The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) (18 page)

Read The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) Online

Authors: Craig L. Symonds

Tags: #PTO, #Naval, #USN, #WWII, #Battle of Midway, #Aviation, #Japan, #USMC, #Imperial Japanese Army, #eBook

But passive command from a distance was unappealing to a man with Yamamoto’s worldview. Though the early victories of the Japanese Navy had made him a national hero and won him many official decorations, he had not yet smelled the smoke of battle or even put himself in harm’s way. He confessed to a friend that the accolades that poured into his headquarters after the first victories left him “intolerably embarrassed.” Moreover, Yamamoto may have had a political objective in mind as well. The historian Hugh Bicheno speculates that Yamamoto went to sea during the Midway campaign so that he could return to Tokyo with a decisive victory in hand and use his elevated prestige to depose Tōjō’s government and open negotiations for an end to the war. Whether or not that was part of his grand strategy, Yamamoto’s gambler’s instinct was evident in every part of the Midway plan. Just as he had contrived the Pearl Harbor strike as a dramatic alternative to the thrust southward the previous fall, so now did he prepare a dramatic alternative to the Naval General Staff’s notion of consolidating Japan’s defense perimeter in the South Pacific and the Aleutians. If there was also a political element in play, that only raised the stakes for this nautical gambler.

24

With the plan fleshed out, Yamamoto sent a representative from his staff to Tokyo on April 2 to present it to the Naval General Staff. The man he sent was Commander Watanabe Yasuji, his logistics officer and frequent

shogi

partner. Watanabe was not only a great admirer of his boss, he had also played an active role in developing the plan and therefore had a proprietary interest in its adoption. Watanabe flew to Tokyo by seaplane and reported to the two-story brick building near the Imperial Palace that housed the Naval General Staff. As he laid out the particulars, it soon became evident that the plan would monopolize virtually all the assets of the Imperial Navy and require the postponement of all other plans, including the move to Port Moresby and the seizure of Fiji-Samoa.

Both Nagano and Rear Admiral Fukudome Shigeru, head of the plans division, remained mute. It was Commander Miyo Tatsukichi, the only naval aviator in the room, who challenged Watanabe. A short, wiry man with gold fillings, he had attended both Eta Jima and the Naval Staff College with Watanabe, and the two men knew each other well. Nevertheless, their exchange grew increasingly tense. Possession of Midway, Miyo argued, would be more of a burden than an asset. Even if the invasion went flawlessly, the atoll’s distance from Japan would make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to sustain. Japan’s logistical capabilities were already stretched to the breaking point, and everything needed to sustain Midway as a Japanese outpost—food, ammunition, and especially oil—would have to be shipped there across an ocean crawling with American submarines. Sufficient tankers needed to carry refined oil from Japan to Midway simply did not exist, and, if they did, how wise was it for Japan to be exporting refined oil—the dearth of which had triggered the war in the first place? Moreover, up to this point in the war, Japan had advanced from one position to another only under the umbrella of land-based air. That would not be the case with Midway. The atoll was, however, under the umbrella of American land-based air from Oahu, which would make it vulnerable to American raids and recapture. Finally, if Combined Fleet wanted a battle with the American carriers, one could be had by attacking Fiji or Samoa, the loss of which would break the American link to Australia. And a battle in the South Pacific would give Japan all the advantages that the Americans would have at Midway.

25

Watanabe was not used to hearing such sharp and direct criticism of a plan generated by the commander in chief. He responded to Miyo by asserting that “after capture [Midway] would be supplied the same as was already being done with Wake.” And he pledged “to go to Fiji and Samoa after the Battle of Midway had been won.” Apparently flustered, he merely repeated the outlines of the plan that he had been entrusted to deliver. It was evident that the evidence weighed heavily against adoption of the Midway plan, but Yamamoto’s influence had grown so great that it could not be dismissed outright. Fukudome, who had once been Yamamoto’s chief of staff, tried to calm the heated discussion: “Come, come,” he said, “don’t get too excited. Since the Combined Fleet’s so set on the plan, why don’t we study it to see if we can’t accept it?”

