Languages In the World (58 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

We spent the first half of Chapter 2 describing the ways language loops in several directions at once, namely around: (i) cognitive domains, (ii) landscape, (iii) cultural contexts, (iv) itself, and (v) discourses and ideologies. If even one of these loops gets disrupted, the entire fabric of the language can start to unravel. For instance, loss of a landscape or an ecosystem can endanger the speakers and their languages as much as it can other flora and fauna living there. So can a belief system, if a group decides their language is no longer worthy of passing down to the next generation. It can also happen that population movements alter the cultural context in which a language is spoken, and speakers shift from one language to another. In this section, we describe examples of the three types of language loss just described, and they have been labeled (i) sudden death, (ii) radical death, and (iii) gradual language shift in multilingual settings (Campbell & Muntzel 1989).

To the south of Australia, the island of Tasmania was once home to the Palawa people and their language. For nearly 40 millennia, the Palawa people developed mostly in isolation from Aboriginal Australia and the rest of the world. The Palawa language likely formed a dialect chain running across the Tasmanian island. The varieties spoken on the northern, western, and eastern extremes of the island were more than likely mutually unintelligible. Palawa culture was integrated with and embedded in the ecosystem of Tasmania. Coastal regions provided shellfish and crustaceans for consumption. Coastal plains and dense inland forests provided opportunities for foraging and hunting. Clans stayed mostly in their own regions of the island but moved about for food according to the seasons. Palawa life and language were thus linked with landscape, rhythms of movement, and cultural practices, which had been worked out over the millennia in a way one could say was well knit.

In 1803, the British arrived to build their colonies, and the Palawa ecosystem was thrown into immediate chaos. Free settlers and farmers were encouraged by the colonial government to take up permanent residence on Palawa land. Key hunting grounds became privately held farmland, and well-developed hunting routes and techniques were disrupted. In the realm of hunting, the Palawa now competed with the British, who hunted not only for sustenance, but also for furs and other resources. The

Palawa's primary dietary protein source quickly evaporated. And Palawa immune systems were unprepared for European disease. In 1829, an outbreak of influenza wiped out much of the Palawa population in the south and west of the island. Tuberculosis, syphilis, and other venereal diseases took their toll, as did conflict with free settlers and escaped penal colony convicts.

When the British arrived, there were as many as 5000 Palawa people living in Tasmania. After three decades of colonialism, some 95% of the Palawa had died or been killed; their population in 1833 had been reduced to 300. The last speaker of any Tasmanian language variety died in 1905. Although it took about a century to completely eradicate the Palawa language, it was functionally gone by 1843 when 99% of the speakers had died or been killed. Today, Tasmania is Australia's most English-speaking state (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1999).

In the 1920s, El Salvador was characterized by remarkable socioeconomic inequality. More than 90% of its private land was owned by a handful of powerful families, who were also heavily involved with the government. Coffee was a cash crop, and those who worked the coffee plantations were usually indigenous and always poor. The onset of the Great Depression and the corresponding collapse of the price of coffee made tense sociopolitical conditions between the classes worse. By the start of the next decade, the country was breaking under the weight of its own inequality. In 1932, indigenous groups â most notably the Pipil â joined forces with Communist political rebels to fight back.

At first, the indigenous uprising was successful. Towns were seized, and the political system was disrupted. The elite took note, and the Salvadoran military responded with force. Those assumed to be guilty of participation in the uprising were taken from their homes and killed by government soldiers. Indigenous physical appearance and indigenous dress were taken by the military as prima facie signs of culpability. Though only 100 people were killed in the popular uprising, the military response that followed it resulted in the death of some 25,000 people, mostly indigenous speakers of languages such as Cacaopera, Lenca, and Pipil.

Under these negative conditions, two ethnic communities â the Cacaopera and the Lenca â immediately abandoned their languages in favor of Spanish as a part of their survival efforts. Because they believed that speaking Cacaopera and Lenca in public linked them to indigenous identities, thus making them vulnerable to police and military intimidation, they simply stopped speaking those languages. And parents, believing that knowing the ethnic languages would be detrimental to their children's physical safety in the future, opted not to transmit their languages to their children. With this disruption in transmission, Cacaopera and Lenca made a rapid disappearance, called

radical

because it was in response to severe political oppression.

