Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (42 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

When a siege camp was eventually organized both sides employed mainly siege machines, and teams were worked night and day. In the siege of Baghdad an iron ram was used, but this was a rather rare instance. One of the most informative narratives of the siege of Baghdad is given by , who in one short sentence describes everything that flew through the sky between the two camps: catapult stones, arrows, spears and javelins.

, who in one short sentence describes everything that flew through the sky between the two camps: catapult stones, arrows, spears and javelins.

76

It seems more than likely that the mounted archers, who were the most dominant force in the Mongol army, dismounted and fired from the ground. This would have increased the number of fighters considerably and provided both a stronger attack and better fire cover for the teams operating the siege machines. On a few occasions the Mongols tried to surround and seal off the city or the fort in order to prevent the population from escaping and food and supplies from entering.

The best example of construction work carried out by the Mongols was probably that used at the siege of Baghdad. After a few weeks of siege the Mongols decided on a change of tactics. This entailed a great investment of time and work, since it included the building of towers that rose above the city walls; once they were completed siege machines were mounted on them, thus gaining the advantage of height. The towers were built of mud bricks, collected from the local town industry, which was positioned outside the city walls. In addition, the water tunnels leading into the city were blocked so that no one could escape.

77

Another example of this tactic of surrounding a besieged city can be seen in the siege of Aleppo in December 657/1259. At the outset of the siege, a large earthen rampart known as a

chappar

was built around the city. While it was being built teams of sappers tried to undermine the foundations of the city wall.

78

When a siege lasted longer than expected, and a city did not show any signs of surrendering, its fortifications remaining solid, the siege was often raised and the army left. In a few cases the Mongols returned and renewed the siege at a later stage. This was done in Arbela (Irbil). The attack commanded y the Mongolian general Uruqtu Noyan took the city, but the citadel remained strong and its garrison refused to surrender. The siege commenced at the end of the winter; the Mongols abandoned the siege and returned in the summer, when the unbearable heat eventually brought about the surrender of the garrison.

79

The fate of a city or a fortress garrison depended on whether the city yielded promptly or resisted and the duration of its resistance. Cities that surrendered were usually spared. Large-scale massacres were carried out in places that refused to submit. In a number of cases the massacres were followed by orders to rebuild the city. After the surrender of Baghdad Hülegü appointed Arab and Persian officials to oversee the reconstruction and administration of the city. In many cases, however, the sacked

cities or strongholds were left in ruins. In some the destruction was so severe, that recovery was long and slow.

80

The impression one is left with is that the majority of the siege teams remained with the core of the Mongolian army under Hülegü’s command, and that they were reserved for cities and strongholds that were strategically important or of great symbolic significance, such as the Assassin strongholds, or Baghdad, the seat of the Caliph,

81

or the fortress of al-Bīra that sat on a ford on the upper part of the Euphrates. Cities and strongholds of secondary importance were besieged by forces recruited from the local population and a small body of siege experts who were probably sent from the main Mongol force.

After Hülegü’s son Yoshmut encountered difficulties during the siege of Mayyāfarqīn he was assisted by the two sons of Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’, the ruler of Mosul. An experienced siege engineer accompanied them. The town eventually fell once its food supplies had been consumed and famine struck the population and garrison.

82

The same combination of local forces and a Mongolian contingent besieged Arbela and Mārdīn.

Those examples leave little doubt that shortly after the Mongols’ arrival in the Middle East they were exposed to siege machines such as the counterweight trebuchet that was in use throughout the region. Hülegü may have recruited local siege experts, as Mongol rulers had done since the reign of Chinggis Khan, but none of the sources explicitly say so. The only information e have is that of the recruitment of a siege expert from among Badr al-Dīn Lu’lu’s men who fought alongside Hülegü’s force in the siege of Mayyāfarqīn.

In contrast to battles waged in the open field the element of surprise was completely absent from the Mongolian sieges. All the various stages were well prepared in advance.

Urban strongholds were occasionally restored by the Mongols. Local commanders were selected to govern places that were strategically important.

83

But on the whole Mongol fighting methods did not depend or rely on fortresses or fortified cities.

