Paul Revere's Ride (5 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

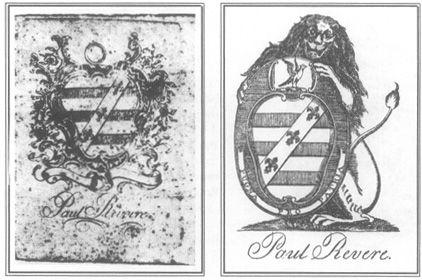

The immigrant Apollos Rivoire changed his name, but kept his French identity, and engraved an elegant coat of arms on his bookplate. His American son Paul Revere thought of himself as both an artisan and a gentleman, and laughed even at his own pretensions—a new American attitude toward class. With self-deprecating humor, he modified the family arms on his bookplate to include a jolly British lion, a jaunty Gallic cock, and the militant American motto,

Pugna pro Patria.

Both bookplates are in the American Antiquarian Society.

Paul Revere’s idea of a gentleman was distinctively American, and very different from its European usage. Once he defined a gentleman as a man who “respects his own credit.” Later in life, when dealing with the trustees of an academy who had failed to pay for one of his bells, Paul Revere wrote scathingly, “Are any of the Trustees Gentlemen, or are they persons who care nothing for character?”

37

The status of a gentleman for Paul Revere was a social rank and a moral condition that could be attained by self-respecting men in any occupation. European writers understood the idea of a “bourgeois gentilhomme” as a contradiction in terms, but in the new world of British America these two ranks comfortably coexisted, and Paul Revere was one of the first to personify their union. In his own mind he was an artisan, a businessman, and a gentleman altogether.

38

In 1773 Paul Revere married Rachel Walker, his second wife. He wrote her love poems on the back of his shop accounts, and in 1784-85 had this miniature painted on ivory, probably by Joseph Dunkerly. It is set in a handsome gold frame that her husband probably made himself. Paul Revere had sixteen children (eight by Rachel) and at least 52 grandchildren. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

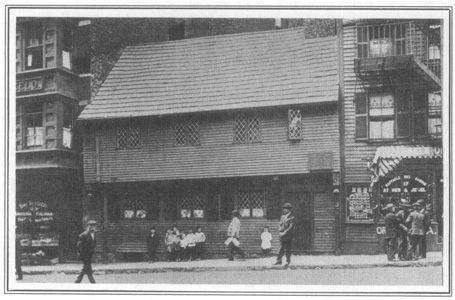

This house stood on Boston’s North Square nearly a century before Paul Revere bought it in 1770. He lived here until 1780, later moving to a three-story brick mansion at Charter and Hanover streets. In the summer, the Revere family kept a country cottage at Cantondale. But always he will be associated mainly with the house where he was living in 1775. This early postcard captures the busy street life of Boston’s North End from Paul Revere’s era to our own time. (Paul Revere Memorial Association)

He was also an associating sort of man. When he died, a newspaper reported that his body was followed to the grave by “troops of friends.” In Boston he had many boon companions. He kept a small boat on the waterfront and a riding horse in his own barn next to his house in Boston, and he liked to fish and shoot, and ride for recreation across the Massachusetts countryside. He knew the inside of many taverns in the town, and enjoyed a game of cards or backgammon, and signed a petition to permit a playhouse in a town that had banned actors for two centuries.

39

Among his many friends, Paul Revere was known for candor and directness, even to a fault. He was in the habit of speaking his mind; and when words failed him, sometimes he used his fists. In 1761, at the age of thirty-six, he came to blows with Thomas Fosdick, a hatter who had married one of Paul Revere’s many Hitchborn cousins. Nobody remembers what the quarrel was about. Something that Thomas Fosdick said or did so infuriated Paul Revere that he attacked his kinsman.

New England did not tolerate that sort of violence. Paul Revere was hauled into Boston’s Court of Common Pleas, where a stern New England judge found him guilty of “assaulting and beating” his kinsman, ordered him to pay a fine, and made him give bond for his good behavior. But the fine was only six shillings, eight pence; and one of Paul Revere’s bondsmen was the brother of the victim. Whatever the facts, both the judge and at least one member of the Fosdick family appear to have felt that Thomas Fosdick got what he deserved. The incident did not lower Paul Revere’s standing in the town.

40

He was a gregarious man, always a great joiner. In 1755 he joined the militia as a lieutenant of artillery, and served in an expedition against Crown Point during the French and Indian War.

41

After he returned in 1760, he became an active Mason, and in 1770 was elected master of his lodge. Freemasonry was deeply important to Paul Revere. All his life he kept its creed of enlightened Christianity, fraternity, harmony, reason, and community

service. Often he was to be found at the Green Dragon Tavern, one of the grandest hostelries in Boston, which his lodge bought for its Masonic Hall.

