Poison (9 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Somehow it works, this free flow where the fast and the large get priority and no one takes umbrage at this fact of life. Indian traffic is a communal, cooperative activity. Yet it balances on the head of a pin, for if just one person disregards a horn or fails to use their own or loses trust in another driver, it can mean death.

Now, leaving Toronto for Hamilton, Sukhwinder and his mother were on this superhighway, and it was staggering. The surface was like driving on marble, the car glided along as though on air, silently, no car horns; the road was black and clean, white lines shining in the dark as though lit by electricity, magically keeping traffic in different lanes, a spartan orderly progression. And there was no traffic coming at you the other way. You drove in one of your four or five lanes, and were separated from the oncoming traffic by a wall. There were no villages to wind through, no railway crossings where a corrupt official lowered the wooden arm, blocking everybody for an hour in order to accommodate the roadside merchants who paid him off. In the moonlight and the fluorescence of the street lamps, the cars looked so new, clean:

deep blues and greens, red, black, yellow, even, all of them reflecting light like diamonds. It was not just a few fancy cars like the ones that carried local political figures in Punjab, with their cherry-top sirens announcing a representative’s journey through town. No, in Canada, they were all fancy. So much money. Back in Ludhiana, the Dhillon family was relatively wealthy. Canada, for Sukhwinder and his mother, offered not economic survival, but gold at the end of the rainbow, a promised land of riches.

deep blues and greens, red, black, yellow, even, all of them reflecting light like diamonds. It was not just a few fancy cars like the ones that carried local political figures in Punjab, with their cherry-top sirens announcing a representative’s journey through town. No, in Canada, they were all fancy. So much money. Back in Ludhiana, the Dhillon family was relatively wealthy. Canada, for Sukhwinder and his mother, offered not economic survival, but gold at the end of the rainbow, a promised land of riches.

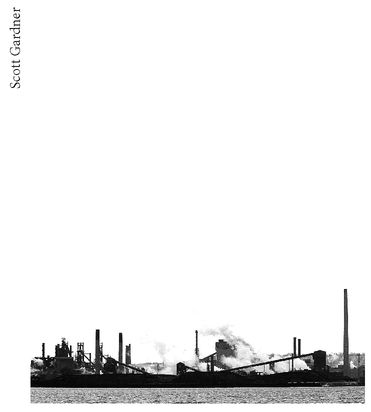

At Hamilton they crossed the Skyway bridge, swells on the lake turned silver by moonlight. They saw Canada’s Big Steel, smoke-stacks billowing, flames grasping at the blackness. The Dhillons—Sukhwinder, Gobind, brother Sukhbir, and his wife, Ravinder—all lived in a narrow two-storey brick house on Rosslyn Avenue North, in an earnest, working-class neighborhood not far from Gage Park. The Canadian dream was here, but in 1981 the path for Indians—“East Indians” they were called by Canadians—was not a glamorous one. Dhillon saw his older brother go to work every day as a chipper at Brown Boggs Foundry. It wasn’t far from the house where they all lived, in the shadow of Hamilton’s industrial heart. To Indians accustomed to Ludhiana’s gritty pollution and chaos, Hamilton was quiet and clean. Sukhbir eventually left the foundry, became a bus driver. What would young Sukhwinder do?

Industrial skyline of Hamilton, Ontario

In 1983 Dhillon returned to Ludhiana to wed Parvesh Grewal, the young woman his parents had arranged for him to marry. Dhillon and Parvesh lived in the house on Rosslyn Avenue North with Sukhbir and his wife, Ravinder. He worked briefly at a mushroom farm, earning

$4 an hour, then later got a job in a cheese factory. Then, like Sukhbir, he landed at the Brown Boggs Foundry. He was now making $14 an hour. His resumé was an earnest one, on paper. Reality was something else. He often didn’t show up for work at Boggs but had a co-worker punch his time card. For a short time Dhillon drove a cab, but his scatter-brained nature didn’t serve him well trying to navigate the city. He and Parvesh briefly moved to an apartment of their own on Queen Street North, then into a two-storey brown brick house on Rosslyn, a little north of where Sukhbir lived.

