Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) (54 page)

Read Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) Online

Authors: Jonathan Herring,Sandy Allgeier,Richard Templar,Samuel Barondes

Tags: #Self-Help, #General, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

The combination of words and phrases is, of course, critical. There are other people who are needy but who are neither carnal nor womanizers. Some of them may also have remarkable sonar but without being messy or maddening. What makes Klein’s description so recognizable is that, as he points out, all the traits “were of a piece.”

So how did Klein do it? Was he intuitively asking himself a set of questions that are as obvious to him as the five Ws? Did he leave out anything important? Can we learn a technique to make our own descriptions of people more incisive and complete?

Words from the Dictionary

The development of a simple technique to describe personalities was set in motion in the 1930s by Gordon Allport, a professor of psychology at Harvard. Although Allport was well aware of the uniqueness of each individual, he also knew that scientific fields get started by breaking down complex systems into simple components. Just as understanding the great variety of chemical compounds depended on identifying a limited number of elements, understanding the great variety of personalities may depend on identifying a limited number of critical ingredients. But what exactly are those ingredients?

Allport’s answer was traits: the enduring dispositions to act and think and feel in certain ways that are described by words found in all human languages. Just as chemical elements such as carbon and hydrogen can combine with many others to form endless numbers of complicated substances,

traits such as being outgoing and being reliable can combine with many others to form endless numbers of complicated personalities. But how many traits are there? And how could Allport find out?

To answer this question Allport and his colleague, H.S. Odbert, made a list of the words about personality from

Webster’s New International Dictionary.

2

By analyzing this list, they hoped to identify the essential components of personality that were so obvious to our ancestors that they invented a great many words to describe them. Instead of just concocting an inventory of personality traits out of their own heads, Allport and Odbert would be guided by the cumulative verbal creations of countless minds over countless generations, as recorded in a dictionary.

3

It soon became clear that these researchers had bitten off more than they could chew. The list of words “to distinguish the behavior of one human being from another” had 17,953 entries! Faced with this staggering number, they whittled it down using several criteria. First, they eliminated about a third, such as

attractive,

because the entries were considered evaluative rather than essential: “[W]hen we say a woman is attractive, we are talking not about a disposition ‘inside the skin’ but about her effect on other people.”

4

Another fourth hit the cutting room floor because they describe temporary states of mind, such as

frantic

and

rejoicing,

rather than the enduring dispositions that are defining features of personality traits. Others were thrown out because they were considered ambiguous. In the end, about 4,500 entries met the researchers’ criteria for stable traits.

This doesn’t mean that personality has 4,500 different components; many of the words on the list are easily identifiable as synonyms. For example,

outgoing

and

sociable

are used interchangeably. Furthermore, antonyms, such as

solitary,

describe the same general category of behavior, but at its opposite pole—instead of saying “not sociable” or “not outgoing,” we might say “solitary.” In fact, a wonderful feature of natural language is that it lends itself so well to a graded (or dimensional) description of specific components of personality, from extremely outgoing at one pole to extremely solitary at the other, with modifiers to specify points in between. Put simply, the ancestors who gradually built our language—and all languages—left us with many choices for describing ingredients of personality.

Recognizing that

outgoing

and

solitary

both refer to aspects of an identical trait, how many other words also fit into this category? When I looked up

outgoing

in my thesaurus, I found these synonyms, among others:

gregarious, companionable, convivial, friendly,

and

jovial.

When I looked up

solitary,

I got, among others,

retiring, isolated, lonely, private,

and

friendless.

This tells me that the group of experts who put together this thesaurus decided that all these words belong in a box that can be labeled Outgoing–Solitary. Needless to say, each word in the box may also have some special spin of its own. For example,

solitary, lonely,

and

private

don’t mean exactly the same thing, and writers such as Joe Klein may mull them over to get just the right one. Nevertheless, we all know that these words have a lot in common. To psychologists such as Allport, they all refer to a single overarching trait.

Beyond Synonyms and Antonyms

Does this mean that we can identify the essential building blocks of personality by simply getting a list from a dictionary and then lumping together the synonyms and antonyms from a thesaurus? Can we base a nomenclature of personality on the analysis of professional lexicographers? Or can we use a more open-source approach that pays attention to the ways ordinary people employ words to describe personalities?

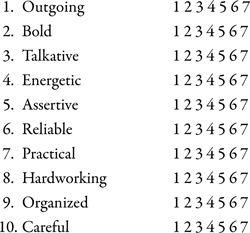

The answer psychologists settled on was both. First, professionals reduced the list to a more manageable number—about a thousand. Then they asked ordinary people to use these words to describe themselves and their acquaintances. To get an idea of the way this was done, please apply the ten words in the following list to someone you know well. In expressing your opinion, use a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 indicating that the person ranks very high, 1 indicating that the person ranks very low, and the other numbers indicating that the person falls somewhere in between.

