Poison (12 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

CHAPTER 6

BURNING CORPSE

Panj Grain, India

December 1995

December 1995

Sarabjit waited for the moment, her slim young figure transformed by the offspring of Sukhwinder Dhillon growing inside her. The birth would come any day now. She had checked into Kumar Hospital, a 15-minute drive from Panj Grain. In a marriage that had been long distance at best, and nightmarish when she was with her husband, the anticipation of being a mother excited her. And Jodha, her husband? Dhillon sounded surprised when she first told him that she was expecting. But why should he be? Had they not had sex nearly every day they spent together? She wondered how he would react when he saw the baby for the first time. When she spoke to him on the phone, he told her he was due to arrive in India any day now, would likely meet her at the hospital.

In fact, Dhillon was already in Ludhiana. He had flown out of Toronto along with his mother, brother, and his daughters on Friday, December 8, arriving in New Delhi on Monday, December 11, well aware that Sarabjit would soon deliver. But he avoided her. He had other business.

On Tuesday, he arrived at his home in Ludhiana. Rai Singh Toor showed up at the door. Rai Singh was the father of Dhillon’s third wife, Kushpreet. Good news, Rai said. He had medical papers for Dhillon to sign to help speed Kushpreet’s entry to Canada. Dhillon had married her in April, but still had not had sex with her. Rai Singh had made it clear that would not happen until her immigration papers were finalized. The next day, Wednesday, December 13, Dhillon drove two hours to Kushpreet’s village, Tibba. He arrived, exchanged pleasantries with Rai Singh, enjoyed a cold drink, and handed over the papers. Would he stay for the evening? No, he should really get home. He and Kushpreet had things to do, and he had other business to take care of.

Dhillon drove Kushpreet back to his house in Ludhiana to consummate their marriage. Rai Singh phoned the next day,

determined to see the Canadian immigration expedited. Kushpreet needed to have a physical as part of the immigration process. When did Dhillon want to take her for it? Tomorrow, tomorrow, said Dhillon, stalling. The next day was Friday, December 15. At six-thirty in the morning, Sarabjit lay in her hospital bed, exhausted, a newborn baby in each arm. She had gone into labor just after six the evening before, gave birth 12 hours later. Sukhwinder Dhillon finally had a son—two sons, in fact. Twins. Sarabjit proudly told the nurses the names she picked for the twin boys: Gurmeet and Gurwinder. She just liked the sound of them. The nurses liked the names, too. The boys entered the world eight months and 10 days after Sarabjit’s wedding to Dhillon.

determined to see the Canadian immigration expedited. Kushpreet needed to have a physical as part of the immigration process. When did Dhillon want to take her for it? Tomorrow, tomorrow, said Dhillon, stalling. The next day was Friday, December 15. At six-thirty in the morning, Sarabjit lay in her hospital bed, exhausted, a newborn baby in each arm. She had gone into labor just after six the evening before, gave birth 12 hours later. Sukhwinder Dhillon finally had a son—two sons, in fact. Twins. Sarabjit proudly told the nurses the names she picked for the twin boys: Gurmeet and Gurwinder. She just liked the sound of them. The nurses liked the names, too. The boys entered the world eight months and 10 days after Sarabjit’s wedding to Dhillon.

A day after the births, Dhillon left Kushpreet long enough to phone Sarabjit in the hospital. He was in India now, finally, he told Sarabjit. She thought he sounded happy when she told him he had two sons. Or maybe just surprised. Who cared how he felt, really. Except, in Sarabjit’s current state, weary from childbirth, ecstatic at the twin wonders, she let herself think that maybe Jodha would be excited. He had never had a son, and now she had given him two. It had been seven months since she last saw him. Perhaps things had changed, perhaps things would improve when they were together in Canada.

“I’ll come as soon as possible,” Dhillon told her. “I have some business, but will be right there.”

Dhillon then phoned Sarabjit’s father in Panj Grain, a man named Gurjant. Dhillon had a message for him to pass on to Sarabjit. Later, Gurjant walked into his daughter’s hospital room. They chatted briefly, then he got to the point. Dhillon had called, he said.

“Why? Why did he call you?” she said.

“He has asked that you keep the babies unnamed,” Gurjant said.

“What?”

“That’s what he said.”

Sarabjit’s father didn’t quite understand Dhillon’s reasoning, but he also didn’t want to upset him. Dhillon was his ticket to Canada, too.

“I have already named them,” Sarabjit said. “Gurmeet and Gurwinder. That’s it.”

They argued briefly. Gurjant had never seen this side of his daughter before. Sarabjit’s voice grew angry. “You married me to him, and now I have my own life. The naming will be done—it is done. I’m making my own decisions.”

