Poison (18 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

But court is one thing, a police investigation another. Homicide detectives seek the whole story, not one scrubbed of prejudicial notions. Sukhwinder Dhillon was a murder suspect. And you could add wife-beater to his resumé. Parvesh’s husband was a cruel man. A cowardly one. In time, after investigating, interviewing, researching, Warren Korol learned Parvesh’s story. It was not a pretty one.

As a little girl, Parvesh Kaur Grewal would walk from her house, past the large banyan tree in the street, up the dusty laneway, through the black gate to the public school. She loved school and her teachers. It would be wonderful if she could be a teacher herself. She lived in a crowded urban neighborhood in a village called Sahkewal, within Ludhiana’s city boundary. Her family owned a dairy and crop farm—larger than the Dhillons’—and their home adjoined several other bungalow-style units that over time they purchased. It was, for Ludhiana, a quiet residential area, none of the buzzing markets seen in other parts of the city. There were pockets of poverty, but also well-kept homes. Near the Grewal house, kids played in the narrow streets. At night it was quiet. The neighborhood contrasted with Birk Barsal, Dhillon’s neighborhood nearby, bursting with bustle and commerce.

Deep inside, beyond the expectations of her parents and culture, Parvesh had, like other educated Punjabi women, an inner sense of the possible, of other life destinations. But she kept those thoughts at bay. There was no other choice. The plan was laid out. As a young woman in a traditional Punjabi family, the paramount concern was ensuring you did not dishonor your parents in the eyes of the community. Her destiny changed forever in 1981, the year she was introduced and engaged by her parents to Sukhwinder Dhillon. When she arrived in Canada in 1983, Parvesh was 25, one year older than her husband.

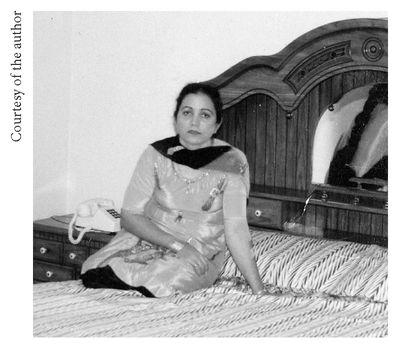

They were entirely different people. Sukhwinder had a thick, lumbering physique, dark skin. Parvesh was tall and slim, with uncommonly fair skin—almost like a white woman, Indians said. Fair skin on a female is revered in Indian society. Parvesh had teardrop-shaped green eyes, as though suggesting an unspoken inner pain that only she knew. Her husband’s eyes were like a slap in the face, with an intensity that seemed born of anger or wild-eyed confusion, as if he were trying desperately to absorb information about surroundings and people he did not understand. Parvesh was educated, he was not. She knew English and something of the world. He was a dreamer, brash and boastful. Parvesh lived to adulthood with both her mother and father alive; Dhillon’s father died when he was a boy, thrusting his mother into the center of his world. At their wedding, upon seeing the jewelry collected by Parvesh’s family for the dowry, Dhillon demanded more on the spot.

In Hamilton, while Dhillon avoided hard work, Parvesh labored at a mushroom farm. In the summer of 1984, each morning, she boarded a bus before dawn for the farm in Campbellville, north of Hamilton. She was a harvester, and harvest was every day. That meant slicing individual mushrooms from their trays, one by one, all day long. It was similar to working in a greenhouse, with one notable exception: no light. No light except for the one strapped to her head as if she were a miner, a tiny beacon guiding her way. “Women’s work” was how her husband described it, but he constantly pestered Parvesh to hand over her hard-earned money.

