Paul Revere's Ride (3 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

When Paul Revere’s friends wrote in defense of their cherished charter rights, they spelled “charter” as

chattaer,

with two

t’s

and one

r,

and probably pronounced it with no

r

at all. All his life Paul Revere spelled “get” as

git.

His mother’s maiden name of Hitchborn was written

Hitchbon

in the town of Boston, which was pronounced

Bast’n.

His friends wrote

mash

for “marsh” and

want

for “weren’t,”

hull

for “whole” and

foller

for “follow,”

sarve

for “serve” and

acummin

for “coming.” They favored biblical cadences such as

“we there abode”

and homely expressions such as

“something wet and misty.”

This was the folk-speech of an Anglo-American culture that was already six generations old by 1775, and deeply rooted in Paul Revere’s New England.

1

But in another way, the provincial ring of Paul Revere’s Yankee speech could mislead us. Just as in the surfaces and subtle depths of Copley’s painting, there was more to this man than met the ear. His simple New England twang belied a remarkable complexity of character and culture—the complexity of the nation that he helped to create. Paul Revere was half French and half English, and always entirely American. He was second-generation American on one side, and old-stock American on the other, and cherished both beginnings. He was the product of a Puritan City on a Hill and a lusty, brawling Atlantic seaport, both in the same American town. He thought of himself as an artisan and a gentleman without the slightest sense of contradiction—a new American attitude toward class. He was a man on the make, consumed with personal ambition; and yet he was devoted to his community. He believed passionately in the rule of law, but he assaulted his own kinsman, and did not hesitate to take the law into his own hands. He helped to start a revolution, but his purpose was to resist change and to preserve the values of the past. He was Tocqueville’s American archetype, the “venturous conservative,” consumed with restless energy and much attracted to risk, but never questioning the great ideas in which he always believed. His ideas were a classic example of what Gunnar Myrdal has called the American creed: “conservative in fundamental principles … but the principles conserved are liberal, and some, indeed, are radical.”

His temperament was as American as his ideas. Like many of his countrymen he was a moralist and also something of a hedonist—a man who sought the path of virtue but enjoyed the pleasures of the world. He suffered deeply from the slings of fortune, and yet he remained an incurable American optimist, even an optimistic fatalist. His complex identities were a source of happiness and fulfillment to him—not of frustration or despair.

Paul Revere was many things and one thing, quintessentialy American.

The story of this American life begins 3000 miles away, on the small island of Guernsey in the English Channel. The year was 1715. Peace had recently returned to Europe after a long war, and the sea lanes were open again. On the isle of Guernsey, a small French lad named Apollos Rivoire, twelve years old, was taken by his uncle to the harbor of St. Peter Port. He was put aboard a ship, and sent alone to make his fortune in America.

Like so many immigrants who came before and after him, this child was a religious refugee. He was from a family of French Huguenots, and had been born in the parish of Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, thirty-eight miles east of Bordeaux in the valley of the Gironde. That region had been a hotbed of French Calvinism until the cruel Catholic persecutions of Louis XIV. Some of the Calvinist Rivoire family were forcibly converted to the Roman Church. Others fled abroad—among them young Apollos Rivoire, who was sent to his uncle Simon Rivoire in Guernsey, and later bound as an apprentice to an elderly silversmith in Calvinist New England, where many Huguenots were finding sanctuary.

2

Apollos Rivoire sailed to Boston on November 15, 1715, six days before his thirteenth birthday. He entered the shop of a gifted Yankee artisan, and showed a rare talent in his craft. As more of his work has come to light, experts have studied it with growing respect. A small token of his skill is a set of tiny sleeve buttons that survives today in an American museum. Their delicate tactile beauty has a grace and refinement and sensuality that set them apart from the often austere art of Puritan New England. They are among the finest gold work that was done in British America.

3

In 1722, his master died. Apollos Rivoire bought his freedom from the estate for forty pounds, and set himself up as a goldsmith in Boston. It was not easy to get started. At least three times he was in court for debts he could not pay.

4

Another problem was his name, which did not roll easily off Yankee tongues. After it was mangled into Reviere, Reveire, Reverie, and even Rwoire, the young immigrant changed it to Revere, “merely on account that the bumpkins pronounce it easier,” his son later explained. Paul Revere was a self-made name for a self-made man, in the bright new world of British America.

5

Like many another French Huguenot, this young immigrant moved freely among New England Puritans who shared his Calvinist faith. But the two cultures were not the same, as Apollos Rivoire discovered when the first Christmas came. French Huguenots celebrated the joy of Christ’s birth with a sensuous feast that shocked the conscience of New England. Puritans sternly forbade Christmas revels, which they regarded as pagan indulgence, and proscribed even the word Christmas because they believed that every day belonged to Christ. In 1699, Boston magistrate Samuel Sewall reprimanded a townsman for “partaking with the French Church on the 25 [of] December on account of its being Christmas-day, as they abusively call it.”

