Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (88 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

The damage caused to the

bāshūra

during the weeks of the siege must have been considerable. Siege machines had been set up on every side of the fortress and sappers

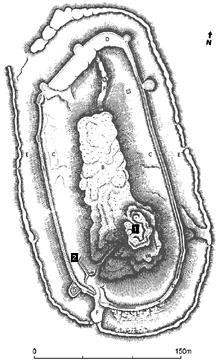

Figure 4.14

The fortress of Safad, the round tower and inner gate

worked day and night. According to Baybars , tunnels were dug under the curtain walls, the towers, the fortress foundations and at the corners.

, tunnels were dug under the curtain walls, the towers, the fortress foundations and at the corners.

105

Although the fortress was surrounded, the Mamluk force focused on the

bāshūra

and this area suffered the most. Ibn Shaddād says that “the fortress had a

bāshūra

that was built by the Franks and when our lord the Sultan ruled it was destroyed to its foundations, and it was built anew from

hirqilī

( ) masonry

) masonry

.

”

106

description minimizes the damage: “He renewed the

description minimizes the damage: “He renewed the

bāshūra

and rebuilt it from

hirqilī

stones and [built] in the same manner the towers and the curtain walls (

badnāt

).”

107

At all events it is clear from both accounts that large parts of the external circuit walls and towers needed repair.

The term

hirqilī

comes from Heraclius, the Byzantine emperor, or Hercules, the mythological hero.

108

The use of the word in this particular context may mean either the re-use of Byzantine stones (possibly from a Byzantine ruin in the near vicinity) or stones of great strength, characteristics attributed to Hercules.

109

The term appears to be quite rare; and is reserved for the description of fortifications. It is used once again by Ibn Shaddād in a description of the Aleppo fortifications built by the Ayyubid prince al-Malik Ghāzī in 611/1213:

Ghāzī in 611/1213:

He tore down the

bāshūra

that used to be in it and poured earth on the tall and rebuilt it with

hirqilī

stones.

110

In this particular context, Ibn Shaddād used the term

hirqilī

to convey the strength and size of the stones used by the Mamluks.

The idea of using large stones may have been inspired by the Mamluks’ contemplation of the results of their own siege. Strengthening the outer fortifications by using larger stones would help endure the impact of heavy siege engines, and make sapping and removing the stone blocks an all but impossible undertaking. The walls were given further protection by a glacis .

.

111

Ibn Shaddād notes that the towers had machicoulis. The shape or number of towers built or repaired is not mentioned in any of the sources.

does not contribute much to our knowledge of the structure of the towers along the external curtain wall. Nevertheless, like

does not contribute much to our knowledge of the structure of the towers along the external curtain wall. Nevertheless, like , he says that those towers were merely repaired rather than built anew from the foundations. No section of the moat or of the towers described by the sources has been excavated, and only fragments can be seen protruding from the earth along the northern side of the site. We thus have no choice but to rely on the literary descriptions. Taking into account the already massive structure of the seven towers built by the Templars (22m in diameter and 48m in height) it seems that the Mamluks only restored the outer circuit of towers and did not add new ones or widen them as they did in

, he says that those towers were merely repaired rather than built anew from the foundations. No section of the moat or of the towers described by the sources has been excavated, and only fragments can be seen protruding from the earth along the northern side of the site. We thus have no choice but to rely on the literary descriptions. Taking into account the already massive structure of the seven towers built by the Templars (22m in diameter and 48m in height) it seems that the Mamluks only restored the outer circuit of towers and did not add new ones or widen them as they did in . The fact that the walls at Safad were almost twice as thick as those at

. The fact that the walls at Safad were almost twice as thick as those at may have been the reason that the Mamluks made do with a relatively small number of towers along the outer wall.

may have been the reason that the Mamluks made do with a relatively small number of towers along the outer wall.