$4 an hour, then later got a job in a cheese factory. Then, like Sukhbir, he landed at the Brown Boggs Foundry. He was now making $14 an hour. His resumé was an earnest one, on paper. Reality was something else. He often didn’t show up for work at Boggs but had a co-worker punch his time card. For a short time Dhillon drove a cab, but his scatter-brained nature didn’t serve him well trying to navigate the city. He and Parvesh briefly moved to an apartment of their own on Queen Street North, then into a two-storey brown brick house on Rosslyn, a little north of where Sukhbir lived.

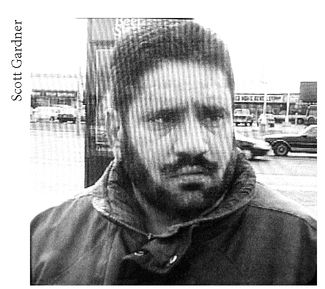

Dhillon at a used car sales lot in Hamilton

Dhillon—

Jodha

—earned a clownish reputation in the local Indian community. He spoke Punjabi in broken sentences, quickly, peppered with vulgarity, talked nonsense in a nasal tone. The tell-tale sign of his poor education, everyone knew, was his English. All educated Sikhs new to the city spoke decent English. That included Parvesh. But Dhillon spoke no English, at first. He picked it up later, not from the classroom like the others, but from the street, friends, television. When he spoke English it was often gibberish, the words strung together incorrectly, quickly repeated over and over. His behavior made him an easy target. Dhillon was always anxious to please, was easily swayed by any suggestion, and was comically boastful, with an instinct for lying, and lying big. He would meet someone for the first time and brag that he was a champion wrestler back in Ludhiana. In truth his wrestling had never extended beyond horseplay with other kids. He portrayed his life in India as a tableau of sensational adventures and feats of strength. Listeners couldn’t tell if Dhillon was joking or delusional, or if he was really the tough guy he described. His friends learned to tune him out.

Jodha

—earned a clownish reputation in the local Indian community. He spoke Punjabi in broken sentences, quickly, peppered with vulgarity, talked nonsense in a nasal tone. The tell-tale sign of his poor education, everyone knew, was his English. All educated Sikhs new to the city spoke decent English. That included Parvesh. But Dhillon spoke no English, at first. He picked it up later, not from the classroom like the others, but from the street, friends, television. When he spoke English it was often gibberish, the words strung together incorrectly, quickly repeated over and over. His behavior made him an easy target. Dhillon was always anxious to please, was easily swayed by any suggestion, and was comically boastful, with an instinct for lying, and lying big. He would meet someone for the first time and brag that he was a champion wrestler back in Ludhiana. In truth his wrestling had never extended beyond horseplay with other kids. He portrayed his life in India as a tableau of sensational adventures and feats of strength. Listeners couldn’t tell if Dhillon was joking or delusional, or if he was really the tough guy he described. His friends learned to tune him out.

Dhillon said people feared him back home, and even claimed to possess, literally, a black tongue—the

Kallijeeb

that Indian lore

said was the sign of an evil man. (One friend swore that Dhillon’s tongue was, in fact, black. Saw it with his own eyes.) Dhillon had a bearish physique, with round, thick shoulders. His protruding belly, however, betrayed softness below the surface. Still, he delighted in boasting of his strength, the weight he could lift. He told the stories and others listened in amazement. Was he for real?

Kallijeeb

that Indian lore

said was the sign of an evil man. (One friend swore that Dhillon’s tongue was, in fact, black. Saw it with his own eyes.) Dhillon had a bearish physique, with round, thick shoulders. His protruding belly, however, betrayed softness below the surface. Still, he delighted in boasting of his strength, the weight he could lift. He told the stories and others listened in amazement. Was he for real?

