Penny le Couteur & Jay Burreson (6 page)

Read Penny le Couteur & Jay Burreson Online

Authors: Napoleon's Buttons: How 17 Molecules Changed History

Tags: #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #General, #World, #Chemistry, #Popular Works, #History

THE AROMATIC MOLECULES OF CLOVES AND NUTMEG

Although cloves and nutmeg come from different plant families and from remote island groups separated by hundreds of miles of mainly open sea, their distinctively different odors are due to extremely similar molecules. The main component of oil of cloves is eugenol; the fragrant compound in oil of nutmeg is isoeugenol. These two aromatic moleculesâaromatic in both smell and chemical structureâdiffer only in the position of a double bond:

The sole difference in these two compoundsâthe double bond positionâis arrowed.

The similarities between the structures of these two compounds and of zingerone (from ginger) are also obvious. Again the smell of ginger is quite distinctive from that of either cloves or nutmeg.

Zingerone

Plants do not produce these highly scented molecules for our benefit. As they cannot retreat from grazing animals, from sap-sucking and leaf-eating insects, or from fungal infestations, plants protect themselves with chemical warfare involving molecules such as eugenol and isoeugenol, as well as piperine, capsaicin, and zingerone. These are natural pesticidesâvery potent molecules. Humans can consume such compounds in small amounts since the detoxification process that occurs in our livers is very efficient. While a massive dose of a particular compound could theoretically overpower one of the liver's many metabolic pathways, it's reassuring to know that ingesting enough pepper or cloves to do this would be quite difficult.

Even at a distance from a clove tree, the wonderful smell of eugenol is apparent. The compound is found in many parts of the plant, in addition to the dried flower buds that we're familiar with. As long ago as 200 B.C., in the time of the Han dynasty, cloves were used as breath sweeteners for courtiers in the Chinese imperial court. Oil of clove was valued as a powerful antiseptic and a remedy for toothache. It is still sometimes used as a topical anesthetic in dentistry.

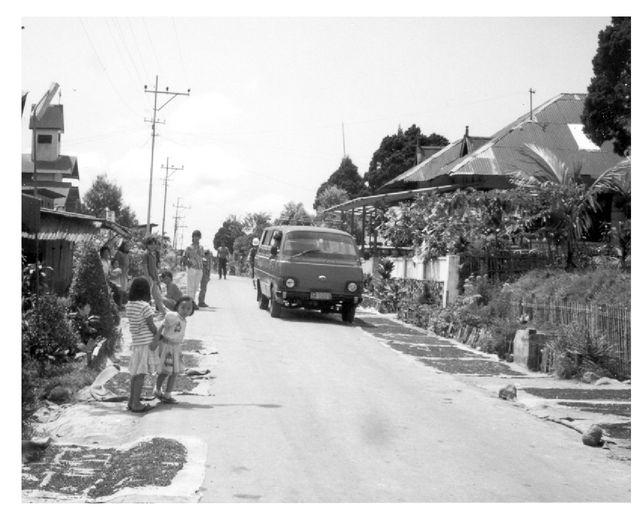

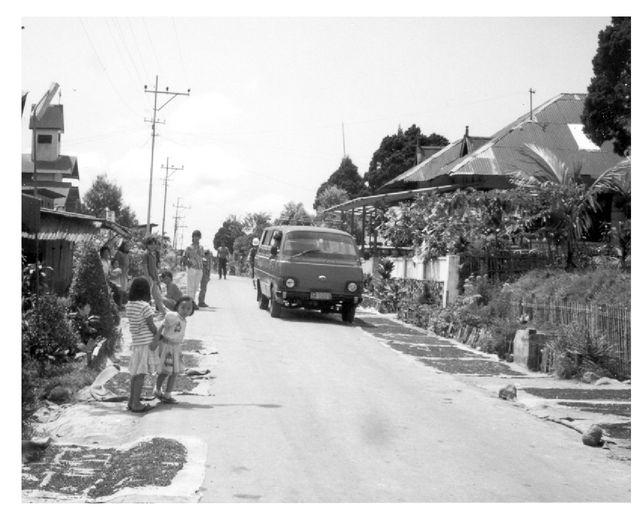

Drying cloves on the street in Northern Sulawesi, Indonesia.

(Photo by Penny Le Couteur)

(Photo by Penny Le Couteur)

The nutmeg spice is one of two produced by the nutmeg tree, the other being mace. Nutmeg is ground from the shiny brown seed, or nut, of the apricotlike fruit, whereas mace comes from the red-colored covering layer, or aril, surrounding the nut. Nutmeg has long been used medicinally, in China to treat rheumatism and stomach pains, and in Southeast Asia for dysentery or colic. In Europe, as well as being considered an aphrodisiac and a soporific, nutmeg was worn in a small bag around the neck to protect against the Black Death, which swept Europe with regularity after its first recorded occurrence in 1347. While epidemics of other diseases (typhus, smallpox) periodically visited parts of Europe, the plague was the most feared. It occurred in three forms. The

bubonic

form manifested in painful buboes or swellings in the groin and armpits; internal hemorrhaging and neurological decay was fatal in 50 to 60 percent of cases. Less frequent but more virulent was the

pneumonic

form.

Septicemic

plague, where overwhelming amounts of bacilli invade the blood, was always fatal, often in less than a day.

bubonic

form manifested in painful buboes or swellings in the groin and armpits; internal hemorrhaging and neurological decay was fatal in 50 to 60 percent of cases. Less frequent but more virulent was the

pneumonic

form.

