Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) (25 page)

Read Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) Online

Authors: Jonathan Herring,Sandy Allgeier,Richard Templar,Samuel Barondes

Tags: #Self-Help, #General, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

First, start by understanding three simple secrets that can help any of us increase our own personal credibility factor. After you understand these, you can then make the choice to evaluate your own habits and behaviors and seize the opportunity to increase your personal credibility.

Reading for All It’s Worth...

Just reading this book will likely give you some new insights into your daily life experiences and how you personally build or lose credibility as a result of what you do and how you do it. Most of us find, however, that gaining insight doesn’t necessarily get us to the point of taking specific

actions

that can positively change our lives.

Actions

require exactly that—thought, movement, and action on what we learn! As you read—take some action! Pick up your pen or pencil, make notes, underline and highlight anything that speaks to you in a personal way. And, take the small amount of time needed to work through the simple yet important exercises that are provided throughout. You’ll find that the insight you gain will be much deeper and, most important, you’ll move from

learning

more about this topic to

doing

what it takes to enhance your own personal credibility.

Chapter One. Secret #1: Forget Power, Position, Status, and Other Such Nonsense

Strong personal credibility is available for everyone

—regardless of who you are and what you do. Your position, status, or role in life have nothing to do with your personal credibility factor. Different people play different roles in their careers, jobs, and other activities—and some are roles of very high authority—however, there’s no lasting connection between higher status/power and personal credibility. Let’s look at a few examples.

Same Ideas, But Very Different Results

“John” held a senior vice president position in a large Fortune 500 organization. John was a creative, likable, and bright executive. His staff and peers greatly enjoyed working with him and he inspired others to new and creative ways of thinking. As a member of the senior leadership team, John regularly presented suggestions, recommendations, and proposals for consideration with his fellow senior leaders. Unfortunately, the outcome of most of those recommendations was, “Uh, good idea, John. But we can’t implement that idea right now. Maybe we can reconsider later.” He was politely listened to and verbally patted on the head. John just did not have a good track record for gaining approval for his ideas.

This organization was growing, and as is customary when companies grow quickly, reorganization became necessary. “Alice,” another member of the senior management team, was asked to assume responsibility for a larger role in leadership, and as a result, John, along with two other colleagues, was now to report to Alice in her new role as chief administrative officer. John respected Alice and accepted this restructuring positively.

Then, an odd thing started to happen to John’s ideas and recommendations. Alice reviewed many of them personally and then worked with John and the other senior leaders to reconsider implementing those ideas. In about six weeks, approximately 80 percent of the recommendations John had previously made were funded and approved by the president and the other members of the leadership team. These were the same ideas that did not receive much positive attention previously. Why? Alice had personal credibility. John simply did not have it—or at least at the same level. Although John was liked, he did not have the strong respect of the other leaders. In Alice’s new position, she worked with John to have his ideas reevaluated and considered. Although the authority within John’s position was the same, under Alice’s leadership, the results were very different. You might be

thinking that since Alice now had more authority within her newly established position that she was able to get more accomplished.

Bigger position—greater power, right?

Actually, that had no real impact in this situation. The people on the leadership team who had shot down John’s ideas were the same people who later approved them. Alice held the same “rank” as the rest of the members of this team, no more or less positional power than others who were involved in the decision making. This group of leaders, however, believed that Alice would not make recommendations unless they were solid. They just did not have the same confidence in John. We’ll explore more about the specifics that impacted that later. But, the key point is that results did not occur as a result of the

position

Alice or John were in. Both of their positions had status and authority, but Alice was respected—she had stronger personal credibility. Naturally, John was mystified by Alice’s results and why they differed so much from his own. Why did Alice get more respect from the leadership team? Why did it matter that

she

was recommending the same basic concepts that he had previously and yet she received approval? Eventually, John asked Alice to explain how she was able to gain such different outcomes. At first, Alice wasn’t sure how to respond to John’s question. She needed to spend some time thinking about what she did and how she did it. Eventually, however, she was able to provide John with some very specific feedback about how she had learned to work hard in a few basic areas, and how that work had paid off for her. She realized she had learned to do certain things that would increase her opportunity to gain others’ trust and respect. She also assured John that he could choose to make a few simple changes that could significantly improve his results as well. In later chapters, you will discover more about Alice and what she did—and what John had been doing that was diminishing his success and decreasing his personal credibility with this team.

It’s What You

Do

, Not What You

Say

“Chuck” was a leader in a large call center operation. He was bright, tough-minded, and very strongly opinionated. He spoke with authority, and those working with him had no doubt that he would take action based on that authority. He also had a tendency to be somewhat lazy. It was not unusual to see Chuck reclined at his desk, feet up, reading

The Wall Street Journal

. Chuck met periodically with his leadership team, told them his expectations, and then verbally blasted those whose results were less than expected. The performance of Chuck’s team was pretty strong—for a while. Then, performance began to suffer. His team of leaders slowly but surely were either seeking positions elsewhere or were very busy trying to find ways to keep Chuck’s attention off them. Eventually, Chuck’s business results decreased significantly, and this ended in his being replaced.