84

Unlike the Mamluks, we do not know of fortresses built or reconstructed by the Mongols in Syria or along the Euphrates. Their policy was, moreover, very different from that of the Armenians and the Franks, who based their rule and defense on fortresses and fortified towns. This is best described y Smail: “In the twelfth century, as well as the thirteenth, the walled towns were the ultimate expression of Latin authority in the region.”

85

The idea of a central place,” a fortress or a fortified city that serves as an administrative, financial, religious centre and also provides protection for the local population,

86

was not foreign to the Mongols, but it did not fit their perception of the defense of their own territories.

The Īlkhānid sieges of the fortresses of al-Bīra and

The sieges conducted after the establishment of the Īlkhānid state were mainly carried out against the two frontier fortresses on the Euphrates, al-Bīra and (

(

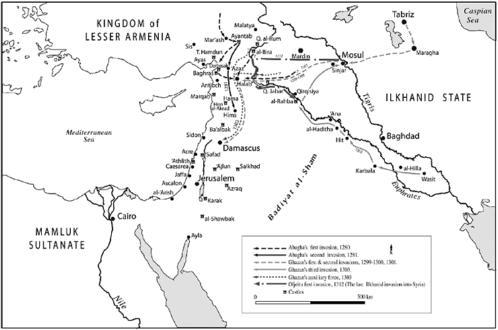

Map 2.2

). The obvious Īlkhānid targets and the constant Mamluk state of alert left little room for surprise attacks. During Hülegü’s reign al-Bīra was besieged twice. While

Map 2.2

Īlkhānid invasion routes into Syria

the first attempt was certainly a success the second was a great failure. This raises some questions as to the siege units and the conduct of the whole affair; the more so since the area and the immediate surroundings of the fortress must have been well known by then to the Īlkhānid army.

Al-Bīra is situated on a natural ford along the northern section of the upper Euphrates,

87

approximately 60 km west of the modern city of Urfa (medieval Edessa). The Mongols considered it as the gate to Syria, and for that same reason it became a key stronghold in the Mamluk defense. The first Mongol siege of al-Bīra was carried out in Dhu al-Hijja 657/December 1259. The garrison fought as best as it could but the Mongol army outnumbered it and the fortress fell within two weeks.

88

Thee years later (659/1262) it was recaptured by al-Barlī (a Mamluk of the late Ayyubid prince ). Baybars rebuilt al-Bīra and granted it special status because of its strategic importance. Although the fortress was well-built, consistently maintained and the garrison reinforced, its ability to withstand the enemy depended on the ability of the Mamluk field army to arrive within days or a couple of weeks at the most.

). Baybars rebuilt al-Bīra and granted it special status because of its strategic importance. Although the fortress was well-built, consistently maintained and the garrison reinforced, its ability to withstand the enemy depended on the ability of the Mamluk field army to arrive within days or a couple of weeks at the most.

89

Al-Bīra was besieged for the second time approximately a month before Hülegü’s death. By the winter of 663/1264–5 the military balance in the region had changed considerably. The Mongol defeat at did not change Mamluk perceptions of the Mongols, but it no doubt broke the Mongol military image of an invincible army. The stability achieed within the Sultanate during the early 1260s allowed Baybars to organize the Mamluk frontier and prepare it for the next Mongol move. The strengthened Mamluk garrison and the well-organized relief forces from the Syrian cities considerably reduced the Īlkhānids’ chances of recapturing the fortress. Between December 1264 and January 1265 the Īlkhānid army erected seventeen siege machines round the fortress of al-Bīra. A section of the moat was filled with wood in order to bring the siege machines closer to the wall.

did not change Mamluk perceptions of the Mongols, but it no doubt broke the Mongol military image of an invincible army. The stability achieed within the Sultanate during the early 1260s allowed Baybars to organize the Mamluk frontier and prepare it for the next Mongol move. The strengthened Mamluk garrison and the well-organized relief forces from the Syrian cities considerably reduced the Īlkhānids’ chances of recapturing the fortress. Between December 1264 and January 1265 the Īlkhānid army erected seventeen siege machines round the fortress of al-Bīra. A section of the moat was filled with wood in order to bring the siege machines closer to the wall.

90

The Mamluk garrison was quick to act and the Mongol operation was foiled by the wood being set on fire.