Poison (14 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Uncle Iqbal got wind of the stories. He was furious, embarrassed. If he had known what Dhillon was up to, he reflected, he would have phoned the police. Yes, that’s what he would have done. He was not afraid of Jodha. He visited Surinder, who was the widow of Dhillon’s late brother, Darshan, and living at the family’s apartment in Ludhiana. “You knew this was happening,” he said to her. “Why didn’t you tell me about it?”

“Jodha threatened me,” she said. “He told me not to tell or he’d have me shot.”

Iqbal phoned Dhillon in Hamilton. “Why have you done all this to us?” he asked. “What do I tell Sarabjit and her family?”

“Tell them to do whatever they want,” Dhillon said. “Just tell them I ran away.”

On April 15, 1996, Dhillon filed papers to bring Sukhwinder Kaur to Canada.

Criminal poisoning is a rare offence. A behavioral profile of the poisoner looks something like this: one with a dreamy disposition who sees the world through a child-like prism, having an illusory sense of the world and their place in it; there is a strong desire to get their own way; they may have been spoiled as a child. Poisoners try to make the world obey their will by cheating it, at first in minor ways, taking what it refuses to deliver to them. Male poisoners may be vain, pretty boys, somewhat effeminate. They tend to be non-confrontational, having little in common with the killer who attacks in an alley with a baseball bat or gun. The poisoner depersonalizes victims, an extension of their failure to accept any moral basis for life in a world they see through their own cracked lens.That profile fit Sukhwinder Dhillon in the spring of 1996. But there was no criminal profile on him. No one in law enforcement was even looking for him.

Most killers murder in a paroxysm of disorienting hate, fear, rage, or dementia, when the brain’s circuits fatally cross in the blinding heat and confusion of the moment. The serial killer is different. He—and it is almost always a male—allows time to lapse between each victim in what homicide profilers call a cooling-off period. There is purpose and calculation, a rationality disturbing in its whispered suggestion that all humanity shares the capacity to kill, even if it is usually buried in a moral crevice that never sees light. The serial killer is, by definition, a successful killer. He is pushed on by his own sense of accomplishment, his ego fed but never satisfied by each murder he commits. He will not, cannot, be caught. And so he does not stop.

“Kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi

.” Now it was the next boy’s turn. In his pale blue uniform shirt and navy pants, little Ranjit Khela took a deep breath and ran across enemy lines on the playground, calling the word over and over again:

“Kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi.”

Ranjit touched a boy on the shoulder, sprinted to the next, just missed him, touched another, and another—“

Kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi!”

.” Now it was the next boy’s turn. In his pale blue uniform shirt and navy pants, little Ranjit Khela took a deep breath and ran across enemy lines on the playground, calling the word over and over again:

“Kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi.”

Ranjit touched a boy on the shoulder, sprinted to the next, just missed him, touched another, and another—“

Kabaddi-kabaddi-kabaddi!”

The boys played the game every day. Hold your breath, run across a line in the dirt to the other side, tag as many boys as possible before escaping back. Chanting the word repeatedly ensured you could not cheat by taking a breath. Ranjit ran faster now, his lungs screaming for air, heart pounding—“

Kabaddi-kabaddi!”

Could he touch one more, push it a little further, leave himself enough oxygen to make it back across the line? “

Kabaddi-kabaddi

”—Yes! Ranjit made it back. It was a game for healthy lungs.

Kabaddi-kabaddi!”

Could he touch one more, push it a little further, leave himself enough oxygen to make it back across the line? “

Kabaddi-kabaddi

”—Yes! Ranjit made it back. It was a game for healthy lungs.

Every day in the Punjabi village called Mau Sahib, he was up early helping on the family farm, harvesting wheat and rice, herding buffalo. As landowning

jats

(farmers), the Khelas were not poor. After morning chores, he walked 30 minutes to school from his family’s bungalow along a path made of dark brick, radiating heat, into the dusty village center where shops and produce stands lined the main dirt road. Every day, he passed the towering brick kiln and a stone-block funeral pyre. Right turn onto the main road, a canopy of banyan and eucalyptus trees, tall fields of sugar cane and rice tossing in the wind as though invisible children ran through them, and into the school courtyard. Games in the yard, then classes inside the plain gray concrete-walled rooms. It was a simple time. And the best chapter in Ranjit’s life.