26

The group met again three days later. It was clear at once that studying the details of the plan had only confirmed Miyo’s doubts. He reiterated, even more strongly, its obvious defects. Unable to counter Miyo’s arguments, Watanabe left the room to telephone the flagship

Yamato

. He summarized Miyo’s criticisms and asked for a response. Was Yamamoto still committed to the Midway plan? He was. Watanabe returned to the room to tell the members of the General Staff that Yamamoto’s mind was made up, and that “if his plan was not adopted he

might

resign.”

It was Fukudome who asked the crucial question: “If the C in C’s so set on it, shall we leave it to him?” No one else in the room spoke, but several nodded. Nagano capitulated once again, as he had over the Pearl Harbor raid. Miyo could only bow his head; some thought he was forcing back tears. Yamamoto had forced the Pearl Harbor raid onto the General Staff by bluff and threat. Now he was imposing the Midway plan on his skeptical and reluctant superiors. The behavior of the Naval General Staff was, as the historian H. P. Willmott has noted, “nothing less than an abject and craven shirking of responsibility.”

27

The Army’s response was, in effect, a shrug. Since the plan did not call for any significant participation by the Army, its leaders seemed to say: do whatever you want so long as you don’t call on us for support. But the Army did worry about Inoue’s move southward to Port Moresby, for that did involve Army assets, and as a result, five days after winning his victory over the Naval General Staff, Yamamoto agreed to lend one carrier division of the Kidō Butai to Inoue for what was codenamed Operation MO—the capture of Port Moresby. For that operation, Yamamoto selected the newest and least experienced of the carrier divisions—CarDiv 5, composed of the new carriers

Shōkaku

and

Zuikaku

. Inoue had to promise that he would complete the conquest of Port Moresby swiftly, so that those carriers could rejoin the Kidō Butai in time for the Midway campaign, now codenamed Operation MI. The Fiji-Samoa operation would have to be postponed until July, though Yamamoto agreed to allow a smaller operation for the capture of Ocean and Nauru Islands (Operation RY), and another to seize the westernmost islands in the Aleutians (Operation AL). This latter effort, often referred to as a diversion for Midway, was in fact a separate initiative unrelated to the Midway Operation apart from its timing. In effect, instead of choosing between moves to the south, north, or west, the Japanese decided to undertake all three, and to do so virtually simultaneously.

28

In addition to internal military politics, one reason for the apparent hurry was that both Yamamoto and the Naval General Staff recognized that Japan’s carrier superiority in the Pacific was only temporary. The Japanese had six big carriers to the Americans’ three (or perhaps four—they weren’t sure where the

Wasp

was), but they knew that the Americans had no fewer than eleven big carriers under construction, all of which would become operational in 1943; the Japanese had only one under construction, the

Taihō

, which would not be available until 1944 (though they also converted several other existing ships into carriers). In short, the Japanese needed to complete their conquests and establish their defensive perimeter before the new American carriers and the flood of American airplanes began arriving in the Pacific.

The day after the Naval General Staff capitulated to Yamamoto’s Midway Operation, the planes of the Kidō Butai conducted their raid on Colombo in far-off Ceylon and sank the

Dorsetshire

and

Cornwall

. Four days later they struck at Trincomalee and sank the

Hermes

. Soon they would be returning through the Straits of Malacca to the Pacific. They would need to refit and resupply, and then they would be ready for more operations. The officers and men were hoping for liberty in Hiroshima. They would be disappointed. The crews of the

Shōkaku

and

Zuikaku

would not even be allowed to reach a Japanese port. Instead, those two ships underwent a quick resupply in Formosa so they could be ready for Operation MO.

On April 16, Nagano presented the “Imperial Navy Operational Plan for Stage Two of the Great East Asia War” to Emperor Hirohito, who, in theory at least, had final approval of all operations. Plans were never presented to the emperor until all the competing elements in the military and the government had agreed; all Hirohito could do was bless a decision that had already been made. The chief of the Army General Staff was present when Admiral Nagano presented the outlines of the Midway plan. He silently acquiesced because it did not call for the allocation of any soldiers. The landings and occupation of Midway would be the responsibility of Naval Infantry—the Japanese version of Marines. The Army may have suspected that Yamamoto’s plan was only the first step toward an invasion of Hawaii, which certainly would require support from the Army, but it could speak up in opposition to that move when the time came.