“Mitch” replaced Chuck. Mitch was also bright and strongly opinionated. Like Chuck, Mitch told people exactly what he thought and expected. He regularly had informal “floor meetings” where he walked from area to area, brought small groups together, told them what he wanted for the organization, and gave time for them to ask questions and make suggestions. He listened respectfully, considered others’ perspectives, and kept employees informed with information on his future plans. He didn’t attempt to make everyone happy—but he usually explained the reasons for his actions and for decisions he made. Mitch also demonstrated energy and passion for his job and the business. If he wasn’t out on the floor talking with people, he was meeting regularly with individual leaders to brainstorm ideas for improvement. Not surprisingly, it was fairly common to hear employees in the organization speak about the difference in leadership styles between Chuck and Mitch. Interestingly, the terms “say” and “do” were used to describe both leaders. Chuck was often referred to as “Mr. Do as I Say, Not as I Do.” The managers who reported to him

often rolled their eyes when leaving conversations with Chuck, incredulous with how he spent his time reading the newspaper while at the same time verbally assaulting them for failing to give enough effort to achieve better results. Mitch, by contrast, was referred to as a leader who would not ask anyone to do anything he wasn’t willing to do first. Employees knew where both leaders stood on issues. They also learned that only one of the leaders, Mitch, was willing to stand in the same place he was asking others to stand. As a result, Mitch was able to gain employees’ willingness to accept and trust his direction.

The organization under Mitch’s leadership began to show more positive results. The business improved. The parent company decided to use this location as a testing ground for new products and processes. Think about it...Chuck and Mitch had the same degree of “position authority.” These two people held the same job with the same power within the position. The results were very different—but it wasn’t the power or authority of the

role

that made the difference! The difference was in how they behaved—and as a result, Mitch gained respect, whereas Chuck lost it.

Secret #1 Applies to Other Life Experiences

We just reviewed two business leadership examples. But what about comparing status or position in our personal lives? We see examples of it every day—with parents, teachers, or even staff at our local coffee shops. The Starbucks barista has less authority within his/her position than the store manager. If you occasionally visit coffee shops, you understand that after you are known as a “regular,” you are hoping to interact with the person who connects with you, remembers your favorite drink in the morning—versus the afternoon—and makes some type of comment that makes you feel recognized or special. You are not at all concerned about whether you are dealing with the manager—you just want to interact with the person who has proven credibility and who you trust to know your preferences! The real power is the positive impact this person leaves as you walk or drive away!

School principals have more authority within their organizations than teachers. When it comes to your kids and how they are performing in school, do you think first about the highest authority position to deal with, or do you think about talking with the individual teacher who is interacting with your child? Typically, the person you want to talk with is the person who has the greatest influence on your child’s situation—the teacher!

Power and authority are not the issue!

Credibility in Parenting

“Charles” and “Linda” are the parents of two young children. They’re a typical young family; both parents work, with precious little time to themselves and with the demands of a four- and two-year-old, plus balancing the rest of their hectic lives—they can feel pretty stressed at times. Occasionally, they lose patience with their kids, and occasionally, they give in to the demands those kiddos place upon them. Generally, though, they treat parenting as their top priority. They make mistakes, like we all do. But, they send very strong messages to their children that they are loved, and that they as parents will set the rules and boundaries for their lives on a daily, consistent basis. Their children are delightful to be around.

“Susan” and “Steve” are also parents. Their children have been raised in very similar circumstances regarding schedules, working parents, and so on. Unfortunately, though, Susan and Steve have raised their children as an afterthought. It’s sad, but in reality, it is true. They were not ready to take on the responsibility of raising kids.

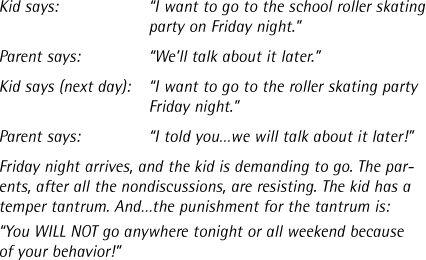

A typical day in the lives of Susan, Steve, and their kids goes something like this:

No one enjoys being around Susan and Steve with their children. It is always a scene of loud disagreement, and the children are becoming sulkier and more difficult in general.

The difference here? Personal credibility. Charles and Linda have established it with their children. Their kids are learning that their parents will behave in a certain way that they can rely on and trust. Susan and Steve have lost credibility and, unfortunately, don’t even realize it. Their children don’t know if they will be ignored, punished, or even indulged because their parents don’t want to deal with the pressure the kids place on them. Steve and Susan just know they are extremely stressed and have children who are likely to have meltdowns. The status or power of being a parent doesn’t mean anything—both sets of parents have the power of the position of parent—it is the parents’ credibility (or lack of it) that leaves the impact on children and others.