Parvesh Dhillon

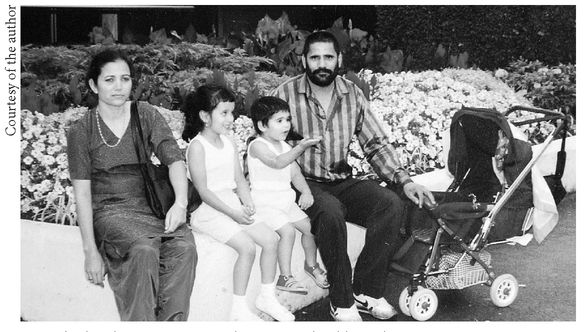

On July 26, 1985, she gave birth to their first child, Harpreet, by caesarean section. Six months later she returned to work, a new job at a textile factory. The following year, Parvesh miscarried her second pregnancy. Then she started work at a shoe factory. In 1988, the Dhillons’ second daughter, Aman, was born. Sukhwinder Dhillon was anxious to have a son. In May 1991, Parvesh was pregnant again. She traveled to India to have the fetus tested to determine its gender. She discovered it was a girl and had an abortion performed. Dhillon was so determined to have a son that he hired an immigration consultant to bring Parvesh’s eight-year-old nephew from India to live with them. His plan was to adopt the boy. He and Parvesh visited the consultant, a man named Parmagit Singh Mangat, in Etobicoke on September 18, 1992. Parvesh wore Western-style clothes, blue jeans. Mangat was struck by the contrast between the boorish Dhillon and Parvesh, who was gentle, sophisticated, beautiful. Nevertheless, her husband did most of the talking and made the decisions, even as they argued frequently.

Mangat did not know that Dhillon was out of work, on compensation. As the official sponsor for the boy, Dhillon signed a form claiming he worked at a place called Continental Auto Body in Hamilton and made $32,240 a year. Parvesh’s family in India fought Dhillon’s attempt at adoption. Parvesh and Sukhwinder returned to Mangat’s office a second time, and bickered even more. On the final visit, Dhillon came alone to see Mangat and cancelled the sponsorship attempt.

“We don’t want to do it any more,” Dhillon said. “I don’t want someone from my wife’s side of the family as a son anyway.”

Parvesh, daughters Harpreet and Aman, and Sukhwinder

Home movie: Aman’s birthday party. Harpreet is there, friends, in the basement of the house on Berkindale Drive. Children gather on the dark red carpet to watch the presents opened, excited young voices alternating between Punjabi and English. Parvesh, in a yellow dress, laughing with the girls, radiant smile, serving ice cream. The video camera is placed on a tripod. A man enters the frame. Her husband. Parvesh is on the couch and he sits beside her. Her smile vanishes, she glares at him. He playfully grabs at her dress, she swats his hand away. Parvesh rises from the couch, walks toward the camera, looks directly into the lens. A brief, silent stare, as though sending a message, no wink, no playful exasperation. For one moment the eyes are not aqua, they look black, as though offering an open window into her future with Sukhwinder Dhillon.

In August 1992, Parvesh worked at a factory on South Service Road called Narroflex, which made elasticized bands for clothing. It was the coolest, dampest, grayest summer anyone could remember in southern Ontario, oppressive in its bleakness. Her night shift over one day, Parvesh eased the car out of the parking lot, the factory noises still echoing in her head, another migraine beginning to build. She had worked at one of the machines for 12 hours straight. Great mounds of elastic cloth bands fed together

through her machine, then into smaller piles in boxes, appearing like mounds of snakes. She manned the machine—chick-chick-chick /whap-whap-whap/chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. Her job was making sure boxes were properly packed then taped shut and sent along a steel conveyor belt for delivery. 11:03 p.m. Chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap/chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. 11:05 p.m. Fifty-five minutes until her first hour finished, and the first $7.50 of the day. More bands, another box packed and taped and onto the belt. And on and on. The night grew old. Morning arrived. Chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap/ chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. Last box sealed. Parvesh was free to go home.

through her machine, then into smaller piles in boxes, appearing like mounds of snakes. She manned the machine—chick-chick-chick /whap-whap-whap/chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. Her job was making sure boxes were properly packed then taped shut and sent along a steel conveyor belt for delivery. 11:03 p.m. Chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap/chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. 11:05 p.m. Fifty-five minutes until her first hour finished, and the first $7.50 of the day. More bands, another box packed and taped and onto the belt. And on and on. The night grew old. Morning arrived. Chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap/ chick-chick-chick/whap-whap-whap. Last box sealed. Parvesh was free to go home.