29

Yamamoto had won, though it was not yet clear what the consequences of his internal victory over the Naval General Staff and the Army might be. As Commander Miyo had pointed out, the thrust into the Central Pacific was a gamble even if the Kidō Butai triumphed over the American carriers, for the logistical burden of sustaining an outpost at Midway, 2,235 nautical miles from Tokyo, was daunting, especially if the Army continued to remain on the sidelines. On April 16, the day when Nagano presented the plan to the emperor, it was hard for Army leaders to imagine a set of circumstances that would cause them to change their mind about supporting this adventure in the central Pacific.

Two days later, American bombers appeared over Tokyo.

*

Early in 1941, Yamamoto wrote a letter to another officer who favored war with America. In that letter, Yamamoto stated that in any such war the Japanese would be compelled to seek “a capitulation at the White House, in Washington itself.” After the war began, Japanese newspapers published this letter, which led the Western press to assume that this was, in fact, Yamamoto’s goal. Instead, Yamamoto had written the letter as a way of suggesting that a war with the U.S. was not winnable. The next line in this letter, omitted when it was published, was: “I wonder whether the politicians of the day really have the willingness to make [the] sacrifice … that this would entail.”

6

Pete and Jimmy

T

he wild card in America’s carrier force was the USS

Hornet

, a sister ship of the

Yorktown

and

Enterprise

with essentially the same characteristics and capacity. Commissioned in October, six weeks before Pearl Harbor, she remained in Norfolk over the winter as she fitted out, and it was not until March of 1942 that she was ready for sea with a crew, an air group, and a commanding officer. That commanding officer was Captain Marc A. Mitscher, whose Academy nickname was “Pete.” The nickname came about because Mitscher had arrived in Annapolis from Oklahoma in 1904 soon after another Oklahoma native named Pete Cade had “bilged out.” Cade had been a popular mid, and his classmates were unsure that trading him for the short, skinny, and taciturn Mitscher was a good bargain. They ordered the new plebe to call out the name of the departed Cade every time an upperclassman required it. On those occasions, Mitscher would brace up and shout out: “Peter Cassius Marcellus Cade, Jr.” His classmates took to calling him “Oklahoma Pete,” and Pete he remained for the rest of his life.

1

For some time it looked as if the new Pete would follow the same course as the old one at Annapolis. Mitscher got bad grades and lots of demerits. For two years, he was constantly on the brink of being kicked out. And then he was; in 1906, at the end of his second year, he was ordered to resign. In an act of defiance, he wrote out his resignation on a piece of toilet paper. In spite of that, and perhaps as a sop to the congressman who had appointed him (a friend of Mitscher’s father), he was allowed to reenter the Academy, but only if he started over as a plebe. Out of either stubbornness or determination, or perhaps both, Mitscher reentered the Academy as a member of the class of 1910. Though he was repeating classes he had already taken, his grades remained poor, and his conduct worse. Nor was he especially popular. He seldom laughed or even smiled, and his natural quietness was interpreted by some as sullenness. His odd looks did not help. Short and slight, he had milk-white skin that burned easily, and white, wispy hair that was already thinning noticeably, which he combed over the top of his balding head. The 1910

Lucky Bag

profiled him in verse:

Pete dislikes all allusions or mirth

On the hue of his hair or its dearth

It gives him much pain

When he has to explain

That he’s not an albino by birth.

He spent a lot of his time smoking and card playing, and several times came close to being expelled again. He graduated third from the bottom of his class in 1910, after six years at Annapolis.