jats

(farmers), the Khelas were not poor. After morning chores, he walked 30 minutes to school from his family’s bungalow along a path made of dark brick, radiating heat, into the dusty village center where shops and produce stands lined the main dirt road. Every day, he passed the towering brick kiln and a stone-block funeral pyre. Right turn onto the main road, a canopy of banyan and eucalyptus trees, tall fields of sugar cane and rice tossing in the wind as though invisible children ran through them, and into the school courtyard. Games in the yard, then classes inside the plain gray concrete-walled rooms. It was a simple time. And the best chapter in Ranjit’s life.

As a teenager he talked about the dream, making it overseas, finding his fortune. Ranjit was born on New Year’s Day, 1971, the first of four children. He grew up to be a tall, handsome man, the star of the family. He was a leader, he ran the farm. A life in Canada was inevitable. Davinder and Gurmail, Ranjit’s aunt and uncle, were the first to make it over, to Hamilton, Ontario. They sponsored his grandparents, Piara and Surjit, to follow. Ranjit stopped attending school after Grade 8 to work on the farm full time, drive the tractor, supervise workers the family hired for

harvest season. And, like some of his boyhood friends, he cut his hair for the first time, divorcing himself from orthodox Sikhism. After that he wore a turban only on formal occasions. In 1992, when Ranjit turned 21, the road to the new world opened for him when a woman named Lakhwinder visited him from Canada. Ranjit embraced the opportunity to join his relatives in Hamilton.

harvest season. And, like some of his boyhood friends, he cut his hair for the first time, divorcing himself from orthodox Sikhism. After that he wore a turban only on formal occasions. In 1992, when Ranjit turned 21, the road to the new world opened for him when a woman named Lakhwinder visited him from Canada. Ranjit embraced the opportunity to join his relatives in Hamilton.

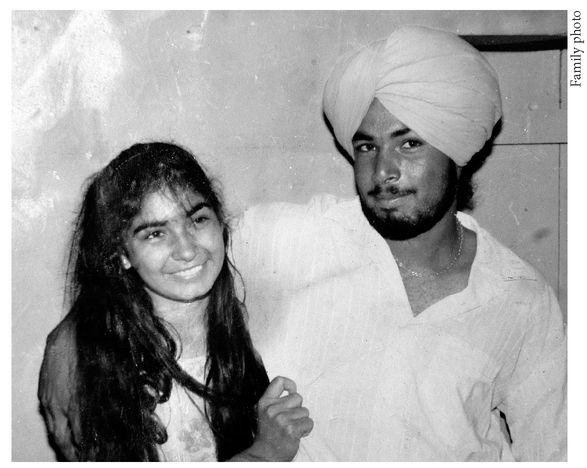

Ranjit Khela and his sister, Karmajit

Lakhwinder Kaur Sekhon had moved to Canada in 1987 and three years later signed on for an arranged marriage to an Indian man. Sixteen months later they divorced. Twenty-four months after that, she met Ranjit Khela. She had first seen him in a photo while visiting Ranjit’s relatives in Hamilton. If his family was willing to arrange a marriage, she was interested. The couple married in Punjab on December 13, 1992, in a village called Dakha. Ranjit’s 12-year-old sister, Karmajit, cried before her big brother left. She loved him so much, looked up to him. On October 23, 1993, Ranjit arrived in Canada.

He soon moved into an apartment in Hamilton’s east end and met Sukhwinder Dhillon. To Ranjit, Jodha seemed successful,

had his own house, a beautiful wife and two kids, sold used cars. Dhillon assumed the role of Ranjit’s mentor. He was 35, Ranjit—Ranna, they called him—was 23 years old. He knew little English. Dhillon spoke English, even if it was coarse. Dhillon was the wheeler-dealer, Ranjit his quiet understudy.

had his own house, a beautiful wife and two kids, sold used cars. Dhillon assumed the role of Ranjit’s mentor. He was 35, Ranjit—Ranna, they called him—was 23 years old. He knew little English. Dhillon spoke English, even if it was coarse. Dhillon was the wheeler-dealer, Ranjit his quiet understudy.

