Poison (8 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Dhillon had some other deals in mind, too. He planned a return trip to India. Perhaps he should find another wife. Was there any reason not to? In the spring of 1995, Dhillon was invincible. His dreams were coming true. And it was just the beginning.

CHAPTER 4

A PATHOLOGICAL GREED

New Delhi, India

1981

1981

Gobind Kaur Dhillon and the youngest of her three sons, Sukhwinder, boarded a flight at Indira Gandhi Airport in New Delhi for the trip to Canada. It was 1981 and Sukhwinder was 22 years old.

Punjab is India’s wealthiest state; many who live there see themselves as separate from the rest of the country. Relative to Indians in the south living in dire poverty, Punjabis have wealth, entertain the possibility of increasing that wealth, and Canada has long been the place to do it. For years there has been a sea of colorful turbans outside the Canadian High Commission in New Delhi, more than 100 of them at any time, seeking visas. Helping Punjabis get to Canada is big business. The posters are everywhere in the state—“World’s Largest Canadian Immigration Service”—on poles in the cities or painted in Maple Leaf red and white on pump houses amid the cane fields in the countryside: “Your passport to Canada!” The easiest way to accomplish it is family reunification.

A billboard in Ludhiana advertises immigration consultants

In 1981, the parents of a pretty young woman named Parvesh Kaur Grewal shared that yearning for Canada. There was a man her age named Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon who was moving to Canada with his mother. An arranged marriage with him was the ticket for their family to also make

it. Dhillon was engaged to Parvesh before he left with Gobind for Canada. The plan was that after planting roots overseas, he would return to marry Parvesh and bring her back. The jet took off from New Delhi, a stop in London, then the parabolic flight over Greenland, the descent over northern Quebec, the St. Lawrence River snaking through green hinterland below. Neither mother nor son had ever been outside India before.

it. Dhillon was engaged to Parvesh before he left with Gobind for Canada. The plan was that after planting roots overseas, he would return to marry Parvesh and bring her back. The jet took off from New Delhi, a stop in London, then the parabolic flight over Greenland, the descent over northern Quebec, the St. Lawrence River snaking through green hinterland below. Neither mother nor son had ever been outside India before.

Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon was the third and last son of Fagun and Gobind Dhillon. He was born May 9, 1959. His arrival in the world surely came as a surprise, for his mother had last given birth to her son Sukhbir 11 years earlier. Their eldest son was Darshan. Rambunctious Sukhwinder rolled around the living room of their walk-up apartment, a ball of mischief even before he could walk. His father, tongue in cheek, tagged the infant Jodha —brave warrior—and Dhillon proudly carried the name with him into his adult life.

His father owned a farm, wealth his three sons would one day inherit. Fagun Singh Dhillon had started with a handful of buffalo on his dairy farm, a few calves. Later the herd expanded to 40 head with four servants to care for the livestock. How Fagun came into his wealth was not entirely clear. He had been a career police officer for years but, not long after Sukhwinder was born, he abruptly left the police force. Why? The explanation became murky in family accounts. Gobind said it was because corruption on the force turned Fagun’s stomach, so he got out despite pleas to stay from the chief. Others in the family had a different interpretation than Gobind’s. Corruption has long been endemic in Indian law enforcement—beatings, forced confessions, bribery, confiscated property. Modern reforms reflect the ugly past. For example, any witness statements taken by police are inadmissible in court. Fagun was in fact quite a player himself. He didn’t leave the force—he was fired.