2

Mitscher’s early career as a surface officer was as undistinguished as his record at the Academy. Despite his diminutive size, he was stubborn, argumentative, and short-tempered, and he managed to get into a surprising number of fights. Then in 1915 his career changed dramatically when as a lieutenant junior grade he was accepted into the new Bureau of Aeronautics. Mitscher decided it was an activity that was worth his time and effort—for one thing, his diminutive stature was actually an asset in an airplane’s cockpit. The card-playing slacker became a hard worker and an enthusiastic devotee of aviation. Moreover, as one of the first students to show up at Pensacola in the Navy’s infant flying corps, Mitscher got in on the ground floor of a new service that was soon to expand rapidly. In June of1916, at the age of 29, Pete Mitscher became Naval Aviator Number 33.

3

At that time, of course, there were as yet no aircraft carriers in the U.S. Navy (the

Jupiter

would not be converted into the

Langley

until 1920). For four years, Mitscher flew fabric-covered seaplanes resembling box kites from shore bases; only occasionally were they propelled off the back of cruisers. Breakdowns were frequent, and the pilots patched up their own cloth-and-string “aeroplanes” after each crash, of which there were many. One authority estimates that for every fifteen minutes of flying time, the pilots spent four hours making repairs. The newly promoted Lieutenant Mitscher described what may have been a typical day in a letter home to his wife, Frances: “We transferred ten wrecks to the yard, and repaired two. The other day Donohue smashed one of the remaining ten and we worked night and day to get it ready. Stone fired off with it today and smashed it again, so we now have to repair some more.”

4

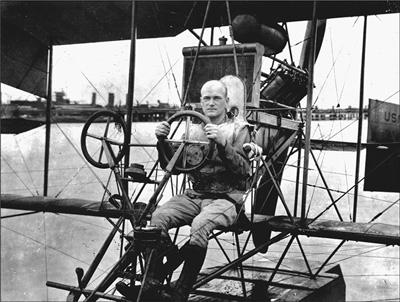

Lieutenant “Pete” Mitscher at the controls of an early seaplane in Pensacola, Florida. Becoming a pilot completely changed the trajectory of Mitscher’s naval career. (U.S. Naval Institute)

Lieutenant “Pete” Mitscher at the controls of an early seaplane in Pensacola, Florida. Becoming a pilot completely changed the trajectory of Mitscher’s naval career. (U.S. Naval Institute)

To his great disgust, Mitscher did not see any action during World War I. Instead, his big break came after the war, in 1919, when he was assigned to join the Navy team that attempted the first transatlantic crossing by air. Rather than make the flight in a single hop, the plan was to fly huge seaplanes—essentially flying boats, designed by Glenn Curtiss—from the American east coast to the Azores and then on to Europe. Mitscher was a backup pilot on the NC-1 (N for Navy; C for Curtiss). Though only one of the three planes (not Mitscher’s) managed to complete the trip, the exploit brought the Navy plenty of positive publicity, and Mitscher and everyone else involved received the Navy Cross.

5

Mitscher’s early involvement in naval aviation proved the making of him. In 1925, President Coolidge asked his friend Dwight Morrow to head a board to evaluate the potential of aviation for the services.

*

Called to testify before the Morrow Board, Mitscher declared that it was entirely inappropriate for black shoe officers to have management of pilots and airplanes. He asserted that only “experienced aviation men should have administration of the training of aviation personnel and the detail of aviation personnel.” While this was entirely logical and genuinely reflected Mitscher’s views, it also helped ensure that those who had managed to get into the game early would have the first claim on supervisory positions when naval aviation became a major component of the fleet.

6

Mitscher wrote privately that it was “the great ambition of [his] life” to get on board “an aviation ship,” which he finally did in 1926. A year later he was the air boss on the new

Saratoga

. Two years after that he was the exec on the

Lexington

. He was not interested in grand strategy and never attended a war college. A fellow officer described him as “a person who did not enjoy the long process of planning, of thinking too much about logistics.” He just wanted to fly, and he was good at it. One problem was that his fair skin made the outdoors into a hostile environment. He burned so easily that despite wearing a specially designed long-billed baseball cap, his nose was always peeling. Eventually his sun-ravaged skin gave him the look of a withered gnome. He remained both stubborn and temperamental, though he no longer got into fistfights. He also remained taciturn, and when he did speak it was in a voice so low that others were compelled to lean in close to hear him. A fellow officer recalled that he was “very, very quiet and seldom said much,” and another that “he never used five words if one would do.” Despite his low voice, he disliked having to repeat things and fired a staff officer who asked him to repeat himself once too often. By 1938 Mitscher had become a Navy captain and the assistant chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Then in May of 1941 he was selected as the prospective commanding officer of the new-construction

Hornet

. Many of his Academy classmates were astonished.

