His first pamphlet was a call for repentance, written in the most traditional and orthodox terms. During the year 1666, Nathan’s messianic prophecy spread quickly from synagogue to synagogue, first in the Ottoman Empire and then Christian Europe. Many accepted it with great enthusiasm, and very few found any reason to hesitate. By the summer of 1666 it seemed that the whole Jewish world was in the grip of messianic fervor.

Nathan’s endeavor only succeeded because it was an expression of the kabbalah’s dominance in Jewish religious culture, and because of the eruption of messianic interest in Judaism following the crisis of the expulsion from Spain. The numerous leaders and thinkers who shaped the theologies of the scores of messianic groups active from 1666 to the beginning of the nineteenth century were all integrated in kabbalistic thinking, and in most cases in Lurianic kabbalah, which they developed according to their particular aspirations and needs. This was true not only for Jewish Sabbatians, as the followers of Shabbatai Zevi were known, but also included those who converted to Christianity and Islam, and continued to cherish their unique kabbalistic-messianic conceptions in the foreign cultural context.

86

M O D E R N T I M E S I I I : T H E S A B B A T I A N M E S S I A N I C M O V E M E N T

In 1665–1666, Nathan of Gaza presented his adaptation of a kabbalistic terminology and worldview into Sabbatian messianism. His worldview was a modification of Lurianic kabbalah, introducing into the Safed system a new element, the role of the messiah in the process of the

tikkun

, the mending of the original catastrophe that made the world a realm ruled by evil. According to Nathan, it was not enough to follow the Lurianic precepts of utilizing religious ritual and observance to uplift the scattered sparks of divine light and return them to their proper place in the divine world. There is, he argued, a core of evil, which human beings cannot overcome on their own. In the kabbalistic anthropomorphic metaphor, this core is described as the “heel of evil,” the most coarse and tough part of the body of evil. In order to overcome this, a divine messenger, with superhuman powers, is needed. This messenger will collect the spiritual power of the whole people and utilize it to overcome the aspect of evil that cannot be vanquished directly. He believed that the messiah, whom he identified as Shabbatai Zevi, was the incarnation of the sixth divine

sefirah

,

tifferet

, and that he came to the world for this purpose.

Nathan proclaimed that each Jew should give the messiah spiritual force in the form of faith in him, and the messiah will then focus the powers of the whole people to achieve the final vic-tory over the forces of evil. Thus, Nathan introduced into Judaism the concept of a mediated religious relationship with God, giving the messiah (for the first time in a millennium and a half) the role of being the intermediary between the worshipper and the supreme Godhead, and allotting to him a position of an incarnated divine power. He did that on the basis of kabbalistic concepts, and the wide approval these ideas enjoyed reflected the widespread influence of the kabbalah in the seventeenth century.

Nathan’s theology of the messiah was the complete opposite of Lurianic teachings, even though he used Lurianic terminology and worldview. Luria and his disciples described a direct relationship between man and God, and viewed the 87

K A B B A L A H

tikkun

as the involvement of every individual in the process of redemption—a most heavy burden that ordinary people found hard to undertake. Nathan, on the other hand, positioned the divine messiah in the middle, mediating between the worshipper and the task of the

tikkun

. Every Jew has to express his complete faith in the messiah; the Sabbatians often designated their creed by the term “

emunah”

(faith). The messiah transforms this spiritual power into a weapon to vanquish evil and redeem the universe.

The theological challenge facing Nathan of Gaza and other Sabbatian thinkers changed dramatically late in 1666, when Shabbatai Zevi was summoned to the palace of the Ottoman sultan. He emerged from the meeting wearing the Muslim cap.

Having been threatened, Shabbatai Zevi did not hesitate for long before converting to Islam. Judaism was suddenly faced with a situation in which the messiah committed the worst possible sin that generations of Jews were educated to avoid.

One has, when faced with a demand to convert, to become a martyr and “sanctify the holy name” rather then betray one’s God, people, and tradition. Shabbatai Zevi, who should have been the example of religious perfection and who was regarded not only as a divine messenger but also as a divine incarnation, did the exact opposite.

Most Jewish historians in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries regarded the conversion as the end of the Sabbatian movement, and described the groups of Sabbatians that continued to be active as “remnants,” having no historical significance. It was Gershom Scholem who proved in several books and many studies that Sabbatian messianism continued to ex-ert meaningful influence for the next 150 years, and that it contributed to the shaping of Jewish culture in modern times.

Scholem explained that religions are not devastated by a historical paradox but rather thrive on it. The execution of the messiah as a common thief did not put an end to Christianity; it was actually its beginning. In a similar way, the paradox of a converted messiah was the beginning of a new religion within 88

M O D E R N T I M E S I I I : T H E S A B B A T I A N M E S S I A N I C M O V E M E N T

Judaism, and sects of believers continued to thrive also within Islam and Christianity.

It was Nathan’s task to explain the conversion to the believers. He insisted that his prophecy was true, and that the

tikkun

had indeed been completed and the age of redemption had actually begun. The conversion was explained as a neces-sary stage in the struggle against the continued resistance of the powers at the core of evil’s realm. These powers cannot be vanquished from the outside: the messiah had to pretend to be one of them, to assume a disguise, in order to enter their realm and overcome them from the inside. One of the most fascinat-ing and meaningful processes that occurred as a result of Shabbatai Zevi’s conversion was the intense re-reading and reinterpreting of the ancient sacred texts—the Bible, the Talmud, and the Zohar—and the “discovery” of numerous verses and statements that indicate the necessity of the messiah’s conversion to an “evil” religion.