She had just turned 34. She was weary, feeling what many Punjabi women experience after the initial excitement of Canada wears off. In Canada, everything is so busy, everyone works all the time. There is no escape from it. It was late morning. Parvesh drove along the quiet two-lane service road while, on the other side of the fence, beyond the road, cars on the QEW highway ripped by. Farther still, on the other side of the highway, was Van Wagner’s Beach. On a clear day, if she slowed her car, she could see Burlington across the water, and farther along the shore, like a miniature, the skyline of Toronto, the place she had landed nearly 10 years earlier. Her eyes heavy, Parvesh drove the 10 minutes to her house, excited at seeing her two daughters. Aman was four, Harpreet, seven. The girls were her life’s joy, they were all she talked about. Her husband wasn’t home. When was he going to return to work? How long had he been on compensation now? Parvesh had opened four bank accounts at three banks, trying to keep her money from his greedy hands.

Parvesh lay on her bed, closed her eyes. The headaches came so frequently, it seemed like every day. She saw a doctor regularly. Her overall health was fine, but the fist of pain in her back that spread to her head never stopped. She had a CT scan and an electroencephalogram. Both came up normal. The doctors described her pain as “ordinary muscle tension headaches.” Relax more, they told her. Remove the source of the stress. But she couldn’t

just remove her husband. The nights when Jodha had friends over were awful. Drinking downstairs, shot after shot of whisky, then the expectation, followed by the loud demand, that she make them all dinner. She would have to face the mess the next morning—leftover food, even on occasion vomit on the floor—and clean it up. This while she worked obsessively to keep a spotless house. But even the drinking parties weren’t as bad as the abuse, the moments when Jodha wrapped his thick hand around her slender neck and screamed threats in her ear, even that he would kill her.

just remove her husband. The nights when Jodha had friends over were awful. Drinking downstairs, shot after shot of whisky, then the expectation, followed by the loud demand, that she make them all dinner. She would have to face the mess the next morning—leftover food, even on occasion vomit on the floor—and clean it up. This while she worked obsessively to keep a spotless house. But even the drinking parties weren’t as bad as the abuse, the moments when Jodha wrapped his thick hand around her slender neck and screamed threats in her ear, even that he would kill her.

He once took Parvesh to one of the used-car auctions he attended as a dealer. He introduced her to the man who ran the place. The manager saw Parvesh, her head covered with a scarf, eyes glazed and distant. “So how d’ya put up with this guy?” he said, using a folksy expression. Dhillon smiled. Parvesh said nothing, her face frozen.

Her mother and father lived with them for stretches of time. Dhillon treated them with violent contempt. Friends heard that Dhillon swatted his in-laws with newspapers, hit them with kitchen utensils, used gutter language in their presence, or swore directly at them. The rumor was that Dhillon even stood naked in front of the parents, a sickening insult in the Punjabi culture. On Friday, August 14, Parvesh’s father, Hardev, was living there, working days on a chicken farm gathering eggs. At 6:30 a.m. the phone rang in the Dhillons’ home. The call was for Hardev. It woke Dhillon up. Six-thirty? The wife’s old man does nothing around here, and the phone rings for him at 6:30 in the morning? Parvesh, still asleep, felt a heavy hand grab her shoulder. She awoke to hear Jodha yelling at her, his voice stinging inside her head. She talked back. Parvesh was so much smarter. He never forgave her for that.

Other books

When Elephants Fight by Eric Walters

Poppin' Her Hood (Deflowering Virgin Erotica) by Kayla Calvert

The Silent Army by James Knapp

The Liverpool Rose by Katie Flynn

Elemental Desire by Denise Tompkins

Play Me, I'm Yours [Library Edition] by Madison Parker

I Have Iraq in My Shoe by Gretchen Berg

When Things Get Back to Normal by M.T. Dohaney

The No Where Apocalypse (Book 1): Stranded No Where by Lake, E.A.

La hija del Adelantado by José Milla y Vidaurre