The two men talked about everything—cars, women, complained about their wives. Jodha’s wife always had headaches. Ranjit thought his wife was overweight and confided that he was having trouble getting an erection with her. The impotence frustrated him. He was too young to go through this. Repeated visits to two local doctors, three injections of testosterone. Nothing worked.

The friends became close enough that, when Dhillon traveled back to Punjab after the death of Parvesh, Ranjit looked after his house on Berkindale Drive. While in Punjab, Dhillon drove to Mau Sahib to deliver presents from Ranjit to his family. Ranjit had sent gifts to prove he was taking advantage of his new opportunity in Canada—shoes for his brothers, a gold Nike pendant for his cousin. Dhillon was met by Ranjit’s aunt. Accustomed to smaller Indian men, Dhillon appeared huge to her, like a giant. But she quickly moved from his physique to his eyes. What was it about them? What was going on in his mind? You look into a person’s eyes and sometimes you just know there is something wrong. That’s how it was. You could just tell. Dhillon was trouble.

In April 1996 Dhillon spoke with Ranjit about a property for sale on Barton Street East near Strathearne, a former gas station. This was where Dhillon wanted to realize his dream of building a used-car dealership. In April Dhillon signed an agreement to buy the land from Sunoco for $35,085. Now Aman Auto would have a real home. The deal was finalized on April 29. But Dhillon delayed closing the sale. May 30 was set as the new closing date. He needed more money. He delayed it again. And a third time. On May 1, Ranjit and Dhillon visited a small Allstate insurance outlet on Barton Street East. Dhillon did the talking, he knew more English, and it was his agent they met, a man named Stan

Ruhl. Dhillon said Ranjit was interested in buying car insurance. With Dhillon speaking in his rapid-fire English and Ranjit sitting quietly beside him, the talk turned to life insurance. Dhillon said they would like to name each other as beneficiary.

Ruhl. Dhillon said Ranjit was interested in buying car insurance. With Dhillon speaking in his rapid-fire English and Ranjit sitting quietly beside him, the talk turned to life insurance. Dhillon said they would like to name each other as beneficiary.

“What is your relationship to Ranjit?” Ruhl asked.

“I am Ranna’s uncle,” Dhillon lied. “He lives at my place. I take care of him. Taken care of him since he came to Canada.” He wrote down their information and the pair left the office. Ruhl was a tall, engaging, 54-year-old former steelworker who brushed his silver hair straight back. He found Dhillon a curiosity, the way he spoke so quickly, out of control, careening between broken English words and phrases, all of them running together—“

Heyhow’sgoingisthereanythingIcandoforyou

?”

Heyhow’sgoingisthereanythingIcandoforyou

?”

“Okay, okay, slow down,” Ruhl would say. “Okay? I can’t understand what you’re saying.” Ruhl’s horse sense said Dhillon was shady. Certain guys Ruhl considered to be in a gray area, character-wise. That was Dhillon. He once visited Ruhl’s office after one of his many trips to India, carrying a gift for the agent. Gold slippers.

“What is this for?” Ruhl said.

“Four hundred dollars, four hundred,” Dhillon said. “A gift for you.”

“Where the hell do you wear them? Down to the beach?”

“The gold is real, the gold in the slippers is real,” Dhillon said. “Worth a lot of money. All for you.”

Ruhl said no thanks. He didn’t take any gifts in his business, save for coffee and a doughnut at Tim Horton’s. On May 8, seven days after the first meeting, Ruhl, Dhillon, and Ranjit met again. Ranjit and Dhillon were clear to go ahead, uncle and nephew, a policy for each. The policies were issued for $100,000 with an additional $100,000 payable in the event of accidental death. Dhillon was the beneficiary if Ranjit died.

Dhillon phoned Sunoco. He was nearly ready to close the deal on the Barton Street property. Then, on June 16, he signed an agreement to delay the sale to July. He needed more time. Just a bit more.

Other books

The Lurking Man by Keith Rommel

The Big Sheep by Robert Kroese

Allegiant by Veronica Roth

Doorways to Infinity by Geof Johnson

Tropic of Creation by Kay Kenyon

Forbidden by Miles, Amy

The Anatomy of Violence by Charles Runyon

The Manual of Detection by Jedediah Berry

The Woman by David Bishop

The Darkfall Switch by David Lindsley