When linguists went to investigate the languages of El Salvador in the 1970s, they found a few people who could recollect certain words and phrases of Cacaopera and one speaker of Lenca. Pipil fared better than Lenca and Cacaopera on account of its larger number of speakers. Nevertheless, Pipil speakers were gradually abandoning their language in favor of Spanish.

When the British took control of Tanzania from Germany at the end of World War I, they made three decisions that would affect the vitality of more than 100 languages in the region for decades to come. First, they established English as the official language of the country and promoted its use in the domains of science and higher education, and in the upper levels of government. Second, they promoted the use of the widely spoken local Bantu language, Swahili, in lower levels of government and primary education. Finally, recognizing the administrative value of a widely understood lingua franca, they promoted the standardization of Swahili.

When the British selected English as the official language of Tanzania, they also provided the Tanzanian independence movement with a convenient foil. English was the language of the colonizers, and if colonialism should go, so should its language. Therefore, when the Tanganyika African National Union was formed in 1954, it rallied people for independence through the use of Swahili. When independence was achieved 10 years later, Swahili was the obvious choice for Tanzania's official language. Since independence, Swahili has become a powerful symbol in Tanzania's ongoing nation-building efforts. The fact that Swahili had undergone standardization and was already widely in use in the state domains of government administration and education meant that it was poised to spread quickly and deeply throughout the country. It is therefore the case that today the biggest threat to the indigenous languages of Tanzania is not from English but from another indigenous language, namely Swahili.

In the outskirts of the remote Kilosa District, many hours from the bustling Swahili-speaking cities of Dar es Salaam and Dodoma, a single narrow road leads to a series of villages high up in the mountains. Together, the villages are known as the Vidunda Ward, home to the Vidunda ethnic group. The Vidunda people speak a Bantu language of the same name. The only speakers of the language are those born in the Ward and a very few number of people from other ethnic groups who relocate there from neighboring wards. The Vidunda population is small and shrinking: there are some 10,000 people today, down from twice as many in the late 1960s. The fact that there are virtually no second language speakers combined with a dwindling population and the perceived economic value of Swahili has left Vidunda prone to cross-generational language shift, the gradual displacement of one language by another.

In Vidunda Ward, the shift to Swahili is well under way. Swahili is used rather than Vidunda for selling agricultural products in cities outside the ward, as well as in contact with government agencies, including those that enter the community, such as health organizations. Swahili is now the compulsory language of instruction in the schools, as mandated by the federal government of Tanzania. In Vidunda Ward, language shift to Swahili is complete in almost all formal domains, and formal language encounters in other domains are almost always in Swahili. The young are the most likely to use Swahili in the widest array of social domains. Matengo is a Bantu language related to Vidunda, which is also spoken in Tanzania. Although, with 160,000 speakers, Matengo is more robust numerically than Vidunda, the same types of conditions promoting language shift in the Vidunda Ward are also at work in Matengo communities.

If the current economic, political, and cultural conditions in Tanzania remain stable, it is likely that cross-generational language shift to Swahili will continue to affect ethnic

communities throughout the country, and mother-tongue languages will continue to disappear. Nevertheless, what will happen to Vidunda, Matengo, and more than 100 other ethnic languages in Tanzania is impossible to predict. The futures and fates of languages cannot be predicted in advance because languages are bound to human conditions, which are inherently unpredictable.

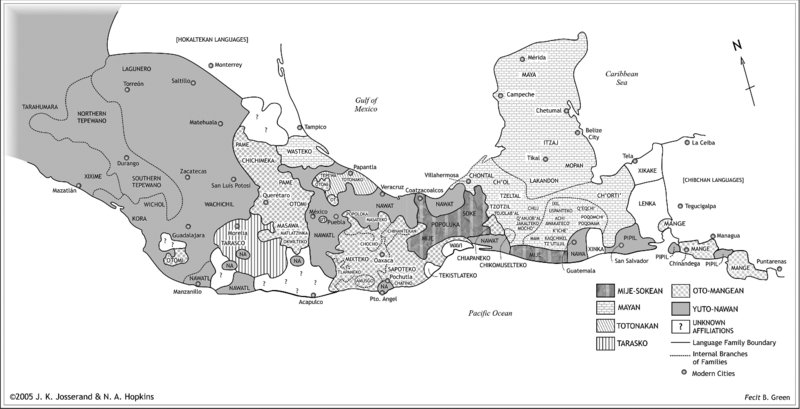

We said at the end of Chapter 7 that the area around the equator not only has the highest density of language diversity but also has the highest density of endangered languages. The historical conditions of the past 500 years â European colonialism, the rise of the nation-state, and the spread of compulsory education, among others â facilitated a first acceleration in the loss of languages in the world (

