Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (41 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

The

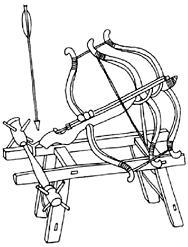

chuang zi nu

was one of the most dominant siege weapons in the Mongolian army during this period. Its construction and operation were complicated and among the Chinese experts recruited by Hülegü were men skilled in the assembly and operation of those giant bows.

60

The structure of this siege machine was similar to that of the crossbow carried by infantry archers. The word

chuang zi nu

means literally “a giant crossbow shaped like a bed.” It was made by using one, two or three giant crossbows connected to each other and mounted on a cart so that the machine could be maneuvered with ease (

Figure 2.4

). The crossbows were constructed from wood and bone, giving them flexibility and strength. The cod was drawn with a winch and the arrows were similar in size to spears and more than one arrow could be fired each time.

61

Figure 2.4

The giant crossbow

A bow of this type was used during Hülegü’s siege of the Assassins’ fortress at Maymundiz.

62

Apart from arrows the size of spears, it fired burning torches that according to Juwaynī caused many casualties.

63

Many parallels can be drawn between the various types of siege machines used in the Middle East and in Northern China. Thee are however a number of important differences, the main one being that all siege machines in China were propelled by manpower (see

Table 2.2

). The iddle East had clearly made an advance, and besides the manually operated siege machines, it was using the counterweight trebuchet, which was more powerful and capable of firing heavier stone projectiles to a greater distance. It also required a considerably smaller team. The ropes pulled by men were replaced by a set of pulleys and a wooden box filled with stones that acted as a weight.

64

The disadvantages of this new siege technology were that its size and weight meant it could not be maneuvered with ease, not even along short distances, and it had to be built and assembled by a professional team of carpenters and engineers.

65

The Chinese on the other hand had the multiple armed siege machines that were not known to the armies of the Middle East even after their encounter with the Mongol army. The size and firepower of those siege machines must have been impressive if one takes into account that each machine could fire between five and seven stones at a time. Thee is also a great difference in the type of projectiles used, since clay catapult balls were unheard of amongst Franks, Ayyubids and Mamluks. Taking into account that a team of forty was needed for the operation of the smallest Chinese siege machine, this may explain the great number of a thousand skilled men that Hülegü recruited from Northern China for his siege units.

The use of incendiaries was common to both iddle Eastern and Northern Chinese armies, though it seems that they were more effective in Chinese and Central Asian warfare since wood, cane, and thatched roofs, all highly inflammable, were widespread building materials. The clay pots known as have been found in a

have been found in a

Table 2.2

The

chuang zi nu

(large mounted crossbows)

Model | Number of men per team | Distance |

Two bows | 4–7 | 243–260m |

Thee bows | 20–30 | 347–520m |

Thee bows | 70 | 347–520m |

Source: Y. Hong, ed., 1 The difference is probably in the type and size of the arrow fired. |

number of archaeological sites on land and at sea though they were more successful in naval warfare where wooden ships and sails could easily catch fire.

66

Apart from the differences in siege machines employed by the armies, there was a vast difference in the way the Northern Chinese siege units in the Mongol army utilized the topography and natural surroundings of the area round a besieged city. This is one of the most impressive characteristics of siege warfare under the Mongol commanders.

Rivers were diverted, dams built and mud ramparts or brick walls were constructed in order to seal the city and cut it off from its surroundings. These large earthen works show an outstanding degree of thought and initiative on the part of well-trained engineering teams and skilled craftsmen, capable of planning and operating such large-scale projects. The rankish, Ayyubid and Mamluk siege teams dug sapping tunnels and worked a variety of different siege machines, but they never attempted to change the course of rivers and/or the area near the besieged city. The main reason was lack of human resources: without a huge labor force such ideas could not be carried out.

There can be no doubt that Eastern Mediterranean siege machines were more advanced. The counterweight trebuchet could hurl stones that weighed 95kg and more to a distance of 300m. On the other hand, the strength of the siege units employed by the Mongols apparently did not depend on superior siege technology or on changing the topography round the besieged city or fortress, but lay rather in the ability to recruit and position mass numbers of siege machines and teams that could run the entire siege operation day and night without halting. The siege of Nishapur (1221) is a good example. The force sent to besiege the city numbered 10,000 men under the command of Toghachar, a son-in-law of Chinggis Khan. The garrison was assisted by the entire population. Juvaini mentions mangonels, naphtha and cross-bows used by the defenders. The city’s defense held for six months. It was only when Tolui arrived in April of 1221 with a significantly larger force that Nishapur was taken. The walls ere breached within three days.