Gurjant left the room and Sarabjit realized she was short of breath. This was an outrage. How could Dhillon demand such a thing, and use her father as the messenger, no less? A nurse entered the room. Was she all right? “Oh yes,” Sarabjit said. “When can I sign the forms registering the babies’ names? I want to sign them. The names are picked.”

On Wednesday, December 20, Dhillon told Kushpreet he had business in Chandigarh. He was a busy man. She should stay put. Dhillon left, bought some candy for Sarabjit, and drove two hours to the hospital. A nurse congratulated him on the news. He sat on the bed beside Sarabjit and handed her a bottle of tonic. Rub it over the babies, he said, it will make them strong. Then he held his sons. He turned to Sarabjit. Don’t tell anyone about the babies, he said, don’t make a big fuss over it. And do not yet name them.

“What?” she said.

“A wise man told me. The stars are not right. It will be bad luck. And another thing, do not hang the

sehara

at home.” A

sehara

is a wall-hanging of flowers, often hung on a gate of a house to celebrate the birth of a son. Sarabjit was outraged. Who was this man? How could he say such things?

sehara

at home.” A

sehara

is a wall-hanging of flowers, often hung on a gate of a house to celebrate the birth of a son. Sarabjit was outraged. Who was this man? How could he say such things?

“It’s too late,” she said, defiance swelling inside her. “I’ve named them already.”

Dhillon became angry. “How could you when I asked you not to?”

“They need names,” she said. “And so I have named them.”

Sarabjit was due to leave the hospital the next day, but Dhillon told her she could not yet join him in Ludhiana. He had business to tend to, and immigration matters to expedite. He told her to stay at her parents’ Panj Grain home with the newborns. Dhillon left the hospital and drove back to Ludhiana to be with Kushpreet. He had something for her, something he had brought

from Canada. It would help her qualify for immigration. It was a single medicine capsule.

from Canada. It would help her qualify for immigration. It was a single medicine capsule.

“If you are pregnant, they won’t let you come to Canada,” he explained. “This pill, I brought it from Canada, it’s medicine that will help. We’ve been having sex, this will keep you from getting pregnant.”

“Yes, but not yet,” she said. “I need to speak with my mother first.”

Two weeks later, on December 27, Dhillon brought Kushpreet back to her home in Tibba. Dhillon saw Sukie, his wife’s younger sister. “You know, we should get married, don’t you think?” he said. Jodha. Always joking like that.

Dhillon left alone. He had somewhere to go, business in New Delhi, he said. He got back in his car and drove the two-hour trip (all trips on India’s congested roads seemed to take at least two hours) to Panj Grain to visit Sarabjit and the twins. After Dhillon left, Kushpreet spoke to her mother, Daljit. Kushpreet was embarrassed about her relationship with Dhillon. She told her mother about the pill and what Dhillon wanted her to do.

“That’s ridiculous,” Daljit said. “Don’t take it. You’re married, after all. If you are pregnant, so be it. And I’ve never heard of one pill that would do that.”

Later that day, Dhillon arrived in Panj Grain, driving past the village fields and the brick-walled, rectangular cemetery. Cemeteries are not common sights in Punjab. Sikhs cremate their dead, sprinkle the ashes in the river. The few cemeteries that exist are mainly for infants. Babies that die are not cremated. An infant is believed to have not yet developed a soul, and so has no relationship with God to pursue once the body is burned.

At Sarabjit’s family home, Dhillon sat alone with the babies while his wife joined her mother in the kitchen to make tea. What was it that angered him so much about naming the babies? Was it that naming the kids would identify him to everyone as her husband, something he could not allow? Sarabjit and her mother came back in the room, and Dhillon said he could not stay for dinner, which is an insult in Punjabi culture. He was sorry, but he had to go, right now. He left at 8 p.m. It occurred to Sarabjit that this was

the first visit since her arranged marriage with Dhillon that he had not insisted on sex. And now was he leaving, after just four hours with his new sons. Why had he even come? she wondered.

the first visit since her arranged marriage with Dhillon that he had not insisted on sex. And now was he leaving, after just four hours with his new sons. Why had he even come? she wondered.

Dhillon vanished into the blackness of the country night. He drove to Tibba, picked up Kushpreet, and headed toward Ludhiana.

Sarabjit watched her babies die in agony.

Meanwhile, at 10 o’clock, back in Panj Grain, Sarabjit heard one of the babies crying. It sounded more intense than usual. As Gurmeet slept, Sarabjit picked up Gurwinder from his crib. She was frightened. She had fed him nothing but goat’s milk before bed, as usual. She rocked him, tried to hum a song. She could feel his tiny body shaking. In the dim light she could see that his hands and feet had a blue tone to them. Terrified now, she felt the little body convulse, his neck, arms, and legs stiffen. He vomited a dark green fluid. Sarabjit’s father took Gurwinder from her arms and rushed him to the local temple to see the priest. It was a Sikh tradition to take a sick baby to a priest for prayers. Sarabjit wanted to go, but was told to stay put. Women were told to stay indoors at night. It was cool outside, so he wrapped the baby in blankets.