In September 1986, Dhillon started a job at J.I. Case, a sprawling factory on Sherman Avenue North that manufactured farm machinery. The steady pay, along with Parvesh’s earnings, ultimately allowed them to move to a house in Stoney Creek, a suburb east of Hamilton, on Berkindale Drive. It was near the Riverdale neighborhood, a place where Indians new to Hamilton had congregated since the late 1970s. Eventually the community grew enough to require a temple; the new

gurdwara

was a nice enough building, red brick with domed shapes etched into the walls. It sat like a lone healthy tooth on Covington Street, a dusty gray stretch of industrial road wedged between Barton Street and the QEW highway.

gurdwara

was a nice enough building, red brick with domed shapes etched into the walls. It sat like a lone healthy tooth on Covington Street, a dusty gray stretch of industrial road wedged between Barton Street and the QEW highway.

Dhillon worked at several stations at the plant, on the assembly line hanging small pieces on a line for painting, then removing them afterwards. The work was not heavy labor, but it was boringly repetitive. He also did what the guys called “bull work” in the heat of the forger, loading steel into a furnace, picking up the glowing red piece with tongs and holding it for a hammer man to crush. It was hot, heavy, dangerous work. Dhillon hated bull work because it required effort, but it did allow him to indulge in his fantasy of being the strong man. A man named Cliff Hewer supervised him. Dhillon seemed to be off work quite a bit. On occasion, Hewer phoned his house to check on him. Invariably, he would speak to Harpreet, Dhillon’s five-year-old daughter. Her dad was not there, she would say.

Hewer had some excellent workers of Indian origin. One of them was a man named Gurmej Khattra. Gurmej grew up on a prosperous farm in a village called Chahalkalan, in the Ludhiana area. He had always worked hard. When he turned five he helped his father in the fields in the morning, attended school during the day, then worked on the farm at night. A tall man with thick hands and broad smile, Gurmej possessed an independent, adventurous spirit. He worked

for a time on a Greek cargo ship and sailed for three years on routes between England, the Great Lakes, and Africa. One day, the ship docked at Hamilton Harbor and he deboarded for the last time. He was alone, starting from scratch. He eventually married a Canadian girl from Sudbury, had two children, was hired at J.I. Case as a punch press operator the same year as Sukhwinder Dhillon.

for a time on a Greek cargo ship and sailed for three years on routes between England, the Great Lakes, and Africa. One day, the ship docked at Hamilton Harbor and he deboarded for the last time. He was alone, starting from scratch. He eventually married a Canadian girl from Sudbury, had two children, was hired at J.I. Case as a punch press operator the same year as Sukhwinder Dhillon.

One day in the fall of 1986, Dhillon was sitting in his usual spot in the huge Case lunchroom. There was a table of about a dozen Indian men among the 80 or so in the entire room. Dhillon, the new guy, took center stage. I’m strong, stronger than all of you, he boasted. Back home, I was the strongest in the village. The other men egged him on. “Oh, Dhillon,” one of his Indian co-workers said with a grin. “You are a big man. No question about it, you are the biggest man.” Sarcasm didn’t appear to register in Dhillon’s mind. Maybe he understood it completely, but reveled in his role as the clown, the only role he felt he could play. Suddenly, Dhillon was on the lunchroom floor, the others looking on with broad grins. One. Two. Three. Pushups—he was doing pushups for them, weighed down in his workpants and boots.

“That’s pretty impressive. But what about situps?”

Dhillon moved outside now, through an adjacent door into a courtyard. One. Two. Three. He curled his body for the situps, folding his belly over and over. The others laughed. Dhillon, they thought, the guy’s nuts, brain-dead. Dhillon’s performance complete, he stood, walked back inside, forehead flecked with sweat.

