Paul Revere's Ride (2 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

An important key here is the idea of contingency—not in the sense of chance, but rather of “something that may or may not happen,” as one dictionary defines it. An organizing assumption of this work is that contingency is central to any historical process, and vital to the success of our narrative strategies about the past.

This is not to raise again ill-framed counterfactual questions about what might have happened in the past. It is rather to study historical events as a series of real choices that living people actually made. Only by reconstructing that sort of contingency (in this very particular sense) can we hope to know “what it was like” to have been there; and only through that understanding can we create a narrative tension in the stories we tell about the past.

4

To that end, this inquiry studies the coming of the American Revolution as a series of contingent happenings, shaped by the choices of individual actors within the context of large cultural processes. It centers on two actors in particular. One of them is Paul Revere. Historians have not placed him in the forefront of America’s revolutionary movement. He held no high offices, wrote none of the great papers, joined few of the large deliberative assemblies, commanded no army, and did not advertise his acts. But in another way he was a figure of very high importance. The historical Paul Revere was much more than merely a midnight messenger. He was also an organizer of collective effort in the American Revolution. During the pivotal period from the Fall of 1774 to the Spring of 1775, he had an uncanny genius for being at the center of events. His actions made a difference, most of all in mobilizing the acts of many others. The old Texas canard that remembers Paul Revere as the “Yankee who had to go for help,” when shorn of its pejoratives, is closer to the mark than the mythical image of the solitary rider. His genius was to promote collective action in the cause of freedom—a paradox that lies closer to the heart of the American experience than the legendary historical loners we love to celebrate.

5

The other leading actor in this story is General Thomas Gage, commander in chief of British forces in America and the last Royal

Governor of Massachusetts. General Gage has rarely been remembered with sympathy or respect on either side of the water. He was not a great commander, to say the least. But he was a man of high principle and integrity who personified the British cause in both its strength and weakness. In the disasters that befell him, Thomas Gage was truly a tragic figure, a good and decent man who was undone by his virtues. During the critical years of 1774 and 1775, he also played a larger role than has been recognized by scholars of the American Revolution. It was his advice that shaped the fatal choices of leading British ministers, and his actions that guided the course of American events. Without Thomas Gage there might well have been no Coercive Acts, no midnight ride, and no fighting at Lexington and Concord.

One purpose of this book is to study that series of events as a sequence of choices by Paul Revere, General Gage and many other leaders. Another purpose is to look again at the cultures within which those choices were made. In that respect, Paul Revere’s ride offers a special opportunity. It was part of a larger event, vividly remembered by people who were alive in 1775 as the Lexington Alarm.

Most readers of this book have lived through similar happenings in the 20th century. We tend to remember them with rare clarity. To take the most familiar example, many of us can recollect precisely what we were doing on the afternoon of November 22, 1963, when we learned that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. Many other events in American history have had that strange mnemonic power. This historian is just old enough to share the same sort of memory about an earlier afternoon, on December 7, 1941. More than fifty years afterward, I can still see the dappled sunlight of that warm December afternoon, and still feel the emotions, and hear the words, and recall even trivial details of the place where my family first heard the news of the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor.

It was much the same for Americans who heard the Lexington Alarm in 1775. They also would long remember how that news reached them, and what was happening around them. Many of their recollections were set down on paper immediately after the event. Others were recorded later, or passed down more doubtfully as grandfathers’ tales. These accounts survive in larger numbers than for any other event in early American history. Taken together, they are a window into the world of Paul Revere and Thomas Gage.

When we look through that window, we may see many things. In particular we can observe the cultures that produced these men, and the values that framed their attitudes and acts. From a distance, the principles of Paul Revere and Thomas Gage appear similar to one another, and not very different from those we hold today. Some of the important words they used were superficially the same—words such as “liberty,” “law,” “justice,” and what even General Gage himself celebrated as “the common rights of mankind,”

But when we penetrate the meaning of those words, we discover that the values of Paul Revere and Thomas Gage were in fact very far apart, and profoundly different from our own beliefs. Paul Revere’s idea of liberty was not the same as our modern conception of individual autonomy and personal entitlement. It was not a form of “classical Republicanism,” or “English Opposition Ideology,” or “Lockean Liberalism,” or any of the learned anachronisms that scholars have invented to explain a way of thought that is alien to their own world.

Paul Revere’s ideas of liberty were not primarily learned from books, or framed in terms of what he was against. He believed deeply in New England’s inherited tradition of ordered freedom, which gave heavy weight to collective rights and individual responsibilities—more so than is given by our modern calculus of individual rights and collective responsibilities.

6

In 1775, Paul Revere’s New England notions of ordered freedom were challenged by another libertarian tradition that had recently developed in the English-speaking world—one that was personified in General Thomas Gage. Its conception of liberty was more elitist and hierarchical than those of Paul Revere, but also more open and tolerant, and no less deeply believed. The American Revolution arose from a collision of libertarian systems. The conflict between them led to a new birth of freedom that would be more open and expansive than either had been, or wished it to be. To explore the cultural dimensions of that struggle is another purpose of this book.

We shall begin by meeting our two protagonists, Paul Revere and Thomas Gage. Then we shall follow them through eight months from September 1, 1774, to April 19, 1775—the period of the powder alarms, the Concord mission, the midnight ride, the march of the Regulars, the muster of the Massachusetts farmers, the climactic battles of Lexington and Concord, and the bloody aftermath.