42

Another of his haunts was a tavern called the Salutation, after its signboard that showed two gentlemen deferring elaborately to one another. Here Paul Revere was invited to join the North Caucus Club, a political organization—one of three in Boston, founded by Sam Adams’s father as a way of controlling the politics of the town. The North Caucus was a gathering of artisans and ship’s captains who exchanged delegates with the other Caucuses and settled on slates of candidates before town meetings.

43

Paul Revere was also invited to join the Long Room Club, which met above a printing shop in Dassett Alley, where Benjamin Edes and John Gill published the

Boston Gazette.

This secret society was an inner sanctum of the Whig movement in Boston—smaller and more select than the North Caucus. Its seventeen members included the most eminent of Boston’s leading Whigs. Most had been to Harvard College. Nearly all were lawyers, physicians, ministers, magistrates, and men of independent means. Paul Revere was the only “mechanic.”

44

The printing shop of Benjamin Edes below the Long Room Club became a favorite meeting place for Boston Whigs. In the Fall of 1772, John Adams happened by Edes’s office. Inside he found James Otis, “his eyes, fishy and fiery and acting wildly as ever he did.” Standing beside him was Paul Revere.

45

Another political rendezvous was a tavern called Cromwell’s Head, whose owner Joshua Brackett was a friend and associate of Paul Revere. Its signboard, which was meant to symbolize the Puritan origins of Boston Whiggery, hung so low over the door that everyone who entered was compelled to bow before the Old Protector. Paul Revere was one of the few men who was comfortable in all of these places. Each of them became an important part of Boston’s revolutionary movement.

46

In 1765, the town of Boston was not flourishing. Its population had scarcely increased in fifty years. Business conditions were poor. Many artisans and merchants fell into debt during this difficult period, including Paul Revere himself, who was temporarily short of cash. In 1765, an attempt was made to attach his property for a debt of ten pounds. He managed to settle out of court, and was lucky to stay afloat in a world depression.

This was the moment when Britain’s Parliament, itself hard pressed, unwisely decided to levy taxes on its colonies. America instantly resisted, and in the summer of 1765 Paul Revere joined a new association that called itself the Sons of Liberty. In the manner of Freemasonry, its members exchanged cryptic signs and passwords, and wore special insignia that might have been made by Paul Revere—a silver medal with a Liberty Tree and the words “Sons of Liberty” engraved on its face.

47

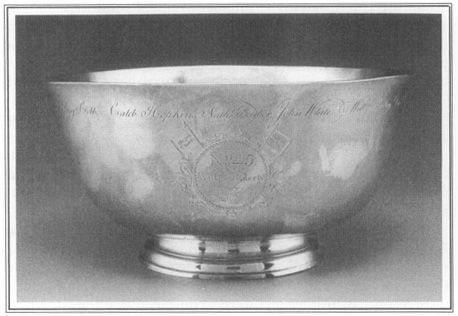

The Sons of Liberty or Rescinders’ Bowl was made by Paul Revere for the subscribers whose names appear around the rim. It commemorated the ninety-two Massachusetts legislators who defied the King’s command to rescind a Circular Letter that summoned all the colonies to resist the Townshend Acts. The bowl is embellished with liberty poles, liberty caps, Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights, and John Wilkes’ polemic, No. 45 North Briton. The inscription condemns “the insolent Menaces of Villains in Power,” (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The Sons of Liberty took a leading part in Boston’s campaign against the Stamp Act. When Parliament at last repealed the hated tax, Paul Revere helped to organize a public celebration on Boston Common. He engraved a design for a large paper obelisk, illuminated by 280 lamps and covered with symbols of liberty and defiance.

48

That moment of triumph was short-lived. In 1767, desperate British ministers tried again to tax America, in a new set of measures called the Townshend Acts. The legislature of Massachusetts responded with a Circular Letter to its sister colonies, urging all to resist as one. British leaders were so outraged that the King himself ordered the Massachusetts Circular Letter to be rescinded. The legislature refused by a vote of 92 to 17. Paul Revere was commissioned by the Sons of Liberty to make a silver punch bowl commemorating the “Glorious 92,” The “Rescinders’ Bowl” became a cherished icon of the American freedom.

49

While the Massachusetts legislature acted and resolved against the Townshend duties, Paul Revere organized resistance in another way. The taxes were to be enforced by new customs officers. Many were corrupt and rapacious placemen. When these hated men appeared in Boston, the Sons of Liberty turned out on moonless nights with blackened faces and white nightcaps pulled low around their heads. More than a few customs commissioners fled for their lives. On one occasion a Boston merchant noted in his diary, “Two commissioners were very much abused yesterday when they came out from the Publick dinner at Concert Hall. … Paul Revere and several others were the principal Actors.”

50