Paul Revere's Ride (4 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

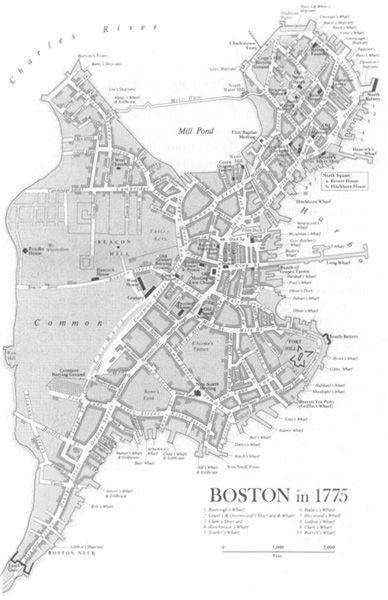

The town was not welcoming to strangers. From the mainland it could be entered only through a narrow gate across the slender isthmus called Boston Neck, or by ferry from Charlestown. On Boston Neck the first structure that greeted a traveler was a large and well-used gallows. In Charlestown, the road to the ferry led past a rusted iron cage that held the rotting bones of Mark, an African slave who had poisoned his master. The slave’s accomplice had been burned at the stake.

But there was also another side of Boston. This City on a Hill was a busy seaport. No part of the town was more than a few blocks from salt water. The housefronts echoed to the cry of oystermen with bags of bivalves on their shoulders, shouting “Oise, buy-ni-oise: here’s oise!” Lobstermen pushed their barrows, “always painted red within and blue without,” calling “Lob, buy Lob!” as they went along the streets.

14

On the waterfront the boys of Boston darted to and fro beneath bowsprits and mooring lines, while fishermen unloaded their catch and artisans toiled at their maritime trades. Seamen in short jackets strolled from one tavern to the next, and prostitutes beckoned from alleys and doorways. “No town of its size could turn out more whores than this town could,” one 18th-century visitor marveled. All this was part of the education of Paul Revere.

15

Inside Boston’s North End where Paul Revere lived most of his life, visitors found themselves in a maze of crooked streets and close-built brick and wooden houses, with weather-blackened clapboards and heavy forbidding doors. The inhabitants were closely related by blood and marriage, intensely suspicious of strangers, and firmly set in their ancestral ways. In time of danger, an ancient cry would ring through the streets: “Town born! Turn out!”

16

Even as a child, Paul Revere entered into Boston habits. Near his house was a handsome brick church, variously called Christ Church, North Church, or the Eight Bell Church, after its carillon of English bells. One bell was inscribed “We are the first ring of bells cast for the British Empire in North America AR Ano 1744.”

17

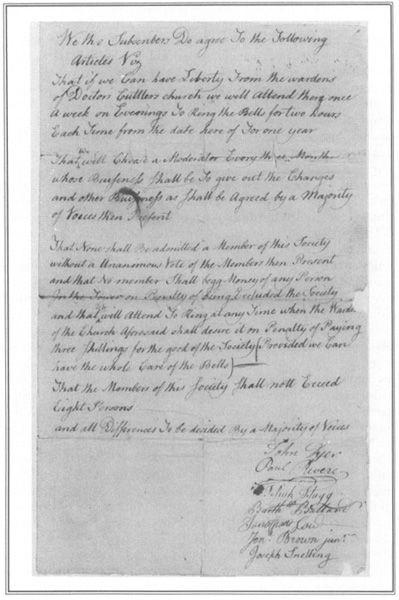

The great bells fascinated the boys of the North End. In their early teens, Paul Revere and his friends founded a bell ringers’ association. They sent a petition to the Rector, proposing that “if we can have liberty from the wardens of Dr. Cuttler’s church, we will attend there once a week on evenings to ring the bells for two hours,”

That document tells us many things about Paul Revere and his road to revolution. These boys of Boston drew up a solemn covenant, and instituted a government among themselves very much like Boston’s town meeting. They agreed that “we will choose a moderator every three months whose business shall be to give out the changes and other business as shall be agreed by a majority of votes then present … all differences to be decided by a majority of voices,” Membership was restricted as narrowly as in a New England church or town. The boys decided that “none shall be admitted a Member of this society without a unanimous vote,” They also covenanted not to demean themselves by Roman Catholic corruptions, and promised to work for their rewards: “No member,” they voted, “shall begg money of any person.”