Septicemic

plague, where overwhelming amounts of bacilli invade the blood, was always fatal, often in less than a day.

It's entirely possible that the molecules of isoeugenol in fresh nutmeg did act as a deterrent to the fleas that carry bubonic plague bacteria. And other molecules in nutmeg may also have insecticidal properties. Quantities of two other fragrant molecules, myristicin and elemicin, occur in both nutmeg and mace. The structures of these two compounds are very similar to each other and to those molecules we have already seen in nutmeg, cloves, and peppers.

Besides being a talisman against the plague, nutmeg was considered to be the “spice of madness.” Its hallucinogenic propertiesâlikely from the molecules myristicin and elemicinâwere known for centuries. A 1576 report told of “a pregnant English lady, having eaten ten or twelve nutmegs, became deliriously inebriated.” The accuracy of this tale is doubtful, especially the number of nutmegs consumed, as present-day accounts of ingestion of only one nutmeg describe nausea, profuse sweating, heart palpitations, and vastly elevated blood pressure, along with

days

of hallucinations. This is somewhat more than a delirious inebriation; death has been attributed to consumption of far fewer than twelve nutmegs. Myristicin in large quantities can also cause liver damage.

days

of hallucinations. This is somewhat more than a delirious inebriation; death has been attributed to consumption of far fewer than twelve nutmegs. Myristicin in large quantities can also cause liver damage.

In addition to nutmeg and mace, carrots, celery, dill, parsley, and black pepper all contain trace amounts of myristicin and elemicin. We don't generally consume the huge quantities of these substances necessary for their psychedelic effects to be felt. And there is no evidence that myristicin and elemicin are psychoactive in themselves. It is possible that they are converted, by some as-yet-unknown metabolic pathway in our body, to traces of compounds that would be analogs of amphetamines.

The chemical rationale for this scenario depends on the fact that another molecule, safrole, with a structure that differs from myristicin only by a missing OCH

3

, is the starting material for the illicit manufacture of the compound with the full chemical name of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-METHYLAMPHETAMINE, abbreviated to MDMA and also called Ecstasy.

3

, is the starting material for the illicit manufacture of the compound with the full chemical name of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-METHYLAMPHETAMINE, abbreviated to MDMA and also called Ecstasy.

The transformation of safrole to Ecstasy can be shown as:

Safrole comes from the sassafras tree. Traces can also be found in cocoa, black pepper, mace, nutmeg, and wild ginger. Oil of sassafras, extracted from the root of the tree, is about 85 percent safrole and was once used as the main flavoring agent in root beer. Safrole is now deemed a carcinogen and, along with oil of sassafras, has been banned as a food additive.

NUTMEG AND NEW YORKThe clove trade was dominated by the Portuguese during most of the sixteenth century, but they never achieved a complete monopoly. They reached agreements on trading and building forts with the sultans of the islands of Ternate and Tidore, but these alliances proved temporary. The Moluccans continued to sell cloves to their traditional Javanese and Malayan trading partners.

In the next century the Dutch, who had more ships, more men, better guns, and a much harsher colonization policy, became masters of the spice trade, mainly through the auspices of the all-powerful Dutch East India Companyâthe Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOCâestablished in 1602. The monopoly was not easily accomplished or sustained. It took until 1667 for the VOC to obtain complete control over the Moluccas, evicting the Spanish and Portuguese from their few remaining outposts and ruthlessly crushing opposition from the local people.

To fully consolidate their position, the Dutch needed to dominate the nutmeg trade in the Banda Islands. A 1602 treaty was supposed to have given the VOC sole rights to purchase all the nutmeg produced on the islands, but though the treaty was signed by the village chiefs, the concept of exclusivity was either not accepted or (maybe) not understood by the Bandanese, who continued selling their nutmeg to other traders at the highest offered priceâa concept they did understand.

The response by the Dutch was ruthless. A fleet of ships, hundreds of men, and the first of a number of large forts appeared in the Bandas, all designed to control the trade in nutmeg. After a series of attacks, counterattacks, massacres, renewed contracts, and further broken treaties, the Dutch acted even more decisively. Groves of nutmeg trees were destroyed except around where the Dutch forts had been built. Bandanese villages were burned to the ground, the headmen were executed, and the remaining population was enslaved under Dutch settlers brought in to oversee nutmeg production.

The lone remaining threat to the VOC's complete monopoly was the continued presence of the English on Run, the most remote of the Banda Islands, where years before the headmen had signed a trade treaty with the English. This small atoll, where nutmeg trees were so numerous that they clung to the cliffs, became the scene of much bloody fighting. After a brutal siege, a Dutch invasion, and more destruction of nutmeg groves, with the 1667 Treaty of Breda the English surrendered all claims to the island of Run in exchange for a formal declaration renouncing Dutch rights to the island of Manhattan. New Amsterdam became New York, and the Dutch got nutmeg.

Other books

Exposed by Georgia Le Carre

Coach Amos by Gary Paulsen

Sharpe's Fortress by Bernard Cornwell

Mismatch by Tami Hoag

Her Best Worst Mistake by Sarah Mayberry

Second Time Around by Colette Caddle

Bound to the Wolf Prince by Marguerite Kaye

The Nightmarys by Dan Poblocki

Incarnations by Butler, Christine M.

Mary, Mary by James Patterson