It may have been the defining moment in Sukhwinder Dhillon’s life. One day in 1964, when he was just five, he heard the news

that his father had died suddenly, and young. Practically speaking, it meant Sukhwinder, little Jodha, already spoiled as the baby and center of attention in a family with means, had no father to discipline him and inject reality into his fantasy world. He was young enough to feel little pain at Fagun’s death, having been told that there was no need to grieve. Fagun had led a successful life. And death is God’s will. Do not grieve. You needn’t feel—anything. More ominously, something peculiar may have taken root, right then, in his soul, internalizing a pathological belief in the power of fate. Taken to a twisted extreme, could such fatalism justify murder? If God wills all, permits—no, guides—death, then even a murder is a natural event; the killer’s hands merely execute that which is predestined to occur.

that his father had died suddenly, and young. Practically speaking, it meant Sukhwinder, little Jodha, already spoiled as the baby and center of attention in a family with means, had no father to discipline him and inject reality into his fantasy world. He was young enough to feel little pain at Fagun’s death, having been told that there was no need to grieve. Fagun had led a successful life. And death is God’s will. Do not grieve. You needn’t feel—anything. More ominously, something peculiar may have taken root, right then, in his soul, internalizing a pathological belief in the power of fate. Taken to a twisted extreme, could such fatalism justify murder? If God wills all, permits—no, guides—death, then even a murder is a natural event; the killer’s hands merely execute that which is predestined to occur.

The family story went that a heart attack felled Fagun. But he hadn’t been sick, had no history of heart problems. “Heart attack” is a euphemism in Punjab for murder. Some in the family were convinced he was killed by enemies. As a police officer, there was no shortage of people whom Fagun may have upset over the years. And payback is an old Indian tradition, especially in the villages. Grievances last generations, revenge is patient. Sometimes it comes in the form of powder slipped into a drink, causing the victim to double over and die in a manner that, in fact, resembles a heart attack. Physicians were known to take bribes in order to declare a murder was in fact death by natural causes.

With Fagun gone, young Sukhwinder, well-fed and mischievous, continued on happily, living on magically inherited wealth. Fagun’s death also killed whatever chance there was that Dhillon would grow up as an orthodox Sikh. Sikhism as a religion is in one sense a rebellion against the old ways of the Hindus, with their hundreds of gods, lavish temples, and rigid caste system that orders people according to their social class. The founding Sikh gurus disdained religious symbols, but ultimately, in order to survive, the “five Ks” were introduced to distinguish Sikh men from others:

Kesh

(the hair must be uncut),

Khanga

(a small comb worn in the hair),

Karra

(steel bracelet),

Kachha

(underwear similar to breeches),

Kirpan

(a small sword, or dagger, about six to nine inches in length, to be used only in self-defense). Sikhism, in its

purest form, promotes one God, as well as equality, respect, dignity, courage. Treat your fellow men, and women, with respect. It is a noble calling, for those who honor the precepts.

Kesh

(the hair must be uncut),

Khanga

(a small comb worn in the hair),

Karra

(steel bracelet),

Kachha

(underwear similar to breeches),

Kirpan

(a small sword, or dagger, about six to nine inches in length, to be used only in self-defense). Sikhism, in its

purest form, promotes one God, as well as equality, respect, dignity, courage. Treat your fellow men, and women, with respect. It is a noble calling, for those who honor the precepts.

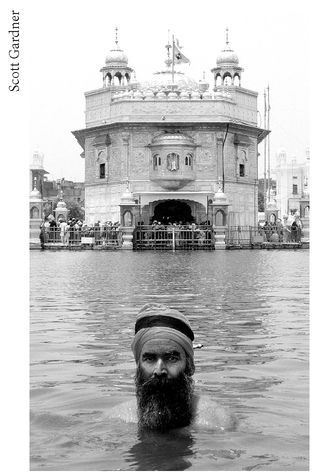

A Sikh man bathes at the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Sukhwinder had been raised as a believing Sikh, just like his brothers Sukhbir and Darshan had, following Fagun, who had worn the turban. As a boy, Sukhwinder wore the thin nylon wrap that fitted the head like a bathing cap. Orthodox Sikh boys wear them, with their uncut hair tied in a small ball underneath. One day, they are permitted to wear the turban, the essential, powerful symbol of a Sikh man’s belief, a sign that he is a warrior of faith. Darshan, the eldest brother, kept the tradition, and his turban. But with Fagun gone, Sukhwinder rebelled, wanted to cut his hair. Gobind gave in to her youngest son.