18

This simple document, drawn up by Boston boys barely in their teens, summarizes many of the founding principles of New England: the sacred covenant and the rule of law, self-government and majority vote, fundamental rights and free association, private responsibility and public duty, the gospel of service and the ethic of work, and a powerful idea of community.

Another of those principles was the doctrine of the calling. Paul Revere was taught that every Christian had two callings—a special calling to work in one’s vocation, and a general calling to do Christ’s work in the world. The great Boston divine Cotton Mather explained this idea in a homely metaphor that would have been instantly clear to any boy who lived near Boston’s waterfront. Getting to Heaven, said Cotton Mather, was like rowing a boat with two oars: pull on one oar alone, and the boat will spin in circles.

All his life, Paul Revere pulled on both oars. He became an apprentice to his father and mastered the special calling of “gold-smith,” working sometimes in that precious metal, but more often in silver, and later in copper and brass as well. When his father died in 1754, Paul Revere took over the business at the age of nineteen and became the main support of his family.

19

He worked hard, survived difficult times, and gradually became affluent, though never rich. He was known in town as a man who knew the value of money. Even his most intimate relationships were cast in terms of cash accounts. He looked faithfully after his widowed mother, but charged her room and board in his own home. This was the custom in Boston, where everyone was expected to pay his way.

20

Bell Ringers’ Agreement, circa 1750 This covenant was signed by seven boys of Boston, including Paul Revere at about the age of fifteen. It is in the possession of the Old North Church.

Paul Revere applied his artisan’s skills to many profitable tasks. He made frames for miniature portraits by John Singleton Copley. He studied the difficult art of copper-plate engraving, and did many illustrations for Boston printers. As a sideline he learned a method of “setting false teeth,” and advertised that “persons so unfortunate as to lose their Fore-Teeth by Accident, and other-ways, to their great detriment not only in looks but speaking may have them replaced with artificial ones … by PAUL REVERE Goldsmith.”

21

But his major employment before the Revolution was as a silversmith. Much of his business in this thrifty Yankee town consisted of mending and repair work. In 1763, he billed Peter Jenkins for “making a fellow to your buckle.” His account books were filled with similar charges for “mending bruises” or patching holes in silver vessels.

22

Many of Boston’s leading Whigs were his customers. He sold a freemason’s medal to James Graham; a new brandy cock to Sam Adams who had worn out his old one; and a bosom pin to the beautiful Mrs. Perez Morton, whose portrait by Gilbert Stuart is one of the glories of American art.

23

At the same time, he also supplied the extravagant tastes of the new Imperial elite. In 1764, he charged Andrew Oliver, Junior, son of Boston’s much hated Imperial Stamp Officer, for “making a sugar dish out of an Ostrich egg.”

24

Paul Revere also made small items of gold, but most of all he was known for his silver. The products of his shop are interesting in many ways, not least for what they reveal about the personality of their maker. His best work was executed to a high standard— the more difficult the piece, the greater the skill that it displayed. But the silver that came from Paul Revere’s shop also showed a highly distinctive pattern of minor flaws. Experts observe that his silver-soldering was not good, his interior finish was sometimes

slovenly, and his engraving was often slightly off-center. Paul Revere was never at his best in matters of routine, and tended to become more than a little careless in tedious and boring operations. But he had a brilliant eye for form, a genius for invention, and a restless energy that expressed itself in the animation of his work. Two centuries later, his pieces are cherished equally for the touchmark of their maker and the vitality of his art.

25

At the same time that Paul Revere worked at his special vocation, he also served his general calling as a Christian and churchgoer, citizen and townsman, husband and father. In August 1757 he married his first wife, Sarah Orne. Little is known about this union. The first baby arrived eight months after the wedding—a common occurrence in mid-18th-century New England, where as many as one-third of the brides in Yankee towns were pregnant on their wedding day. Eight children were born in swift succession.

