Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) (55 page)

Read Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) Online

Authors: Jonathan Herring,Sandy Allgeier,Richard Templar,Samuel Barondes

Tags: #Self-Help, #General, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

•

Agreeableness is the tendency to be altruistic, cooperative, and good-natured.

People high in Agreeableness are considerate, compassionate, helpful, and willing to compromise. They truly like people and assume that everyone is decent and trustworthy. People low on Agreeableness are more self-interested than altruistic, more competitive than cooperative, and likely to be skeptical of others’ intentions. They also tend to be cold, antagonistic, and disrespectful of the rights of others.

•

Conscientiousness is the tendency to control impulses and to tenaciously pursue goals.

People high in Conscientiousness are orderly, reliable, hardworking, neat, and punctual. They tend to plan ahead and think things through. They are more interested in long-term than short-term goals. People low in Conscientiousness are more spontaneous, less constrained, less dutiful, and less achievement-oriented. Although

Conscientiousness shows up prominently in the performance of tasks, it also influences interpersonal relationships.

•

Neuroticism is the tendency to have negative feelings, particularly in reaction to perceived social threats.

People high in Neuroticism are emotionally unstable, tend to be upset by minor threats or frustrations, and are often in a bad mood. They are prone to anxiety, depression, embarrassment, self-doubt, self-consciousness, anger, and guilt. People low on Neuroticism are emotionally stable, calm, composed, and unflappable. But their freedom from negative feelings does not imply that they are particularly inclined to have positive feelings.

•

Openness is the tendency to be imaginative and to enjoy novelty and variety.

People who are high in Openness tend to be artistic, nonconforming, intellectual, aware of their feelings, and comfortable with new ideas. People low in Openness prefer the simple, straightforward, familiar, and obvious to the complex, ambiguous, novel, and subtle. They tend to be conventional, conservative, and resistant to change. Although people who are high on Openness enjoy the life of the mind, Openness is not identical with intelligence. Highly intelligent people can be high or low on O.

After you’ve mulled over the broad meanings of these five domains, you can get a better sense of them by applying them to someone you know. You might start by asking yourself how outgoing, good-natured, reliable, moody, and

creative that person is compared with others. In doing this, you will notice that the person’s relative rankings vary somewhat depending on the situation.

9

For example, a person may be outgoing with friends but shy with strangers, so you have to decide on the average scores by summing up the many observations you’ve made.

10

From this, you will come away with a profile of the person’s basic tendencies, such as moderately extraverted, very agreeable and conscientious, a little neurotic, and very open. Although this is no more than a rough summary of how you regard this person, the Big Five framework will have helped you put your intuitive assessments into words. You will then be in a position to more thoughtfully compare this person with others by seeing his or her differences more clearly.

11

Big Five 2.0

Having made such assessments, you may find that your ideas about each category are still fuzzy. To sharpen your appraisal of a person’s profile of traits, it helps to move from a holistic impression to a more meticulous examination. To do this, you need to learn more about the details of the Big Five.

Paul Costa and Robert McCrae have done the most to clarify these details. Working together at the National Institutes of Health in the 1980s, they developed a questionnaire called the NEO-PI R, which uses phrases rather than adjectives.

12

The big advantage of using phrases is that you can design them to eliminate some of the ambiguity that is inherent in single words. For example, in place of the word

insecure,

a component of Neuroticism, Costa and McCrae

use phrases that spell out certain aspects, such as: “In dealing with people, I always dread making a social blunder” and “I often feel helpless and want someone else to solve my problems.”

13

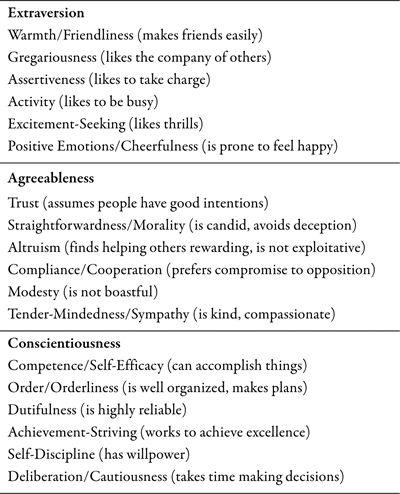

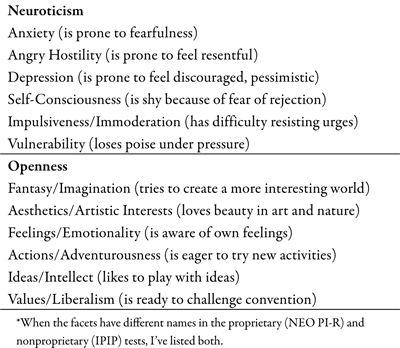

Another reason for the popularity of the NEO-PI R is that it sharpens the assessment of each of the Big Five by subdividing them into six components, called facets. This ensures a more complete evaluation and helps focus attention on specific individual differences. Consider for example, these phrases that assess facets of Extraversion:

• I find it easy to smile and be outgoing with strangers. (Warmth/Friendliness)

• I enjoy parties with lots of people. (Gregariousness)

• I am dominant, forceful, and assertive. (Assertiveness)

• My life is fast-paced. (Activity)

• I love the excitement of roller coasters. (Excitement-Seeking)

• I am a cheerful, high-spirited person. (Positive Emotions/Cheerfulness)

The advantage of using these facets is that it may help you make distinctions that you might have glossed over. For example, many people with an average E score are not average across the board. Some may be somewhat higher on warmth, gregariousness, and positive emotions than on assertiveness, activity, and excitement-seeking; others may have a different balance of tendencies. The same is true for the other major

traits. In each case, you should pay particular attention to facets that stand out as clearly higher or lower than average. Because the whole point of the exercise is to compare people with each other, you’re really looking for these distinguishing characteristics. You may also take note of particular situations in which these distinguishing characteristics are expressed.