I have no way of knowing what numbers you selected. But chances are good that they will have a characteristic relationship: The numbers you picked for the first five items probably are similar, and the numbers you picked for the second five items probably are similar. Furthermore, I can say with confidence that most people who give someone a certain score for

outgoing

give them a similar score for

bold, talkative, energetic,

and

assertive;

and that the score they give someone for

reliable

is likely similar to the one they give for

practical, hardworking, organized,

and

careful.

Even though none of the words in each quintet are synonyms, people who are ranked a certain way on one word from each tend to get similar scores on the others. In contrast, people’s scores on the first quintet are independent of their scores on the second quintet. This implies that these non-synonymous words are grouped together in our minds because each refers to some aspect of a related component of personality.

Could any other words be lumped together with

outgoing

or

reliable

to flesh out these two big categories? How many other groupings like this would be discovered if people were asked to make judgments using all the thousand words that the original list was pared down to? And what statistical techniques would be needed to identify these categories? In making the list, Allport set the stage for research on these questions.

5

Bundling Traits

A statistical technique for studying the relationships between these words was invented in the nineteenth century by Francis Galton, a founder of modern research on personality,

whom you’ll read more about later. The technique is used to calculate a correlation coefficient, a number between 1.0 and −1.0 that measures the degree of sameness (positive correlation) or oppositeness (negative correlation). Although Galton invented the technique for other purposes, he also happened to be interested in categorizing the words that we use for personality traits,

6

and he would have been pleased to learn about this application.

To get a feel for this calculation, let’s think about the positive correlations we would find if we asked people to rank someone on

outgoing, sociable,

and

gregarious

by using a scale of 1 to 7. Knowing that these words are synonyms, we would expect to find that if John ranks Mary a 6 on

outgoing,

he likely will rank her around 6 on each of the others. If he then ranks Jane as a 4 on

outgoing,

he likely will rank her around 4 on each of the others. And if Jennifer ranks Jim a 1 on

outgoing,

she likely will rank him around 1 on each of the others. Plugging these scores into Galton’s formula would indicate a great deal of sameness.

Now what sort of correlations would we find between the words in the first non-synonymous quintet (outgoing–bold–talkative–energetic–assertive)? Studies show that these words are correlated strongly, but not as strongly as synonyms, and similar positive correlations are found among the words in the second non-synonymous quintet (reliable–practical–hardworking–organized–careful). In contrast, when we compare the scores for words such as

outgoing

from

the first group with words such as

reliable

from the second group, we don’t find a correlation. This comes as no surprise because we all know that being outgoing and being reliable are not intrinsically related.

Determining the correlations among five or ten words is fairly easy. But determining the correlations among a thousand words was stalled until researchers could turn it over to a computer. To get the raw data, thousands of ordinary people were asked to apply each of these words by ranking their applicability to themselves or another person using a scale of 1 to 7. The mass of data was then analyzed with a more advanced statistical technique, called factor analysis, which measures the correlation between each word and all the others and organizes the correlations into clusters. In this way, some words were identified as highly correlated to each other, making them good representatives of a particular cluster, which psychologists call a domain.

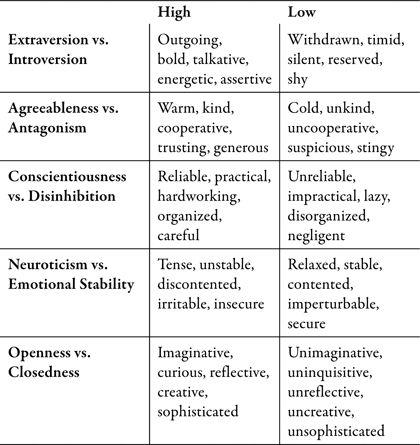

By the early 1980s, the results were in: The words that describe personality traits can be boiled down to just five large domains (see

Table 1.1

), which Lewis Goldberg named the Big Five.

7

Each of them has been given a reasonably descriptive name: Extraversion (E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Neuroticism (N), and Openness (O). If you have trouble recalling these names at first, as I did, you can use the acronyms OCEAN or CANOE to jog your memory until they become second nature.

Table 1.1 The Big Five: Representative Words

Using the Big Five

After the Big Five was discovered, it became the foundation for assessing individual differences in the ways people interact with their social and physical worlds. Three domains—Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism—mainly relate to ways of interacting with other people. The other two—Conscientiousness and Openness—are more general.

8

•

Extraversion is the tendency to actively reach out to others.

People high in Extraversion are stimulated by the social world, like to be the center of attention, and often take charge. They also like excitement and are inclined to be upbeat, fun loving, full of energy, and to experience positive emotions. People low in Extraversion are less interested in interpersonal interactions and tend to be reserved and quiet. But their relative lack of interest in being with people need not indicate that they don’t like them, or that they are socially anxious or depressed; they may just prefer to be alone.