26

Sarah died in 1773, worn out by her many deliveries. Paul Revere buried her in Boston’s bleak Old Granary Burying Ground beneath a grim old-fashioned Puritan grave marker with a hideous death’s head and crossbones, which were meant to remind survivors of their own mortality.

27

Five months later Paul Revere married Rachel Walker, a lively young woman of good family, eleven years his junior. According to family tradition they met in the street near his shop. It was a love match. Paul Revere wrote poetry to his wife—”the fair one who is closest to my heart,” A draft of one love poem survives incongruously on the back of a bill for “mending a spoon.” Rachel returned his affection. She was a woman of strength and sunny disposition, deeply religious and devoted to her growing family. Eight more children were born of this union, which by all accounts was happy and complete.

28

But in another way this family was deeply troubled. The dark shadow of death loomed constantly over it. Of Paul Revere’s eleven brothers and sisters, five died in childhood and two as young adults. Among his sixteen children, five were buried as infants and five more in early adulthood. He was only nineteen when his father died, and forty-two when he lost his mother. Many of these deaths came suddenly, with shattering force. The children died mostly of “fevers” that struck without warning. Whenever his babies took sick, Paul Revere was overcome by an agony of fear for his “little lambs,” as he called them. Their numbers did not diminish the depth of his anxiety. Even his ebullient spirits were utterly crushed and broken by their death.

29

In Paul Revere’s time, many people suffered in the same way. Their repeated losses gave rise to a fatalism that is entirely foreign to our thoughts. Rachel once wrote to her husband, “Pray keep up your spirits and trust yourself and us in the hands of a good God who will take care of us. Tis all my dependence, for vain is the help of man.”

30

Most people were fatalists in that era, but their fatalism took different forms. The Calvinist creed of New England taught that the “natural man” was impotent in the world, but with God’s Grace he became the instrument of irresistible will and omnipotent force. This paradox of instrumental fatalism was a powerful source of energy and purpose in New England. It also became a spiritual force of profound importance in Paul Revere’s career.

31

On the Puritan Sabbath, he went faithfully to church. All his life Paul Revere belonged to Boston’s New Brick Church, often called the “Cockerel” after the plumed bird that adorned its steeple vane. His children were baptized there, as he himself had been. It was said that he attended church “as regularly as the Sabbath came.”

32

On weekdays he served his community. Like Benjamin Franklin, another Boston-born descendant of Puritan artisans, Paul Revere became highly skilled at the practical art of getting things done. When Boston imported its first streetlights in 1774, Paul Revere was asked to serve on the committee that made the arrangements. When the Boston market required regulation, Paul Revere was appointed its clerk. After the Revolution, in a time of epidemics he was chosen health officer of Boston, and coroner of Suffolk County. When a major fire ravaged the old wooden town, he helped to found the Massachusetts Mutual Fire Insurance Company, and his name was the first to appear on its charter of incorporation. As poverty became a growing problem in the new republic, he called the meeting that organized the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, and was elected its first president. When the community of Boston was shattered by the most sensational murder trial of his generation, Paul Revere was chosen foreman of the jury.

33

With all of these activities he gained a rank that is not easily translated into the conventional language of social stratification. Several of his modern biographers have misunderstood him as a “simple artizan,” which certainly he was not.

34

Paul Revere formed a class identity of high complexity—a new American attitude that did not fit easily into European categories. All his life Paul Revere

associated actively with other artisans and mechanics and was happy to be one of them. When he had his portrait painted by Copley he appeared in the dress of a successful artisan.

35

At the same time he also considered himself a gentleman, and laid claim to an old French coat of arms that was proudly engraved on his bookplates. This was not merely a self-conceit. A commission from the governor in 1756 addressed him as “Paul Revere, Gentleman.” In 1774, Boston’s town meeting also recognized him in the same way. On his midnight ride he dressed as a gentleman, and even his British captors ceremoniously saluted him as one of their own rank, before threatening to blow out his brains. One officer pointed his pistol and said in the manner of one gentleman to another, “May I crave your name, sir?”

36