To get a feel for the facets of the Big Five, I encourage you to take a free computer-based personality test that resembles the proprietary one devised by Costa and McCrea, at

www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/j/5/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm

. Developed by a group of distinguished personality researchers

14

and overseen by John A. Johnson

15

at Pennsylvania State University, it uses different names for some of the facets but covers similar ground. This free test, called the IPIP, can be taken anonymously in about 20 minutes. If you take it, you will receive an automated e-mail report that shows your relative rankings on the Big Five and its facets by comparing your scores with those of the hundreds of thousands of other people who have already taken it.

To gain more experience with the facets of the Big Five (

Table 1.2

), you may also use the online questionnaire to assess a person you know. Scoring the person on this list of items not only will sharpen your view of him or her. It will also increase your familiarity with this technique. As you become more familiar with the Big Five, you will learn to make such judgments in your head without relying on a questionnaire.

Table 1.2 Facets of the Big Five*

Rethinking Bill Clinton

Another way to get a feel for the Big Five and its facets is to keep it in mind while re-examining the paragraph from Joe Klein’s book that I cited at the start of this chapter. Klein tells us much more about Clinton’s personality than he packed into this paragraph. But for our purpose, I mainly stick to those 165 words:

There was a physical, almost carnal, quality to his public appearances. He embraced audiences and was aroused by them in turn. His sonar was remarkable in retail political situations. He seemed able to sense what audiences needed and deliver it to them—trimming his pitch here, emphasizing different priorities there, always aiming to please. This was one of his most effective, and maddening qualities in private meetings as well: He always grabbed on to some point of agreement, while steering the conversation away from larger points of disagreement—leaving his seducee with the distinct impression

that they were in total harmony about everything. ... There was a needy, high cholesterol quality to it all; the public seemed enthralled by his vast, messy humanity. Try as he might to keep in shape, jogging for miles with his pale thighs jiggling, he still tended to a raw fleshiness. He was famously addicted to junk food. He had a reputation as a womanizer. All of these were of a piece.

As we noted before, Klein built his description by calling attention to a few key traits. But now we can translate the information that Klein provides into the language of the Big Five. Needless to say, much more is known about Clinton, and other observers have painted a somewhat different picture than Klein did.

16

But let’s stick with the paragraph and some other information from his book to illustrate how the Big Five and its facets can help us organize our thoughts about Clinton’s basic tendencies. To do this, I will concentrate on facets in which his scores are notably high or low.

Starting with Extraversion is particularly fitting when considering Clinton because he loves to be the center of attention. Klein emphasizes this with evocative terms for his public appearances, such as “embraced audiences” and “aroused by them,” which translate into very high scores on gregariousness. Clinton is also obviously high on assertiveness, which led him to the most powerful leadership roles, and “womanizer” can be considered partly a reflection of high excitement-seeking. From this and everything else Klein tells us, Clinton ranks high on all facets of Extraversion, and his overall score is at the top of the chart.

Klein also gives us some information about Agreeableness, but Clinton’s score isn’t quite so obvious. From the paragraph, you may first get the impression that he ranks high on A because he is “always aiming to please.” But as you read on, you will realize that he’s just telling his “seducees” whatever they want to hear. In the course of his book, Klein gives many other examples of Clinton’s deceptiveness, which gives him a low score on straightforwardness. Klein also presents evidence that Clinton’s womanizing is exploitative, which lowers his score on altruism and sympathy. When taken together Clinton’s Agreeableness, which appears very high on first meeting him, is lower than it seems.

The information we get about Conscientiousness is limited but revealing. The part about jogging indicates an effort at self-discipline. But this impression is tempered by “try as he might to keep in shape,” “raw fleshiness,” “addicted to junk food,” and “womanizer,” which are hardly testimony to high C. So even though Klein’s paragraph leaves out Clinton’s very high achievement-striving, the lower scores for dutifulness, cautiousness, and deliberation that he documents in other parts of the book combine to give a lower than average ranking on Conscientiousness.

Klein’s paragraph tells us little about Neuroticism except for a hint about “messy humanity.” Other sections of the book tell us that Clinton can get very angry and out of control, but there’s no reason to think of him as being especially prone to negative emotions. In fact, he is unusually capable of brushing off criticism that would make most of us crumble, and he can be cool under extreme fire. When taken together Clinton ranks below average on Neuroticism.

Openness to experience is also not explicitly considered. This omission is not unusual in brief descriptions of people, even though it may turn out to be a distinguishing feature of their personalities. But Klein makes up for this in the rest of the book by providing us with persuasive evidence that Clinton ranks high on most facets of O.

Of course, much about Clinton doesn’t show up in this Big Five profile. But to illustrate the usefulness of this way of describing him, let’s compare it with a similar assessment of another president, Barack Obama, as a way of thinking about their differences. Although Obama has not been in the public eye as long as Clinton, we have already learned a great deal about him from seeing him in action. His two autobiographies fill in many blanks.

17