At a table sat Gurmej Khattra. He was one of Dhillon’s first friends in Hamilton, but the pair hadn’t spent much time together in recent months. A couple of the other guys saw a new opportunity to push Dhillon’s buttons. They knew Gurmej was married to a white Canadian woman. “Hey, Dhillon—what do you think of Canadian women?” Dhillon took the performance up a notch.

“White women,” Dhillon said, looking at Gurmej, “are sluts.” Gurmej knew Dhillon talked nonsense. But he was still taken aback. He sat stone-faced. Dhillon, pleased by the reaction of the others, bore on. “Yeah, sluts,” he repeated. “Whores. All of them. Right, Gurmej?” Gurmej Khattra let it go. Dhillon was crazy. And Gurmej wasn’t going to do anything that would lose him his job.

Dhillon’s bluster around friends reflected his yearning for respect, his hunger for approval and his inability to sense how he was actually perceived. Dhillon lacked strength or guile. But he wielded his audacity like a weapon. And he lied, often. Others noticed something in Dhillon’s eyes when he lied. Or rather, they saw the absence of something—the wavering light of conscience. But he picked his spots for boasting and buffoonery. At work, managers thought Dhillon was a quiet man—he blended in, he was unremarkable. But among the guys from India, it was different. He invited them to his home, had Parvesh cook big meals, pass around his whisky for the boys. The binges got so out of control there were times they urinated and vomited on the carpet. Whenever Dhillon was challenged to drink, he would take them up on it.

“Dhillon—think you can drink a 40-ouncer?” The story went that Dhillon did it, downing an entire bottle over one evening on a bet, then throwing up repeatedly on the floor. At J.I. Case, meanwhile, for no reason Gurmej Khattra could figure out, Dhillon became increasingly aggressive toward him, the insults turning violent. Several days after the lunchroom incident, Dhillon strapped a sharp piece of pressed metal from the factory floor, slightly longer than a knife, under his pant leg, right in front of a co-worker.

“Dhillon, what the hell are you doing?” He grinned. It was for Gurmej. After work, Dhillon followed Gurmej to the gate. He pulled out the weapon. “

Teri ma noo

!” he shouted in Punjabi, using the worst slur in the language. (“Come on, motherf—! Come here, I’ll kill you!”) A co-worker stepped between the two, told them to stop it, they would get fired. Gurmej got in his car.

Teri ma noo

!” he shouted in Punjabi, using the worst slur in the language. (“Come on, motherf—! Come here, I’ll kill you!”) A co-worker stepped between the two, told them to stop it, they would get fired. Gurmej got in his car.

“I don’t want to fight,” he said out the window. “I don’t want trouble. I’m not union here, I’m not going to get fired.” Dhillon marched to the car and Gurmej rolled up the window.

“I’ll wait for you at your apartment!” Dhillon shouted. “I’m going to kill you.

Teri ma noo.

” Dhillon knew where Gurmej lived. How far would he take the act? Gurmej went home, but Dhillon never showed. A few days later, on a Saturday, Gurmej, his wife Cathy, and their little daughter Angel, got out of their car in the parking lot of a supermarket at Centre Mall on Barton Street.

Teri ma noo.

” Dhillon knew where Gurmej lived. How far would he take the act? Gurmej went home, but Dhillon never showed. A few days later, on a Saturday, Gurmej, his wife Cathy, and their little daughter Angel, got out of their car in the parking lot of a supermarket at Centre Mall on Barton Street.

Other books

What He Desires by Violet Haze

Runes #03 - Grimnirs by Ednah Walters

Tessa in Love by Kate Le Vann

A Girl's Best Friend by Jordan, Crystal

Cool Down by Steve Prentice

No New Land by M.G. Vassanji

For Love of the Duke (The Heart of a Duke Book 2) by Christi Caldwell

Jamestown (The Keepers of the Ring) by Hunt, Angela, Hunt, Angela Elwell

101 Slow-Cooker Recipes by Gooseberry Patch