When it was time for young Sukhwinder to go to school in Ludhiana, his twisted logic hardened like concrete. “Let’s see. We own land, have servants. Why should I have to go to school?” he asked his mother. Her answer was not persuasive. He was the only one of the three brothers who didn’t complete at least an elementary school education. Early on, he discovered the folly of attending school sporadically. Miss a day, then show up the next, and the teacher would give him a spanking. The solution was not to go to school at all—and lie effectively about it. He left his mother in the kitchen in the morning, lunch in hand, then disappeared into the bustle of the street below. He would return at the end of the school day, up the steps, his lunch eaten. How was school? Fine. He was not in class. He was out in the markets,

in a yard, playing, dreaming. The phone rang on many afternoons in the house. Gobind answered.

in a yard, playing, dreaming. The phone rang on many afternoons in the house. Gobind answered.

“Mrs. Dhillon? Where is Sukhwinder today?”

“He’s in school.”

“No, he’s not. He’s not in class. Again.”

Gobind fretted over his behavior, but was unable to change it. She hired a tutor to come to the house and connect with the boy. It didn’t work. The same tutor taught a pretty, pale-faced girl who was one year younger than Sukhwinder. The girl never actually crossed paths with Dhillon back then. Her family lived in the north end of the city as well, where she walked to school five minutes away. Her name was Parvesh Kaur Grewal.

Nothing worked with Sukhwinder. He learned to read and write only a few basic Punjabi words. “Why get so upset at him, Mom?” Sukhbir said. “He’s not going to study anyway. We are

jats

[farmers], we have our land, servants. What is the point of making him go to school?”

jats

[farmers], we have our land, servants. What is the point of making him go to school?”

This was the Sukhwinder Dhillon who left India for Canada in 1981: a young, poorly educated man with inherited wealth who had done no work of his own, had no grounding in the morality and honor of Sikh orthodoxy, and who possessed a dreamy sense of himself and a natural affinity for lying in order to create the life he felt he deserved. It was as though Dhillon’s sense of entitlement to easy wealth was fuelled by a peculiar, childish vanity, under which lay a bedrock of insecurity and rage at his shortcomings. He hungered for attention, any attention, from others. Most tragic of all was his greed. It grew inside Dhillon like a mutating bacteria, fuelling an instinctive, morally vacuous conviction that the end, when it comes to money, justifies the means.

Darshan remained in India. Sukhbir, Gobind’s middle son, had already made it to Canada, and met Sukhwinder and their mother at Pearson Airport in Toronto. They climbed into a car and merged onto the 401, Canada’s busiest highway. It was their first time on a Western road, and it was a different world.

In India, most highways are two-way but narrow affairs with no lane markings, braided with holes and bumps. Cars are a luxury item, almost all of them made domestically. Most are the tiny Marutis or white Ambassadors produced in old British factories now owned and run by Indians, all of them looking like roundish 1960s-era diplomatic vehicles. In addition, trucks, buses, bicycles, auto rickshaws, manual rickshaws, horse-drawn carts, goat herders, pedestrians, women carrying crops and pots on their heads, scooters, and motorcycles pack the roads. Many of the vehicles are overloaded with passengers and goods, as if people were racing for the hills to avoid a looming flood, bringing every possession they have. Driving is based on constant split-second reactions. Signaling is rare. Drivers pass at every opportunity, and when confronted with a bus looming straight ahead, you lean on your horn, forcing the other vehicle to slow down or take a wider berth onto the shoulder, where heat-scorched crumbling asphalt morphs into hardpan dirt. Often the vehicles run three or four abreast. The overwhelming sound is that of horns, which all drivers use constantly, employing them as the eyes and ears of the road.

Other books

Infamous: A Bad Boy Sports Romance Novel by Arabella Abbing

Fever by Amy Meredith

Starship Revenant (The Galactic Wars Book 3) by Tripp Ellis

House of Illusions by Pauline Gedge

Anoche soñé contigo by Lienas, Gemma

Birdie's Book by Jan Bozarth

Desert of the Damned by Nelson Nye

The Elite by Jennifer Banash

Bones and Heart by Katherine Harbour

Starlight in Her Eyes by JoAnn Durgin