6

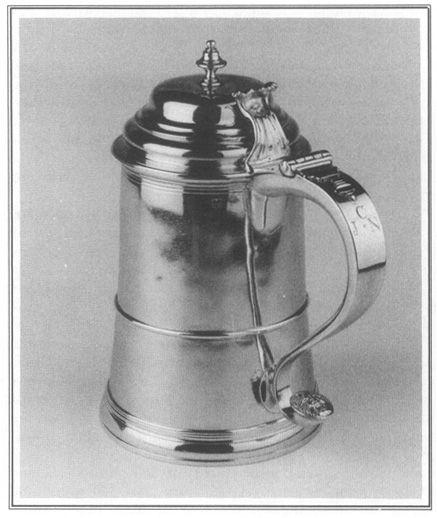

These artifacts testify to the extraordinary skill and creativity of Apollos Rivoire, the father and teacher of Paul Revere. The small sleeve buttons (made circa 1730) are among the finest surviving gold work ever done in British America. Their delicate floral pattern and swirling leaf border are common design motifs of the period, but their deceptively simple shape and proportions are very distinctive, and exceptionally difficult to manufacture. The various elements are brought together in a design that combines vitality and symmetry with high success. In the same manner, the silver tankard above (made by Apollos Rivoire circa 1750) develops the conventional designs of English craftsmanship with a distinctive flair that was unique to its gifted maker. The result is an extraordinary synthesis of refinement and strength. (Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery and the Henry Francis Dupont Winterthur Museum).

Despite these differences, or perhaps because of them, Huguenots and Puritans intermarried at a rapid rate. Of all French weddings in Boston before 1750, no fewer than 88 percent were to an English spouse. One of these mixed marriages was that of Apollos Rivoire. In 1729 he married a Yankee girl named Deborah Hitchborn and became part of her large family, which supplied the other side of Paul Revere’s inheritance.

7

The history of the Boston Hitchborns is a classic American saga. The founder was Deborah’s great-grandfather, David Hitch-born, who came to New England from old Boston in Lincolnshire during the Puritan Great Migration. He appears to have been a servant of humble rank and restless disposition. For some unknown offence, a stern Puritan magistrate sentenced him to wear an iron collar “till the court please, and serve his master.”

8

The second generation of Hitchborns left servitude behind and became their own masters—still very poor, but proud and independent. The third generation were people of modest property and standing; among them was Thomas Hitchborn, proprietor of Hitchborn wharf and owner of a lucrative liquor license that allowed him to sell Yankee rum to seamen and artisans on the waterfront. The fourth generation were solid and respectable Boston burghers; they included Thomas Hitchborn’s daughter Deborah (1704-77), a godfearing Yankee girl who married the gifted Huguenot goldsmith Apollos Rivoire, owned the Puritan Covenant in Boston’s New Brick Church, and raised her children in the old New England way. The fifth generation began with her eldest surviving son, the patriot Paul Revere, who was baptized in Boston on December 22, 1734.

9

Paul Revere grew up among the Hitchborn family—he had no other in America. His playmates were his nine Hitchborn cousins. When the time came to baptize his own children, all were

given Hitchborn family names except the patronymic Paul. He never learned to speak his father’s language. In 1786 he wrote, “I can neither read nor write French, so as to take the proper meaning,” But he cherished the emblems of his French heritage—a silver seal from the old country, a few precious papers, and the stories that his father told him. In a mysterious way, something of the spirit of France entered deep into his soul—a delight in pleasures of the senses, an ebullient passion for life, an

elan

in the way he lived it, and an indefinable air that set him apart from his Yankee neighbors.

10

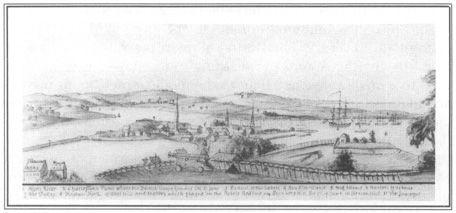

Boston in 1775

A view of the North End from Beacon Hill. The large warship in the harbor is HMS Somerret, and the highest steeple is the Old North Church. Ink and watercolor draning. (Librar) of Congress)

At the same time, he became a Yankee too. His mind and character were shaped by the established institutions of New England—family, school, church, and the town itself. Probably he learned his letters in a kitchen school where ancient Puritan dames kept order with their pudding sticks, and little Yankee children learned to recite the alphabet as if it were a prayer. At about the age of seven, he was sent to Boston’s North Writing School, famous for its stern Calvinist pedagogues who specialized in purging the old Adam from obstreperous youth. Their methods were harsh, but highly effective. Paul Revere gained a discipline of thought without losing his curiosity about the world. His teachers made him a lifelong learner; all his life it was said that he “loved his books.”

11

In a larger sense, the town of Boston became his school, and the waterfront served as his playground. An engraving he later

made of Boston’s North Battery shows three boys splashing in the harbor near his childhood home. One of them might have been young Paul Revere.

12

The Boston of his youth was very different from the city that stands on the same spot today—closer in some ways to a medieval village than to the modern metropolis of steel and glass. In 1735, Boston was a tight little town of 15,000 inhabitants, crowded onto a narrow hill-covered peninsula that sometimes became an island at high tide. From a distance the skyline of the town was dominated by its steeples. Boston had fourteen churches in 1735, all but three of them Calvinist. Despite complaints of spiritual declension by the town’s Congregational ministers, the founding vision of St. Matthew’s “City on a Hill” was still strong a century after its founding. Such was the rigor and austerity of this Puritan community that Samuel Adams called it a “Christian Sparta.”

13