Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (112 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

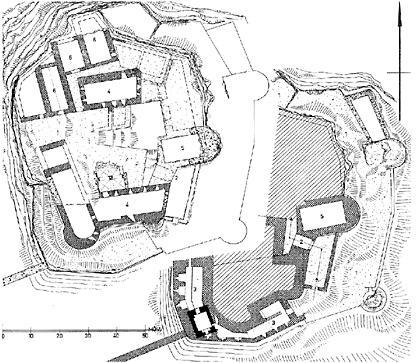

Figure 4.54

Baghrās, core of the Templar fortress

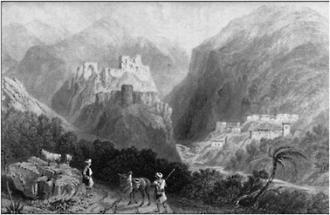

Figure 4.55

Baghrās, lower and upper defences along the eastern side. Note the round tower in the front

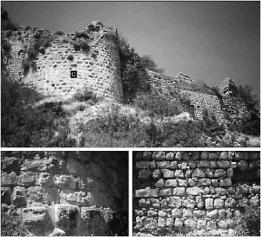

Figure 4.56

Baghrās, the Mamluk tower (C). Note the masonry of the tower wall, and the loose construction of the curtain wall (lower right)

of Armenian construction, identified by Edwards and Sinclair, along the southeast. According to Sinclair the outer galleries were probably built by the Armenians.

Ibn-Shaddād, who describes the site, does not mention any reconstruction carried out by Baybars.

298

Though the sources are mute, there is evidence of Mamluk building. The scale of construction is small and it may have gone unnoticed.

299

The Mamluk approach to Baghrās is a good example of their economical attitude towards military architecture in the rural and frontier areas. Where it was necessary they spared no expense though where one could do without, funds were carefully used and costs were kept low.

The tower in the east (C), encased in a new shell, presents some traits that can be identified as Mamluk work (

Figure 4.56

). The most striking feature is the quality of construction and the relatively well-cut stone. This is particularly striking when compared to the curtain walls. Sinclair suggested that the Mamluk work was executed by Armenian masons. Edwards tends to agree and dates the work on this tower to the reign of Qalāwūn.

300

It is not of the highest Mamluk standard but in this remote

part of the Sultanate it looks distinctly Mamluk and when compared to the work at it is most pleasing to the eye. The upper section of the tower has not survived. The curtain walls were left as they were and no attempt was made to improve them by widening or re-facing them. The only other evidence of Mamluk work is the conversion of the chapel, hidden in the center of the fortress, into a mosque.

it is most pleasing to the eye. The upper section of the tower has not survived. The curtain walls were left as they were and no attempt was made to improve them by widening or re-facing them. The only other evidence of Mamluk work is the conversion of the chapel, hidden in the center of the fortress, into a mosque.

301

Mamluk fortresses: an overview

Mamluk military architecture skipped and jumped pass the stage of trial and error and quickly developed a style and technique that could match the finest Frankish fortresses. It is, however, important to remember that the Mamluk volume of work cannot be compared to that of the Ayyubids, the Franks or the Armenians. In contrast to the Mamluks’ grand public and religious buildings, their fortresses were repaired, rebuilt and renewed but seldom enlarged and never constructed from the foundations.

When examining the details of Mamluk work it is difficult to find a common denominator that would make the eight fortresses discussed here into a homogeneous architectural group. A certain concept can be seen and followed in all the sites covered by this study, but the work itself varies according to regional building materials, local traditions, and the administrative importance attributed to each site. Rather surprisingly, there appears to have been a hierarchy in the level and scale of construction that has no direct connection with the military and defensive role of the fortress.

In certain cases the quality of work evidently depended on the rank and status of the amir who commanded the fortress. The latter argument can be best seen at , which was neither a frontier fortress nor a large administrative center, and yet it displays some of the finest Mamluk military architecture. The fact that it belonged to the

, which was neither a frontier fortress nor a large administrative center, and yet it displays some of the finest Mamluk military architecture. The fact that it belonged to the set the highest standard. More resources were allocated to the building and a larger force of skilled craftsmen seems to have been employed. The wok corresponds to the rank of its owner and is perhaps a symbol of his status. However, one cannot strip

set the highest standard. More resources were allocated to the building and a larger force of skilled craftsmen seems to have been employed. The wok corresponds to the rank of its owner and is perhaps a symbol of his status. However, one cannot strip of its military functions, even if they were relatively limited. Located close to Damascus, the Sultanate’s second capital, it held a large garrison that could be called upon in times of emergency.

of its military functions, even if they were relatively limited. Located close to Damascus, the Sultanate’s second capital, it held a large garrison that could be called upon in times of emergency.

The following is a summary of the main architectural characteristics.

Masonry

Masonry is often an important tool for classification and in some cases can be used to determine chronology. Many scholars maintain that Crusader masonry has distinct characteristics;

302

no similar uniformity is apparent in Mamluk masonry. No specific tool-marks are distinctive or unique to Mamluk builders. Some fortresses present an extremely high standard of masonry whereas others, such as Tall and Baghrās, show fairly poor work. The masons at

and Baghrās, show fairly poor work. The masons at may well have been local, using a tradition that resulted in inferior work. The use of a harder type of stone (basalt), in this site possibly affected the quality, although well dressed basalt stones can be seen at the Crusader fortress of Belvoir.

may well have been local, using a tradition that resulted in inferior work. The use of a harder type of stone (basalt), in this site possibly affected the quality, although well dressed basalt stones can be seen at the Crusader fortress of Belvoir.

Gates

While the Ayyubids consistently built two types of main gates: the bent gateway and the gate tower,

303

the Mamluks in most cases made do with existing structures unless they were badly damaged. The multiple gate system at is a good example. It was probably Armenian-built, and was preserved by the Mamluks. This entrance plan is rare in Muslim fortresses and parallels can be found in Frankish and Armenian work.

is a good example. It was probably Armenian-built, and was preserved by the Mamluks. This entrance plan is rare in Muslim fortresses and parallels can be found in Frankish and Armenian work.

304

The only exception I found was at Safad. The gate at Safad, ruined in the course of the Mamluk siege, was built anew and a T-shaped plan was drawn, which I have not encountered elsewhere.