To reconstruct that sequence of happenings, the best and only instrument is narrative. Whatever one might think of Paul Revere’s ride as myth and symbol, most people will agree it is a wonderful story. Edmund Morgan observes that the midnight ride is one of the rare historical events that respect the Aristotelian unities of time and place and action. For dramatic intensity few fictional contrivances can hope to match it.

This book seeks to tell that story. Its purpose is to return to the primary sources, to study what actually happened, to put Paul Revere on his horse again, to take the midnight ride seriously as an historical event, to suspend fashionable attitudes of disbelief toward an authentic American hero, and to move beyond the prevailing posture of contempt for a major British leader. Most of all, it is to study both Paul Revere and Thomas Gage with sympathy and genuine respect.

To do those things is to discover that we have much to learn from these half-remembered men—a set of truths that our generation has lost or forgotten. In their different ways, they knew that to be free is to choose. The history of a free people is a history of hard choices. In that respect, when Paul Revere alarmed the Massachusetts countryside, he was carrying a message for us.

Paul Revere’s Ride

Paul Revere

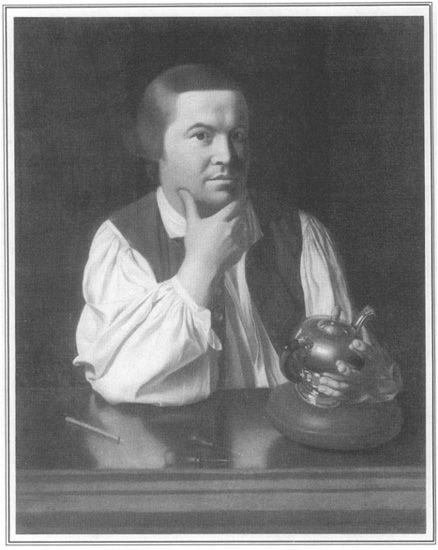

A portrait by John Singleton Copley, circa 1770 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The Patriot Rider’s Road to Revolution

The Patriot Rider’s Road to Revolution

Town born! Turn out!

—Boston street cry, 1770

IN OUR MIND’S EYE we tend to see Paul Revere at a distance, mounted on horseback, galloping through the dark of night. Often we see him in silhouette. His head is turned away from us, and his features are hidden beneath a large cocked hat. Sometimes even his body is lost in the billowing folds of an old fashioned riding coat. The image is familiar, but strangely indistinct.

Those who actually knew Paul Revere remembered him in a very different way, as a distinctive individual of strong character and vibrant personality. We might meet the man of their acquaintance in a portrait by his fellow townsman John Singleton Copley. The canvas introduces us to Paul Revere at about the age of thirty-five,

circa

1770. The painter has caught him in an unbuttoned moment, sitting in his shirtsleeves, concentrating on his work. Scattered before him are the specialized tools of an 18th-century silversmith: two etching burins, a steel engraving needle, and a hammering pillow beneath his arm. With one hand he holds an unfinished silver teapot of elegant proportions. With the other he rubs his chin as he contemplates the completion of his work.

The portrait is the image of an artisan, but no ordinary artisan. His shirt is plain and simple, but it is handsomely cut from fine linen. His open vest is relaxed and practical, but it is tailored in bottle-green velvet and its buttons are solid gold. His work table is functional and unadorned, but its top is walnut or perhaps mahogany,

and it is polished to a mirror finish. He is a mechanic in the 18th-century sense of a man who makes things with his hands, but no ordinary things. From raw lumps of metal he creates immortal works of art.

The man himself is of middling height, neither tall nor short. He is strong and stocky, with broad shoulders, a thick neck, muscular arms and powerful wrists. In his middle thirties, he is beginning to put on weight. The face is round and fleshy, but there is a sense of seriousness in his high forehead and strength in his prominent chin. His dark hair is neatly dressed in the austere, old-fashioned style that gave his English Puritan ancestors the name of Roundheads, but his features have a sensual air that calls to mind his French forebears. The eyes are deep chestnut brown, and their high-arched brows give the face a permanently quizzical expression. The gaze is clear and very direct. It is the searching look of an intelligent observer who sees much and misses little; the steady look of an independent man.

On its surface the painting creates an image of simplicity. But as we begin to study it, the surfaces turn into mirrors and what seems at first sight to be a simple likeness becomes a reflective composition of surprising complexity. The polished table picks up the image of the workman. The gleaming teapot mirrors the gifted fingers that made it. We look more closely, and discover that the silver bowl reflects a bright rectangular window that opens outward on the town of Boston. The artisan looks distantly toward that window and his community in a “reflective” mood, even as he himself is reflected in his work. As we stand before the painting, its glossy surface begins to reflect us as well. It throws back at us the lights and shadows of our own world.

To learn more about Paul Revere is to discover that the artist has brilliantly captured his subject in that complex web of reflections. This 18th-century Boston silversmith was very much a product of his time and place. For all of his Huguenot origins, Paul Revere was a New England Yankee to the very bottom of his Boston riding boots. If we can see him in Copley’s painting, we can also hear him speak in the eccentric way he spelled his words. His spelling tells us that Paul Revere talked with a harsh, nasal New England twang. His strong Yankee accent derived from a family of East Anglian dialects that came to Boston in the 17th century, and can still be faintly heard today.