7

As captain of the

Hornet

, Mitscher no longer flew airplanes, and he missed it. He remained reticent, seldom telling jokes or engaging in light banter. He spent hours in his cabin chain-smoking and reading paperback detective novels. “He would go through a novel in nothing flat,” a shipmate recalled. Despite that, Mitscher exuded an air of confidence and authority, especially when it came to air operations. He realized that he had a green crew—fully 75 percent of the men on board the

Hornet

were fresh from boot camp or cadet training—and he patiently tried to bring them up to the mark. The 18-year-old helmsman on the

Hornet

thought the soft-spoken skipper “gave the impression of being a kind, gentle, and highly intelligent person.” But Mitscher’s patience was often tested, especially when it came to air operations, and he showed occasional flashes of anger, particularly toward his young pilots. During the

Hornet’s

shakedown cruise, while watching flight operations from the open bridge wing, he saw the landing signal officer wave off Ensign Roy Gee during his first approach. Gee came around again and worked his way back into the pattern, but as he made his approach the LSO waved him off again. It took Gee ten tries before the LSO finally gave him the cut sign and Gee landed safely. When he climbed out of his airplane, he was ordered to report at once to the bridge. There he was confronted by an irate Mitscher.

“Can’t you fly?” Mitscher asked.

“I won’t do it again, Captain,” the humiliated ensign replied.

“You’re damned right you won’t,” Mitscher told him. “You’re not ever going to fly off this ship again.” Mitscher ordered that Gee’s name be struck from the flight roster. But if Mitscher was quick to anger, he also relented quickly. Five days later he ordered Gee restored to flight status.

8

On the last day of January 1942, the

Hornet

was anchored off Norfolk when Captain Donald “Wu” Duncan, Ernie King’s air officer, came on board. Once he was alone with Mitscher, Duncan asked him a question: “Can you put a loaded B-25 in the air on a normal deck run?” That depended, of course, on how many planes crowded the flight deck. Mitscher thought a moment. “How many B-25s?” he asked. “Fifteen,” Duncan told him. Mitscher bent over the spotting board, a wooden template of the

Hornet

’s flight deck that showed where each plane was placed at any given moment. He calculated how much space a B-25 with its 67-foot wingspan would take up on the

Hornet

’s deck. Finally he answered that it could be done. “Good,” Duncan replied. “I’m putting two aboard for a test launching tomorrow.”

9

The big land-based, two-engine Mitchell bombers had been named for Billy Mitchell, the interwar U.S. Army general who had been court-martialed for accusing Army and Navy leaders of “criminal negligence” for not making a greater commitment to air power. The Mitchell bombers were about the size of a Japanese Nell and, in conformance with Mitchell’s vision, had been designed for coastal defense. They were too big to land on a carrier and had to be hoisted aboard the

Hornet

by crane at the Norfolk docks. On February 2 (two days after Fletcher and Halsey struck at the Marshalls in the Pacific), the

Hornet

went out into the Atlantic with two Mitchell B-25s lashed to her flight deck. At 53 feet long and with that 67-foot wingspan, the two planes looked out of place even on the broad deck of the

Hornet

. The weather was less than ideal—a light snow was falling—and the test was interrupted when one of the escort vessels reported what was believed to be the periscope of a submarine, which proved instead to be the tip of a mast on an uncharted wreck. In the end both planes took off safely and without incident, flown by young Army pilots with no previous training in carrier operations. Duncan was satisfied. He left the next day to take the news back to Washington, where several very senior officers were waiting.

10

*