67

Juwaynī describes the effort Tolui’s teams put into gathering stones for the siege machines: “although Nishapur is in a stony region they loaded stones at a distance of several stages and brought them with them. These they piled up in heaps like a harvest, and not a tenth part of them were used.”

68

D’Ohsson and Martin describe the siege machines at Nishapur, giving exact numbers. The Mongols placed 3,000 giant crossbows, 300 stone-hurling siege machines, 700 machines that hurled pots of , 4,000 ladders and 2,500 piles of stones brought from the nearby mountains.

, 4,000 ladders and 2,500 piles of stones brought from the nearby mountains.

69

The assault continued day and night. Assuming this source is reliable, even if the figures are exaggerated they give an idea of the immense strength of the siege contingents that fought in the service of the Mongol armies.

The source of manpower available to the Īlkhānid state differed from that of the Mongol empire.

70

It is rather doubtful that Hülegü’s heirs continued to recruit men from Northern China for their siege contingents. This raises a number of questions concerning the composition, number and origin of the men in the Īlkhānid siege units. The chroniclers provide very little information. On the strength of previous Mongol policy it is more than likely that Muslim engineers were recruited and local siege technology was used along with that brought over from Northern China. But any assumption is bound to remain so for lack of firm evidence. However, it is possible to overcome this obstacle by analyzing the sieges conducted under Hülegü’s command and comparing them to those carried out in later years by his successors. This may enable us to draw some conclusions concerning the development and changes of siege warfare that occurred in the Īlkhānid army.

Sieges conducted by Hülegü while campaigning to the west and after establishing the Īlkhānid state (1256–65)

A survey of the sieges conducted during this period displays a set “Mongol method” composed of a number of stages repeated with very slight variations. Before beginning a siege, Hülegü would send an emissary with a clear message to the governor or the ruler of the city or the fortress; the message conveyed a simple and straightforward offer – surrender and avoid a military confrontation.

71

The next stage was deter mined according to the answer. But in fact the only reply that would prevent a siege was surrender, complete submission and acknowledgment of Mongol sovereignty.

Once it was decided to proceed and besiege the site, the first days were devoted to felling trees, building siege machines, collecting catapult stones, surveying the besieged site, searching for its faults and weaknesses. In addition points to position the siege machines were looked for, so they would gain every advantage of height or a well-protected area that would ensure the teams’ safety. Before the siege of Maymundiz began, Hülegü surveyed the area and examined the fortress gates.

72

He then ordered his best men, chosen from his private guard, to carry logs for the construction of siege machines to the nearby summits that surrounded the fortress. In some sieges the Mongols dug a moat or built a wall or an earth rampart around the besieged city at quite an early stage. During the entire period of organization the army was exposed to the enemy’s attacks and was in a highly vulnerable position. In most cases the besieged force had prepared itself well in advance, and at this early stage it still had plentiful supplies of food, water and weapons; in addition, the morale of the population and garrison was still usually fairly high. Assaults were launched in this phase using both siege machines and small contingents of mounted men who raided the Mongol camp and quickly returned to the safety of the walled city. An example of such behavior can be seen during the siege of Mayyāfarqīn (656/1258–657/1259). At first, the morale at Mayyāfarqīn was high; a number of raids were carried out on the Mongol siege camp, which caused severe losses. But when food supplies became short

and famine began to spread within the city the raids ceased.

73

The siege of ird Kūh (spring 651/1253), carried out by the Mongol vanguard commanded by Ketbugha, began by digging a deep moat and building a high wall round the siege camp. This provided sufficient protection from enemy raids.

74

Meanwhile Ketbugha organized his men round his camp in a pattern known as

järgä,

75

a formation borrowed from the hunting methods used on the plains, but to no avail: the Mongolian forces suffered severe losses, and the fortress remained steadfast. The army eventually retreated and Gird Kūh was taken only eighteen years later during the reign of Abagha.