At the temple the priest held the boy, blessed him, spoke soothingly. But it was no use. The baby boy died. The male members of Sarabjit’s family—for tradition dictates that only males can

undertake such a ritual—buried him in the cemetery. Sarabjit wanted to go to the funeral. The men told her she could not.

undertake such a ritual—buried him in the cemetery. Sarabjit wanted to go to the funeral. The men told her she could not.

Her uncle Iqbal, who had first set Dhillon up with Sarabjit, phoned Dhillon to tell him the terrible news and inform him about the funeral. At the apartment in Ludhiana, Dhillon’s sister-in-law answered. Dhillon told her to say he wasn’t home. He did not attend the burial of his son. Later that same day, baby Gurmeet also became ill. This time the family phoned a local doctor’s apprentice. He didn’t know what to make of it. Take the baby to a hospital, a specialist, he said. Gurmeet’s death mirrored his brother’s: the convulsions, bloated stomach, blueish skin, green vomit. He died at 3:30 a.m. the next day. He was buried next to his brother. Both babies were laid to rest wearing their matching blue nylon pajamas.

Sarabjit, crushed, could only watch outside through the green steel gate guarding the pathway to the walled cemetery, tears pouring down her cheeks. Once again, her uncle Iqbal had called Dhillon’s home. Again, the father of the babies did not appear to be around. He missed the second funeral as well. Later that day, Dhillon finally made the drive to Panj Grain to see his grieving wife. His face showed no emotion. He put his arm around Sarabjit. “

Udaas na ho, bachey saadey hey hee nahee see

,” Dhillon said. “It’s okay, don’t cry. The twins never belonged to us.”

Udaas na ho, bachey saadey hey hee nahee see

,” Dhillon said. “It’s okay, don’t cry. The twins never belonged to us.”

Sarabjit knew, or thought she knew, what he was trying to say, clumsily as usual—that the boys belonged to God. But after his insistence that she tell no one about their newborns, and not register their names, his words carried an ominous ring to them.

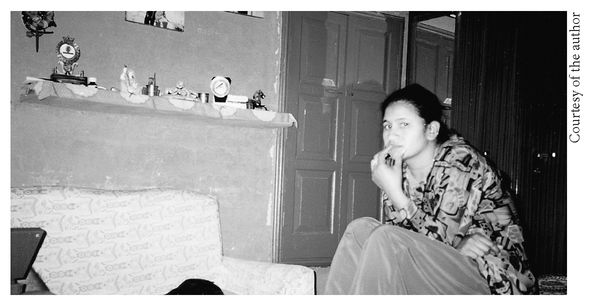

Dhillon left and returned to Ludhiana. The next morning, Sunday, December 31, Dhillon was on the road again, alone. This time he headed to a village called Dhandra. He showed up at the house of a man named Narangh Singh Grewal. Dhillon walked down a dark hallway, then into a main bedroom and living area, light shining through an ornately shaped window, pistachio green walls inside, lined with prints of Sikh gurus. He was interested in marrying Narangh Singh’s daughter. Dhillon had earlier directed his sister-in-law to ask around to see if there was any girl in the village who wanted to marry a Canadian man.

The young woman lined up for him was 27-year-old Sukhwinder Kaur Grewal.

The young woman lined up for him was 27-year-old Sukhwinder Kaur Grewal.

Sukhwinder Kaur did not find Dhillon appealing. He had an odd aura about him. She instantly disliked him. Dhillon spoke with her briefly and mentioned his first wife, Parvesh. A sad story, yes. He had taken her to Canada. She had been fasting, was quite weak, and slipped going down the stairs of their home in Hamilton. She died from the fall. Sukhwinder Kaur was older than Sarabjit or Kushpreet. She had a feisty spirit and knew the rules. Her parents struck a deal with Dhillon that day, and she was instantly engaged. They should be married in Canada, all agreed. Dhillon vowed to return to see the family on January 12.

Sukhwinder Kaur, Dhillon’s fourth wife

Other books

Sovereign of Stars by L. M. Ironside

Run: An Emma Caldridge Novella: The Final Episode by Jamie Freveletti

Meg's Best Man: A Montana Weekend Novella by Bruner, Cynthia

Slow Dancing on Price's Pier by Lisa Dale

Vanish by Tom Pawlik

Love Songs by MG Braden

Jake's Biggest Risk (Those Hollister Boys) by Julianna Morris

Tener y no tener by Ernest Hemingway

Goddess of Death by Roy Lewis

Lachlei by M. H. Bonham