Map 12.1

). It also set the stage for the globalization that has led to a hyperacceleration of language attrition. Currently, about 25 languages disappear from use every year, roughly one language every two weeks. At this rate, more than 50% of the languages spoken in the world today will have fallen from use by 2100. Should the rate of attrition accelerate even further, as many as 90% of the world languages could be lost somewhere around the twenty-second century. It is possible to imagine that in 2115, the projected population of 11 billion people may speak somewhere between 500 and 1000 languages.

1

Map 12.1

Native languages of Mesoamerica, approximate distributions at European contact, circa 1500. A patchwork of Mayan, Yuto-Nahua, and Oto-Manguean languages.

In his book

The Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World's Most Endangered Languages

(2010), linguist K. David Harrison gives the term language hotspot to identify the regions with the greatest linguistic diversity, the greatest language endangerment, and the least documented languages. These language hotspots understandably coincide with the biodiversity hotspots described by biologists, such that species and ecosystems, languages, and the cultural knowledge linking languages to ecosystems are

simultaneously at risk for extinction. The triple extinction of ecosystem, language, and culture is completely consistent with the conditions that unravel the language loop.

The top five language hotspots are:

- Northern Australia;

- Highland South America;

- Northwest Pacific, North America;

- Siberia, Russia; and

- Oklahoma, United States.

Other highly endangered regions with great linguistic diversity are Eastern Melanesia (especially Papua New Guinea), West Africa, Greater South Asia, and Southern South America. Here, we focus on two of the top five language hotspots: Australia and Siberia.

William Brady is an elder in the Night Owl clan of the Gugu-Yaway people. He is also an expert hunter and knows his part of the outback better than almost anyone. When Harrison and his colleagues made a trip to Northern Australia, they met with Brady, who describes his language as including whistles and animal sounds. These exist so that hunters can speak to the animals. If they cannot speak to them, they are not good hunters. For Brady, there is a language of the bush, and if you do not speak it, you had better not go into it. Brady has long appreciated what many linguists have only fairly recently theorized as ethnosyntax: languages exist in an intricate web within the ecosystems where they are spoken. The Gugu-Yaway language is thus continuous with the bush, the species that inhabit it, and the cultural practices (hunting) that developed through living in it.

Gugu-Yaway is one of a hundred or more languages at risk for extinction in Australia, the top-ranking language hotspot in the world, owing to its great language diversity and great extinction risk. Others are Nangikurrunggurr âLanguage of the swamp people', Ngengiwumerri âLanguage of the sun and cloud people', Kalaw Kawaw Ya, Nigarakudi, Kulkalgowya, Magati Ke, and dozens more, each embedded in the ecosystem where it is grounded. For example, Harrison explains that the Nangikurrunggurr use what are called

calendar plants

as cues for gathering food. The bark of the gum tree, for instance, lets locals know when the sharks in the river are fat and may be hunted. This is namely when the bark peels easily from the trunk. Locals know to gather crocodile eggs along the riverbanks when the kapok tree blooms, and its seedpods release fluff into the air. This is the type of specialized knowledge that disappears when languages are lost.

The Tofalaria is a region in Eastern Siberia, Russia. Touching Central Asia, Tofalaria is one of the most remote parts of all of Russia. The region is home to the Tofa people, who speak a language of the same name. The Tofa live off the animals and vegetation provided by the Siberian forests, and from the milk of their most important animal, the reindeer. The Tofa are traditionally reindeer herders and even ride domesticated reindeer to do their hunting. The language has words for concepts such as âsmelling like reindeer milk' and âthree-year-old male uncastrated rideable reindeer.'

For the past 400 years or so, Russian has been encroaching on the languages of Siberia, which come from diverse language families. Tofa children today mostly speak Russian. As the language fades from one generation to the next, so does the intimate knowledge it encodes about the local ecosystem. With the exception of languages like Buryat and Yakut, most of the other languages of Siberia â about three dozen â are facing the same fate as Tofa, namely language shift to Russian. It is possible to imagine that within the next 100 years, this language hotspot will cease to exist as such, and Russian will be the only language of Siberia.